Received wisdom has it that Chairman Mao did nothing for the progress of Chinese culture. Those who would advance this claim must account for the singular career of the animator Te Wei (22 August 1915–4 February 2010). For it was under Mao that Te laid down the fundaments of a national animation style, and produced some of the most ravishing films ever made in the country.

A paradox of totalitarian regimes is that, even as they set limits on what can be expressed in art, they can give the artist considerable freedom within those limits by mobilising public funds and removing the pressures of the market. In Soviet Russia, the likes of Andrei Tarkovsky and Yuri Norstein drew on state largesse to make stunning films that were both hugely costly and resolutely uncommercial. The Communist Party of China was not as generous, but without its patronage we likely wouldn’t have witnessed the extraordinary creative activity that centred on the Shanghai Animation Film Studio (SAFS) from the 1950s onwards.

The state made Te Wei an animator, and bankrolled the best part of his work. But it also issued directives for what would become the great aesthetic project of his career: no less than the invention of a uniquely Chinese style of animation. As the head of SAFS, Te encouraged his colleagues to experiment with centuries-old artistic traditions. In his own films he focused on adapting watercolour paintings to animation, in the process developing techniques that still baffle animators today.

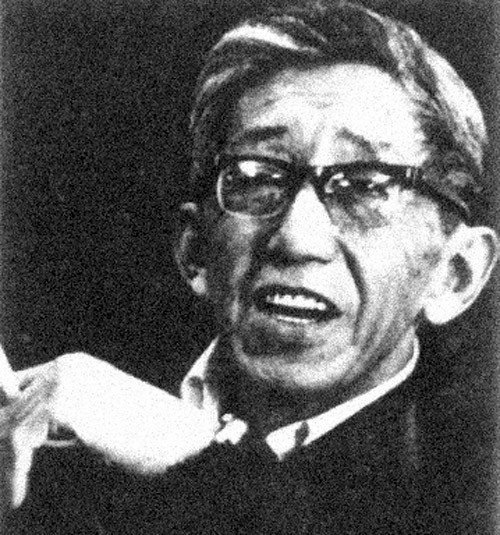

Te Wei

The career of this most Chinese of animators did not start auspiciously. Born one hundred years ago to a poor family in Shanghai, Te Wei began to draw political cartoons in his late teens, which he sold to the city’s many internationally-oriented magazines. Indeed, his strips owed much to Western comics, with their caricatural style and accurate perspective. He eked out a living by joining a collective of cartoonists who produced anti-Japanese propaganda, though Japan’s encroachment into the continent obliged him to flee to the relative safety of Chongqing, where he settled in 1940. There, under the relatively liberal Kuomintang government – which was simultaneously fighting the Japanese and the Communists – he spent a quiet decade painting mostly in water and ink.

In 1949 Mao’s Communists rode victorious into Beijing, and set about creating a vast state-backed culture industry. Over at the Changchun Film Studio, an executive who fondly remembered Te’s anti-Japanese cartoons summoned him to head her animation division, despite his total lack of experience in the medium. “But it was an order, and I had to do this job,” he would later reflect. Ironically, he learned his craft under a brilliant Japanese animator named Tadahito Mochinaga (later a pioneer of stop-motion film in his motherland), with whom he would remain friends for life.

Within a year the department had relocated to Shanghai, and in the ensuing decade its ranks swelled with young talent. By the time it was established as the independent Shanghai Animation Film Studio in 1957, it received lavish subsidies and boasted a 200-strong staff who produced some 15 films (mostly shorts) annually. Taking advantage of the brief window of artistic freedom opened by Mao’s Hundred Flowers Campaign, its animators experimented with form and technique, and began to introduce native traditions to their work.

It is in this climate that Te directed his first short. The Proud General (aka The Conceited General, 1956) tells the tale of a military commander who’s so smug about his recent victory that he fails to anticipate the next battle. While taking a potshot at feudal warlordism (one of the Communist Party’s favourite targets), the film packs in plenty of comic incidents for kids, which the government considered to be the only audience for cartoons. Like many productions of the time, the animation – thick outlines, block colours – is indebted to Western and Soviet animators, notably Walt Disney and Ivan Ivanov-Vano. But there are shades of a nascent home style in the background art, and the scenes inspired by Peking Opera mark a new departure.

During production, another SAFS film – Why Crows Are Black (1956), supervised by the pioneering Wan Brothers – took a prize at the Venice Film Festival. But to China’s embarrassment, it was mistaken for a Soviet film.

Two decades earlier, the Wan Brothers had written a manifesto of sorts in which they praised foreign animation, but stressed the need to develop a uniquely Chinese aesthetic. Now the government began to impress this objective on the studio, and the following years saw a profusion of films that incorporated traditional techniques, such as paper-cutting (the Wans’ Pigsy Eats Watermelon / Zhu Bajie Eats Watermelons, 1958 [►]) and paper-folding (Yu Zhenguang’s A Clever Duckling / The Clever Ducklings, 1960 [►]). Others reimagined Chinese folk stories, or depicted recent historical events (usually at the expense of the Kuomintang, natch).

On a visit to the studio, Vice Premier Chen Yi set Te a challenge. Qi Baishi, one of China’s most popular artists, had recently died, and Chen wanted the studio to produce an animated version of his delicate ink paintings. Te assembled a crack team of visionary animators – including his future friend in exile A Da – and set to work producing his first great work.

Qi was a master of watercolours, a brilliant landscape painter and a leading exponent of the self-explanatory bird-and-flower school of painting. But in his later years he broke with precedent by focusing on shrimps and other water creatures, and it is to this aquatic milieu that Te turned for Where Is Mama? (aka Tadpoles Look For Mother, 1960). The plot is mild agitprop allegory: a group of tadpoles have been separated from their mother, and are looking for her. Points are duly made about the importance of civic cooperation and state protection, as the chirpy voiceover reminds us that all plants need to be guarded against ‘pests’ (in truth, this is one of the few films that benefits from the mute button).

What is remarkable about the film is that, on attempt number one, Te and his team have emulated the exquisitely graded ink-and-water style to perfection. Gone are the bold outlines and primary colours; indeed, as Swiss animator Georges Schwizgebel, who was friends with Te, put it to me, Te’s great achievement is to animate the characters such that they seem to be of a piece with the backgrounds. The assorted fish and birds that the tadpoles encounter on their journey are beautifully rendered in diffused watercolours. How their outlines stay stable as they move remains something of a mystery in animation circles.

Where Is Mama? picked up several prizes in China (though it would not be seen abroad for decades). Flushed with success, Te pressed on with his next short. In The Cowboy’s Flute (1963), a young boy takes his buffalo for a walk in the hills. Stopping for a nap, the boy dreams that his animal wanders off into the wild, and that he has to summon him by playing a ditty on his flute. Once again, Qi’s influence is in evidence, as is that of renowned landscape artist Li Keran. The boy has a Disney look to him, but the backgrounds are drawn with a characteristically Chinese sparseness, verging on abstraction in places. As in Where Is Mama?, the story follows a simple but resonant arc of separation and reconciliation.

The Cowboy’s Flute was every bit as sumptuous as its predecessor, but by now the national mood had changed. The permissiveness of the Hundred Flowers years was over, and the film was attack for “failing to reflect the class struggle and numbing the consciousness of the public”. As Mao geared up for his Cultural Revolution, the studio was shut down in 1964, and Te was interned in solitary confinement. For a year, he was beaten, deprived of sleep and obliged to pen self-criticisms. He later recounted how his room had a table with a pane of glass in it; he would keep himself sane by drawing sketches on it, which he would erase when he heard the guards approaching.

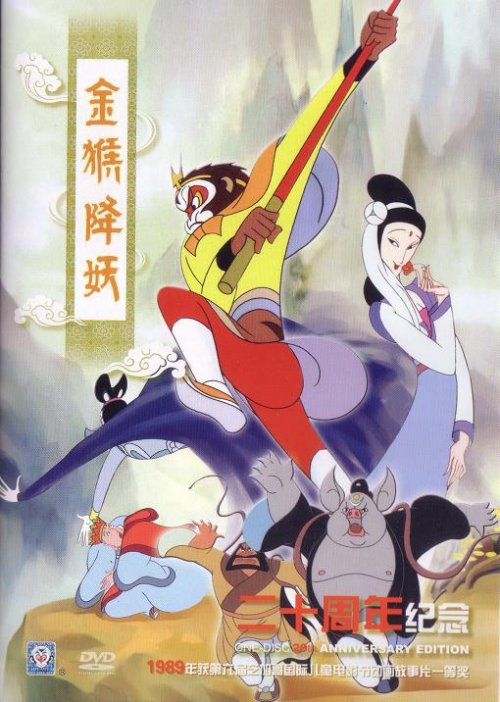

A DVD cover for Monkey King Conquers the Demon (1985)

Te passed the following years exiled in the countryside, some of which he spent raising pigs with A Da. Only in 1975 was he invited back to the studio, initially as the librarian, and subsequently to direct a propaganda film about Tibet. Gradually the strictures of the Cultural Revolution were lifted and the old staff came back; Mao’s death and the downfall of his acolytes soon after paved the way for an artistic renaissance. Far from revolutionising anything, the surreal policies of Mao’s last years had only plugged the creative flow, such that in the late 70s the studio’s animators returned to their drawing boards with the same vision and a renewed energy.

Te later described the 80s as the most intense period of his career. Under his stewardship the revived studio expanded its staff to 500, and made use of new technology and fresh talent to produce some of its best and most experimental work to date – see A Da’s quirky Three Monks [►], or Jingqing Hu’s Snipe and Clam Grapple [►] (which is clearly influenced by Where Is Mama?). Crucially, SAFS still had the luxury of state funding. “The studio looked nothing like the cramped animation factories that I later visited in Taiwan,” says Schwizgebel of his visit in 1984. “Production was fairly slow and time wasn’t of the essence.”

After stepping down as president in that year, Te hung around to direct two more films: the enjoyable if commercial Monkey King Conquers the Demon (1985), a feature adaptation of the Chinese epic novel Journey to the West, and Feelings from Mountain and Water (1988). This last effort is his masterpiece: a supremely accomplished recapitulation of the various themes and motifs that had preoccupied him throughout his career, tinted with a new melancholy.

The title refers to the landscapes of the shan shui (literally, ‘mountain and water’) school, which serve as the inspiration here as in The Cowboy’s Flute. But Te’s palette has taken a turn for the monochrome. More prominence is given now to empty space in the frame, and to silence on the soundtrack: for minutes at a stretch, we only hear wind. The story, about an ailing scholar who gives zither lessons to a young girl in return for domestic care, suggests an artist ready to pass his mantle on to the next generation.

Did Te intend Feelings to be his last film? Certainly, he spoke in later years of looking for a script to direct; but in any case, the market forces unleashed by Mao’s successor Deng Xiaoping were rapidly changing the rules of the game. Even as SAFS’s films began to find an appreciate audience abroad, the grants that had allowed them to be made were being slashed, and the industry was beginning to haemorrhage talent to the recently arrived American and Japanese companies. New Chinese studios were set up to provide cheap outsourced labour for foreign projects. The priority was no longer artistic achievement but productive capacity, and financing for films like Te’s dried up.

Te Wei in 2006, four years before his death at the age of 94

Credit: Marie-Claire Kuo / Centre de Documentation sur le Cinèma Chinois, Paris

In 1989, Te was singled out by the Communist Party as one of the four outstanding filmmakers in the nation’s history. It was a fitting apotheosis from a government that had given him so much support and dealt him so much pain. Yet the artist who had survived the Cultural Revolution did not weather the transition to the market economy, and he did not work in the last two decades of his life.

Today, the Chinese animation industry is highly productive, especially in the television sector. Yet in contrast to the country’s live-action cinema and contemporary art, works of artistic merit are few and far between. SAFS continues to score the occasional success, but it seems as concerned with its past as with its future: in 2013, it filed a lawsuit against Apple, accusing the company of illegally uploading its films to the iTunes Store. Similarly, the government has awkwardly instituted a range of protectionist measures to stem the influx of foreign cartoons, while failing to maintain its programme to develop an indigenous animation style. Promising work, notably in Flash animation and within the country’s specialist schools, hints at the untapped reserves of creative talent in the country. Will the state find a way to harness it, as it did before?

Further reading

Electric Shadows: A Century of Chinese Cinema

An introduction to the long and illustrious history of Chinese cinema, from the earliest silent films through the glamour and invention of Shanghai’s golden age in the 1930s, from the restrictions of the Cultural Revolution to the grand renaissance of the Fifth Generation directors in the 1980s, and from the underground, independent spirit of the 1990s to the booming multiplex cinema of the present.

Includes A Brief History of Chinese Animation by Li Zhen.

Contributors include Chris Berry, Michael Berry, Peggy Chiao, Tony Rayns, Bérénice Reynaud, Yingjin Zhang, and filmmakers Tsui Hark, Jia Zhangke, Ann Hui, Feng Xiaogang and Stanley Kwan.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.