“It was the idea that you have to try to love in another way, to continue, to develop a relationship.”

— Anne-Marie Miéville

Anne-Marie Miéville is a hugely important multimedia artist. She is a filmmaker, editor, writer and photographer whose presence continues to define one of the most productive, giving and enduring collaborations in cinema. She has written and directed four short films and four feature films, which separately and together reveal a pervasive fascination with the complexity of human relationships. Her cinematic production is insistent, undaunted and keenly perceptive and her films demonstrate a great aptitude for creating unnerving moments of tension while offering audio-visual experiences that are amusing, quirky and deeply moving. Miéville’s sustained concern with sexual difference, the couple, family relations, loneliness and the everyday are accompanied by a striking attentiveness to the emotional power of music and bodily expression. Anne-Marie Miéville is anything but Jean-Luc Godard’s quiet companion. Indeed, it is her intense interest in communication, its possibility and its failure, that has shaped and continually reignited the long-lasting bond between them.

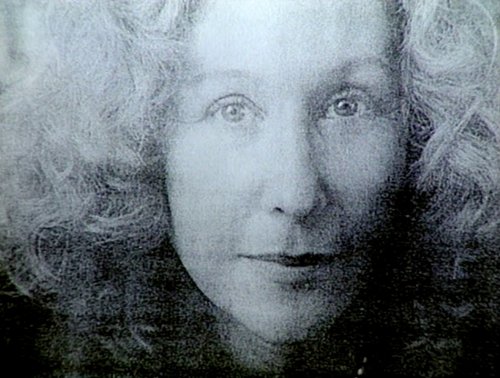

Miéville as depicted in Jean-Luc Godard’s Histoire(s) du Cinéma (1998)

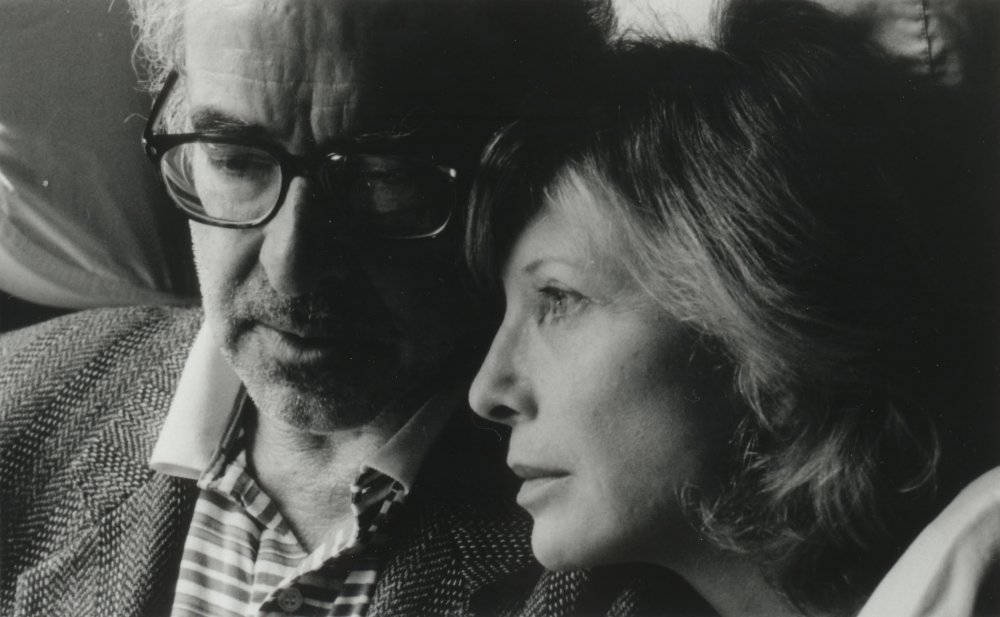

According to Richard Brody [Everything is Cinema: the Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard], Godard and Miéville first met at the Cinémathèque Suisse in 1970. At this time, Miéville was a photographer living in Paris and working at a pro-Palestinian bookshop. She had a young daughter and she often travelled back and forth between France and Switzerland to visit her family. Colin MacCabe [Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at Seventy] has revealed that following Godard’s near-fatal motorbike accident in 1971, Miéville became a constant support to Godard and their relationship grew stronger. She initially worked alongside her brother as the stills photographer on Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin’s Tout va bien (1972) and went on to form the solid and affectionate artistic partnership with Godard that has continued for more than four decades and is still going to this day.

Together, Miéville and Godard have produced an extraordinary body of work that embraces new technology while reflecting critically on it. Through the innovative experiments they carried out during the 1970s with video and television, they invented alternative forms of thinking via the organisation of images and sounds. In so doing, Miéville-Godard laid the foundations for some of the key ideas that they would go on to develop, separately and together, in the decades that followed.

After the Reconciliation (Après la reconciliation, 2000)

The Miéville-Godard collaboration officially began in 1973 when Godard created the Sonimage studio in Paris and when Miéville was made the company’s legal representative. Soon afterwards Miéville and Godard re-located to Grenoble and it was here that they conducted some of their pioneering research into video technology, tape-speed alteration and slow-motion. Setting up their own production company (likewise called Sonimage – literally ‘Soundimage’), and unhooking themselves from the pull of the French capital, Miéville and Godard found a way of working freely and autonomously in a self-sustaining environment outside the mainstream film industry. Together, they set up what was in effect a workshop of sounds and images, purchasing televisions, monitors, cameras and a photocopier to experiment with.

The decentralisation of film production and their interest in alternative distribution, initiated by their move to south-eastern France, was intensified further following a second and more radical move in 1977 to Rolle, a small town in Vaud, Switzerland, the canton where both Miéville and Godard grew up. Re-locating the Sonimage studies here on the shore of Lake Geneva created the perfect space in which Miéville and Godard could take the time to develop their own unique working rhythm, fashioning in the process a collaborative practice and a way of life that developed instinctively and spontaneously from the fusion of work and love.

Michael Witt [For Ever Godard; Jean-Luc Godard, Cinema Historian] has written extensively about their collaboration during the 1970s, which strove “to live out a working practice in which the divisions of labour and of the sexes were dissolved in a reflection on the implications of finding pleasure in one’s work whilst collaborating with a partner one loves (to love work, and work at love)”. This has remained an important and reoccurring theme in the films that Miéville and Godard have made together and as solo artists.

Soft and Hard – A Soft Talk on a Hard Subject Between Two Friends (1985)

Significantly, Miéville played a crucial role in steering the Sonimage films away from the rigid political framework that marked Godard’s prior collaborations with the Dziga Vertov Group. Instead, Sonimage was most concerned with the politics of personal experience and everyday life. Until the production company’s official dissolution in 1981, Miéville-Godard produced a vast amount of material, incorporating the findings of their formal experiments with video, and gradually bringing to fruition another way of working with dialogue, gesture, speed and sound that would greatly influence their subsequent commercial feature films.

Miéville-Godard were discovering methods of relating to each other differently, relating to sounds and images differently and relating to the world differently. In a sense, what the Sonimage studio had been doing all along was asking the spectator to participate in the filmmakers’ displaced and co-creative dialogue, by searching with them for a different manner of seeing, thinking, listening and responding to the organisation of images and sounds.

The Miéville-Godard films produced by Sonimage between 1973 and 1979 were Ici et ailleurs (Here and Elsewhere, 1975), Numéro deux (1975), Comment ça va? (1976) and the two trailblazing television series, 6 x 2 Sur et sous la communication (1976) and France tour détour deux enfants (1979). Most importantly, Miéville co-wrote Numéro deux and worked as co-author, co-director and co-editor on all of the remaining Sonimage films that they made together at this time.

Ici et ailleurs (Here and Elsewhere, 1975)

Sonimage’s first film, Ici et ailleurs, dubbed “the blueprint” of Histoire(s) du cinéma by Witt, is a fascinating work that mixes video with 16mm film and investigates the damaging effects of television on cinema and society through a soft voiceover dialogue between a woman (Miéville) and a man (Godard). The film contains fragments of the rushes shot by Godard and Gorin in 1969-70 for their unfinished project Jusqu’à la victoire, which Miéville and Godard spent a devoted but gruelling period editing and reworking.

The sequences in Ici et ailleurs showing a French family ‘here’ (ici) at home, eating a meal, watching television, arguing, or doing homework, underline the importance for Miéville-Godard of the local, the personal and the everyday and the role these factors play in our understanding of political and human conflict ‘elsewhere’ (ailleurs). Yet it is most of all through the auditory presence of Miéville’s discerning voice, which unravels and critiques dominant modes of representation and challenges the ethics of Godard’s own directorial choices, that her influence is felt.

Numéro deux is set on a housing estate and it deals with a different set of themes. The focus is now on sexuality, cinema, politics, the family unit, domestic space, violence and oppression. Looking back at this film through the lens of Miéville-Godard’s later video essay Soft and Hard (made for Channel 4 television, 1985) we are reminded of Miéville’s early fascination with cinema. In Soft and Hard, during a lengthy conversation with Godard, she fondly remembers how as a child she used to project her family’s photographs on to her bedroom wall. This particular memory was recalled by Godard in a joint interview given with Miéville at the time of the release of her latest film, After the Reconciliation (2000). He keenly reminds us that her childhood interest in projection and light pre-dated his own.

Numéro Deux (1975)

It is also significant that certain poignant scenes in Numéro deux resonate powerfully with moments in Miéville’s own later work. For example, the sequence of Sandrine and her daughter dancing around the kitchen in their dressing-gowns to a revolutionary song and the shots of Sandrine and her partner Pierre fighting foresee similarly charged moments between Marie and her parents in The Book of Mary (1985) and between Lou and Pierre in Lou n’a pas dit non (1994).

The potency and ubiquity of music and dance in Miéville’s post-Sonimage films can be read in relation to films such as Numéro deux, Six fois deux and France tour détour deux enfants because these three works include an important and eruptive musical dimension. France tour détour deux enfants is both a television series and a subversive audio-visual choreography, composed not of episodes but of ‘movements’.

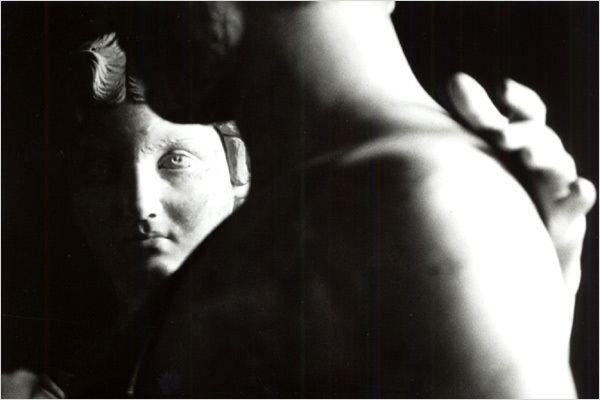

The combination of music, altered motion and the everyday gestures of two children look ahead not only to Marie’s vivid and almost sculptural dance (to Mahler’s Ninth Symphony) in The Book of Mary but also to Miéville’s stunning cinematic choreography in the sumptuous, Rilke-inspired Lou n’a pas dit non, a study of different couples loving and transforming at different speeds. In this film, the masterful transitions that Miéville creates between shots of the statues in the Louvre (first stationary and later ‘in motion’ as part of Lou’s film), the impassioned dancers on stage and the world of the contemporary couple seem haunted by Miéville-Godard’s early experiments with videographic altered-motion and by the Rodin-inspired love scenes in Prénom Carmen (1983), for which Miéville wrote the screenplay.

Lou n’a pas dit non (Lou Didn ’t Say No, 1994)

Since the Sonimage years, Miéville has continued to collaborate extensively with Godard on films and projects. She co-wrote and co-edited the pivotal feature Sauve qui peut (la vie) (1979), which marked a new point of departure for Miéville-Godard as their attention turned to art cinema – with their entire working method, separately and together, now indelibly marked by their newfound appreciation of the creative potential of the electronic medium of video.

Miéville was also involved in the making of Scénario du film Passion (1983), co-edited Hail Mary (1985), originally screened alongside Miéville’s The Book of Mary in cinemas, and co-wrote Détective (1985). She also co-produced the video work Le dernier mot (1988) and worked as art director on Nouvelle vague (1990) and Notre musique (2004), collaborating too on Film socialisme (2010).

This in addition to Miéville-Godard’s post-Sonimage collaborations, which include the aforementioend Soft and Hard, a poetic video essay that Catherine Grant has aptly called “their own ‘home-movie’” and which closes with a sequence from Godard’s Le Mépris (1963) that is projected on to the wall of Miéville and Godard’s home, an intimate echo of Miéville’s own childhood projections. Their arms are visible and their doubled silhouettes that hover over the image of Raoul Coutard’s camera appear to be dancing or embracing, forming an open gesture that unites work and love.

JLG/JLG: Self-Portrait in December (1994)

Miéville and Godard may not give many interviews or talk readily about themselves or their films but their films never cease talking. Separately and together, we find in their work a plethora of unspoken signs that guide our attention to different corners of their shared audio-visual canvas. For example, in Godard’s film essay JLG/JLG: Self-Portrait in December (1994), a large film poster of Miéville’s first feature film hangs visibly on the wall in Godard’s editing studio. In front of the poster stands a blind editor, who Godard has hired to assist him with the montage of his film: a film one can listen to but that “no one has seen”. This whole episode constitutes a witty and tender tribute to Miéville, anticipating his later, more explicit homage to her in episode 4B, Les signes parmi nous, of Histoire(s) du cinéma, a project whose roots extend as far back as the mid-1970s when the Miéville-Godard partnership was in full swing.

The projection of the opening of Le Mépris at the end of Soft and Hard could also be thought of as an extension of Miéville’s The Book of Mary, in which the little girl, Marie, mirrors us, the spectator, as she watches a scene from Godard’s Le Mépris on television following the news that her parents are to separate. Soon after the commencement of Delerue’s sad theme music, Marie briskly and jarringly sings Beethoven’s Für Elise, which merges with the harmony of the film music.

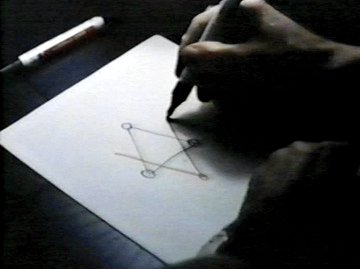

Her song swiftly changes into the tune from When Johnny Comes Marching Home, still underlaid by Delerue’s lingering music. Marie uses her singing voice to actively distort the haunting soundtrack as her father leaves the family home. This strange musical moment gathers meaning when understood through its connection with a later scene when Marie uses her hands to show her father the apex of a triangle. Like Miéville and Godard’s open arms in the final moments of Soft and Hard, Marie’s palms face outwards, this gesture presaging the uncontrollable force of her metamorphic dance.

~

► Watch Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin’s video essay Lines of resistance – Anne-Marie Miéville’s The Book of Mary. Anne-Marie Mièville’s collaborations with Jean-Luc Godard screen in the BFI Southbank’s Jean-Luc Godard season, running through March 2016.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.