Federico Fellini is one of a handful of directors whose style is so distinctive it has spawned an adjective. In much the same way as we say ‘Lynchian’, ‘Felliniesque’ tends to be used as shorthand for anything that is vaguely fantastical, dream-like, mysterious or even simply non-realist.

Fellini, a two-month celebration, runs at BFI Southbank through January and February 2020.

Our Fellini overview continues in our February 2020 issue, on sale now.

And while we should always remember that Fellini’s approach was originally forged in the ‘out in the streets’ era of post-war neorealism, when he worked with Roberto Rossellini on the screenplays for pictures including the canonical Rome, Open City (1945) and Paisà (1946), for most people, what comes to mind when imagining the ‘Felliniesque’ was a style that was created in, and reliant upon, the toy box that is the film studio – in particular Rome’s Cinecittà.

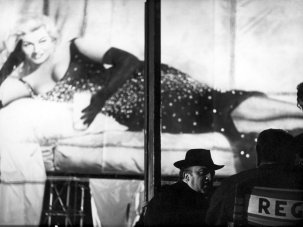

“Rome’s Cinecittà perks as Fellini’s Satyricon rolls,” ran the headline for a piece in Variety in October 1968. Pasquale Lancia, then head of the world-famous film studios, confirmed Fellini’s Roman epic would soon be taking over his soundstages for six months, “keeping most of the Cinecittà hands busy”.

When in Rome: Satyricon (1969) was one of many Fellini films to shoot at Cinecittà studios

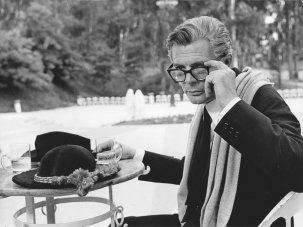

Few filmmakers knew how to keep Cinecittà busy like Fellini. Although his early films blended some location shooting with studio work, the director became increasingly attracted to the idea of building his filmic worlds from scratch and exerting complete control.

In a 1986 interview with Positif’s Jean Gili, he affirmed his belief that the studio is the only place where the filmmaker can recreate exactly what he or she has cooked up in their imagination. Like a painter with his canvas, Fellini told Gili, the filmmaker “is able to put together colours and tones, controlling distances, transparencies and perspectives”.

Fellini first stepped into Cinecittà as a young journalist in the late 1930s, shortly after the studios had opened. Like many of the major moments in his life, he reimagined it for the big screen, in 1987’s Intervista, a picture originally conceived to mark the studio’s 50th anniversary.

Fellini always envisioned his films as journeys, and it’s clear that inside or outside the studio, with or without protagonists at their centre, most of his works have a restless, wandering quality – something the director claimed was influenced by his collaborations with Rossellini. Fellini’s films are often bustling with movement, his characters moving in and out of teeming frames, some freely breaking the fourth wall – as in the famous final shot of Nights of Cabiria (1957), in Amarcord (1972) and elsewhere in his filmography.

Fellini’s characters often break the fourth wall, as in Amarcord (1972)

The whirling visuals are matched by equally free-floating and entirely post-synchronised soundscapes, which layer dialogue, sound effects and music. With sound as with image, Fellini was keen to oversee every last detail. If he felt an actor’s voice didn’t match their physiognomy, or if he wanted a voice to contrast sharply with the actor’s appearance (say, for comic effect), he would change it.

All of the performers who worked with him knew that the lines they delivered on set would more often than not be modified in post-production. Dubbing was the norm in most Italian pictures during the director’s long career, but with Fellini it assumed a poetic quality. As the French composer and film theorist Michel Chion notes: “We reach a point where voices… begin to acquire a sort of autonomy in a baroque and decentered profusion.”

Perhaps Fellini’s most succinct explanation for his decisive turn toward studio-based filming comes from the Gili interview, in which he was asked if it had amused him to construct a sea entirely of plastic for 1983’s And the Ship Sails On: “If you want to give the sea a feeling – the feeling of being a particular kind of sea – you can only do so with materials that can be lit a certain way, so they become […] dense with emotion.”

-

The 100 Greatest Films of All Time 2012

In our biggest ever film critics’ poll, the list of best movies ever made has a new top film, ending the 50-year reign of Citizen Kane.

Wednesday 1 August 2012

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.