The same hybridity is found in Vikas Bahl’s Queen (2014), a delightful feminist film in which a young woman, jilted by her fiancé on the eve of her wedding, honeymoons alone in Europe, and later thanks him for liberating her both from him and from herself. Starring Kangana Ranaut, it features a number of memorable songs and dances, with beautiful lyrics.

Another film in the season, Neeraj Ghaywan’s Masaan (Fly Away Solo, 2015), tackles the caste system and small-town India breaking the shackles of tradition, and has three stories that converge in Varanasi on the banks of the Ganges. It is elevated by Varun Grover’s philosophical lyrics, and deeply resonant songs by the band Indian Ocean. This debut feature won two prizes at the Cannes Film Festival.

There are few or no songs in three other films that play in the programme: Raman Raghav 2.0 (2016), Shahid (2012) and Court (2014). Based on the true case of a serial killer who lived in Mumbai in the 1960s, Anurag Kashyap’s Raman Raghav 2.0 is a violent thriller in which the lives of a cop and criminal mirror each other. Hansal Mehta’s Shahid dramatises the real-life tale of Muslim lawyer Shahid Azmi, who secured the release of many poor remanded prisoners, mainly Muslims imprisoned without evidence, and who was shot dead by right-wingers. Chaitanya Tamhane’s Court is a powerful debut feature focusing on the caste system and a Kafkaesque judiciary. It follows a shahir, a poet-activist-singer, who is arrested for inciting the suicide of a sewage cleaner through his song. Featuring mainly non-actors, it won two prizes at Venice, including best first feature.

Song and dance

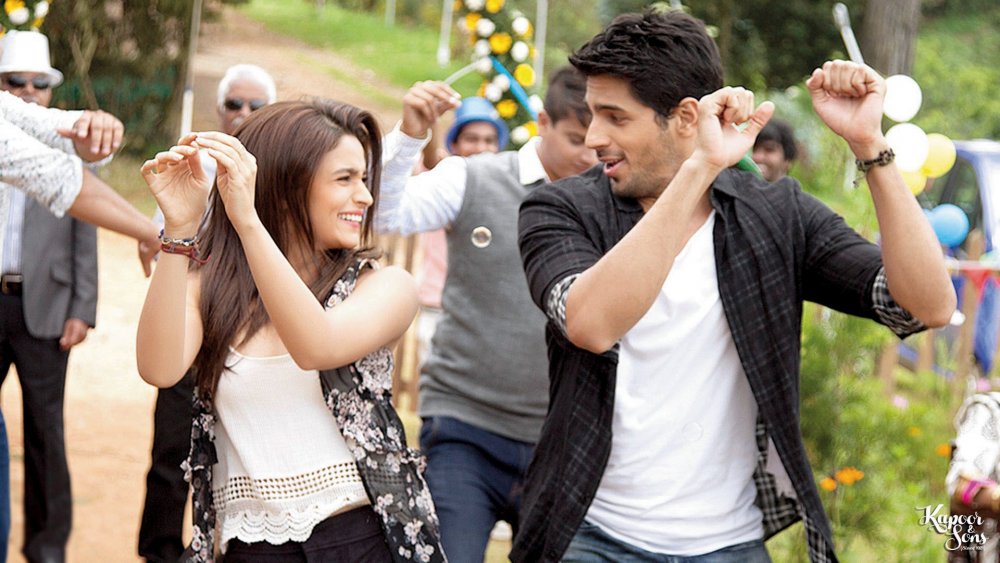

In May, the BFI’s India season turns to Song and Dance, a celebration of music in Indian cinema. Song and dance remains one of Indian cinema’s defining selling points, and song picturisation is India’s gift to world cinema – a sophisticated art that fuses poetry, music, choreography, cinematography, editing and, above all, rhythm. If you asked some of the world’s top directors to picturise a song, they would not be able to match the flair of Bollywood. The Chhaiyan Chhaiyan song and dance sequence at the beginning of Mani Ratnam’s Dil Se.., with its ensemble cast dancing on the roof of a speeding train, is one of the most glorious imaginable:

Much of the song and dance cinema of India has its roots in traditional folk. Included in the May programme is Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Bajirao Mastani (2015), an extravagant period piece with exquisite, sometimes jaw-dropping costumes, production design, music and dance. It portrays a historic Hindu-Muslim romance between the warrior Bajirao and the princess Mastani – politically courageous at a time of right-wing ascendancy. It is also daring for a contemporary Bollywood film to have its roots in Hindustani classical music, Islamic music and classical dance forms such as kathak. Along with Vishal Bhardwaj, Bhansali is one of Bollywood’s few gifted director-music composers.

Then there is Farah Khan’s Om Shanti Om (2007), starring Shah Rukh Khan, a wonderfully effervescent love story revolving around reincarnation. It features the popular singalong theme song Deewangi Deewangi. Farah Khan is one of the most successful female directors on the planet, with major box-office hits to her credit, and must be unique in being a choreographer turned successful mainstream director.

A.R. Rahman, who won two Oscars for Slumdog Millionaire, composed the music for Mani Ratnam’s Bombay (1995), a romantic, pacifist film set during Mumbai’s communal riots. Rahman also composed for Kandukondain Kandukondain (2000), an exhilarating Tamil version of Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, the title song of which was shot at Eilean Donan Castle in Scotland.

Film stars are divinity in India. No trip to Bombay is complete without a pilgrimage to gawk outside the houses of Bollywood stars Amitabh Bachchan, Shah Rukh Khan, Salman Khan and Aamir Khan. In Tamil Nadu state in South India, at least five film stars or scriptwriters have become chief ministers, including M. Karunanidhi, M.G. Ramachandran and Jayalalithaa Jayaram. But as top stars eat into profits, big Bollywood studios like Yash Raj Films like to churn out new stars, keeping budgets on a leash. A younger generation, such as Anushka Sharma, Kangana Ranaut, Alia Bhatt, Nawazuddin Siddiqui, Rajkummar Rao, Vicky Kaushal and Shweta Tripathi, are hungry to take risks with a diverse range of work.

Indian women with movie cameras

This appetite for risk has both deepened the indie film movement, and given India’s female directors a new space in which to thrive. Many of them are showcased in a season of films at the BFI Southbank in July. One such is Nandita Das, whose film Firaaq (2008) is extraordinarily courageous for being one of only two features made about the Gujarat riots of 2002, in which, according to official figures, 790 Muslims and 254 Hindus were massacred and more than 50,000 Muslims displaced. Das sets her haunting film in the aftermath of the riots, obliquely addressing them through sublimated emotions.

Also screening is Konkona Sen Sharma’s A Death in the Gunj (Hindi/English, 2016), an impressive debut from an accomplished actor, who is also the daughter of filmmaker Aparna Sen. A Death in the Gunj is set in the 1970s during a family reunion in the colonial town of McCluskiegunj, in which a young man’s feminine characteristics provoke both men and women. Sumitra Bhave and Sunil Sukthankar’s Astu (So Be It, Marathi, 2013), while ostensibly about a grandfather who has Alzheimer’s, makes an astounding philosophical connection between loss of memory leading to loss of identity, and one’s persona dissolving in the Absolute – the aim of Hindu philosophy.

The Indian indie movement has been consistently producing world-class films for some years now. Despite festival acclaim and precarious domestic distribution, an increasingly appreciative audience at home is helping modestly budgeted productions to recover or even make some money. Ritesh Batra’s The Lunchbox (2013) sold in an astonishing 70 nations worldwide – far beyond the traditional Bollywood diaspora territories.

The profile of the Indian audience is rapidly changing. There is an increasingly sophisticated audience exposed to world cinema and to online web series made by the likes of Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, Hotstar and Eros Now in India. Middle-class consumers are increasingly watching moving-image content on their smartphones – India now has well over 220 million smartphone users, surpassing even the US. There has been an explosion in the number of young people enrolling in mass-media colleges nationwide, feeding the entertainment industry, and there are dozens of international film festivals taking place across the country, including those in smaller towns such as Gorakhpur, Bareilly and Madurai. All this has whetted audiences’ appetites for diverse films in regional Indian and world languages, and for different kinds of storytelling.

As for Hollywood, despite dubbed releases in English, Hindi, Tamil and Telugu, its future in India looks less than rosy. While big US releases retain some loyal audiences in India, many of the big Hollywood studios, including the Walt Disney Company, Sony Pictures India and Warner Bros, are either shutting down their Indian motion picture arms or have already shut up shop. Fox Star Studios India is coasting along mainly through a partnership with Bollywood’s Dharma Productions.

A glance at bookmyshow.com, a popular Indian online ticket booking website, show that Bollywood and Hollywood films are in a minority: there are far more screenings of regional-language films in Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Marathi and Bhojpuri. It suggests that the future is ‘glocal’: you can be universal by being local.

-

Sight & Sound: the April 2017 issue

Kristen Stewart, the star for our times, plus Paul Verhoeven and Elle, The Love Witch, Graduation, Jacques Becker and the range of Indian cinema.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.