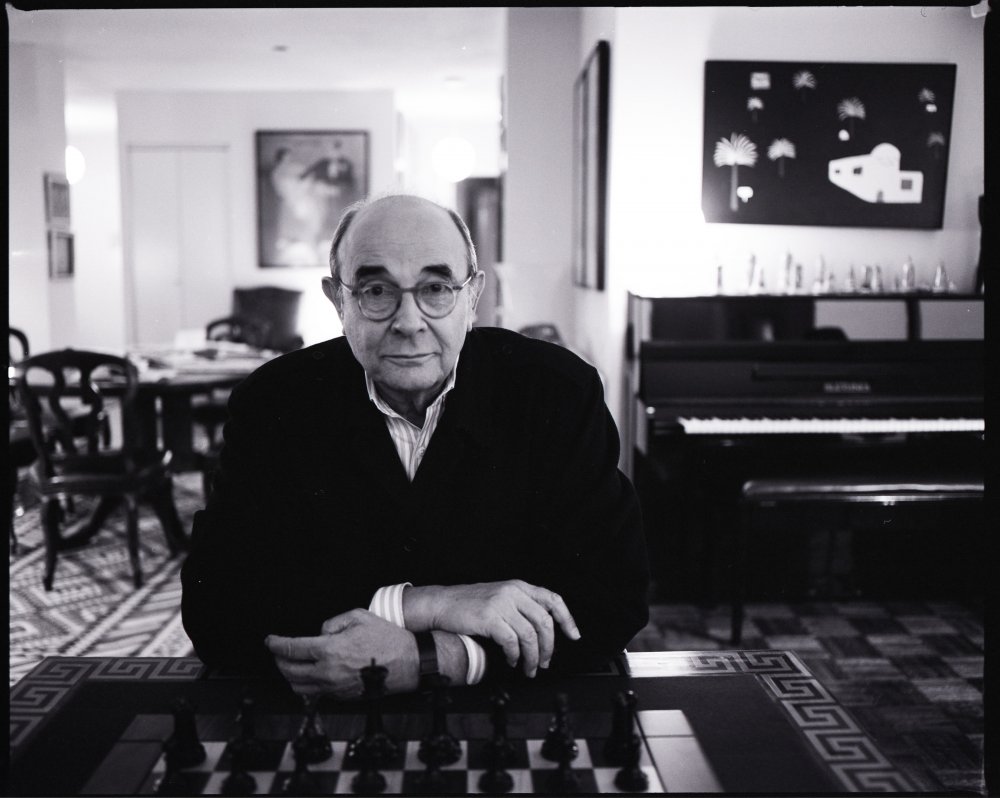

Dear Stanley Donen,

Finally, you’ve gone. To be honest, it was remarkable that you were still here, in 2019, because you were so connected to a golden age in Hollywood, and, through Singin’ in the Rain’s rear view mirror look at silent cinema, even further back. You once said that, when you got into film in the early 1940s, it felt that silent cinema had not long ended.

Should we stop all the clocks as a result of your death, put crepe bows round the white necks of the public doves and let the traffic policemen wear black cotton gloves? No, though your movies rank as highly as William Wyler’s or Michael Curtiz’s, you were too much fun for such mourning, and too hard-hearted.

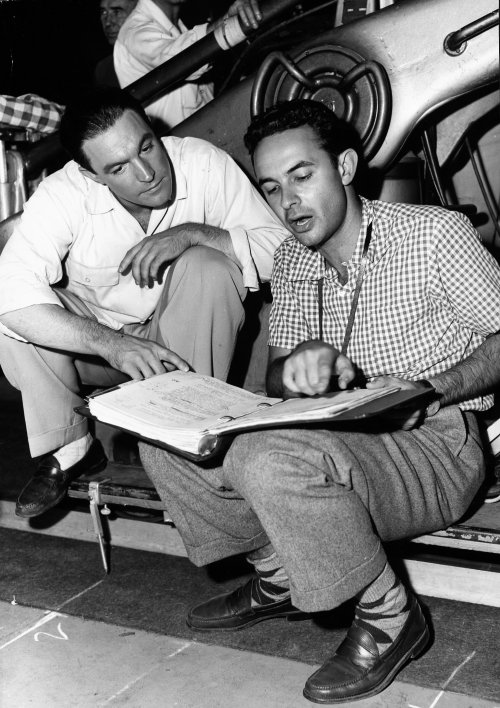

Stanley Donen (right) with Gene Kelly on the set of Singin' in the Rain (1952)

When you died I thought of a not well known number – The Leg of Mutton Dance – in Deep in My Heart (1954). You won’t remember, but you and I argued about this movie. I said it was one of your best. You said that you only did it because of producer Roger Edens. It’s about Viennese composer Sigmund Romberg, of course, and the clash between his sophisticated European music and the hotsy-totsy entertainments of Broadway. The dance is silly, feels improvised, and is one of the most entertaining things I’ve seen on film. It captures a momentary joy. Its characters are not thinking, they’re having fun. It’s called mindfulness, these days.

Is that the central theme in your work – the fun of Eden, the joy before the fall? Can we talk through your films to see if that’s true?

Your childhood in South Carolina wasn’t Eden. You were bullied and bored, and Hollywood was a continent away, but you got there and did On the Town (1949). It was already about the moment – a day in the life of sailors and their girls. It was European in a way, like a René Clair or Ernst Lubitsch movie, and what was noticeable was how libidinous the women were. Betty Garrett, particularly in the Come Up to My Place number, was sexually voracious, a pre-echo of Ingrid Bergman’s “I need a man, tonight, here, right now” in Indiscreet (1958). You said later that On the Town is about “how much juice there is in life”.

Frank Sinatra, Gene Kelly, Jules Munshin and Betty Garrett in On the Town (1949)

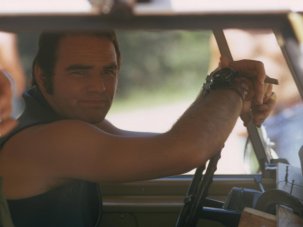

There was a lot of juice in Singin’ in the Rain (1951). It brought new tones to your emerging voice as a filmmaker. At its centre was a threesome – Gene Kelly, Donald O’Connor and Debbie Reynolds – and this repeated throughout your movies, especially Lucky Lady (1975). In the latter, the Gene Hackman, Liza Minnelli and Burt Reynolds triangle become more sexually explicit, and didn’t you plan an ending in which the three would be seen as old people, in bed together? Friendship was a key element in your Eden.

But there was more to Singin’ in the Rain, of course. It had the same clash between high art and popular entertainment – between the intellect and the body – as Deep in My Heart. Reynolds thinks that the stage is superior to mere movies. Did the fact that you didn’t go to college help you choose films about this subject? Funny Face (1956) is more explicitly about that theme, and errs (I feel) on the side of anti-intellectualism.

Fred Astaire and Audrey Hepburn in Funny Face (1956)

Then of course there were the split screens in Singin’ in the Rain. “Yes, I used split screens a lot”, you said to Bertrand Tavernier and Daniel Palas in 1973, and there they are in Funny Face, Royal Wedding (1950), Damn Yankees (1958) and that famous split phone call between Cary Grant and Bergman in Indiscreet. If you are into threesomes or more, then it makes sense to split the screen, but they are, also, about the moment. A flashback shows the same people at different times, but a split screen shows different people at the same time.

And as I mentioned flashbacks, can we touch on the time structures in your films? You and your great screenwriters – Betty Comden and Adolph Green on Singin’ in the Rain, Frederic Raphael on Two for the Road (1967), Peter Cook and Dudley Moore for Bedazzled (1967) – seemed to like complex story backbones. Singin’ in the Rain has that big flashback in the first half, then the ‘flash to’ pas de deux in the second half. Two for the Road’s present tense hardly advances at all, so chambered it is with time shifts. And Bedazzled jumps seven times from its present tense to Dudley Moore’s wishes, which are all bound to fail.

This raises the question of what happened when your own timeline advanced, when you got older. It’s Always Fair Weather (1955) was an unofficial sequel to On the Town, wasn’t it? It’s ten years later. TV is atomising American life. You said that it was “subtle and scathing at the same time”, that “everything is derision in the film… even its title is satiric.”

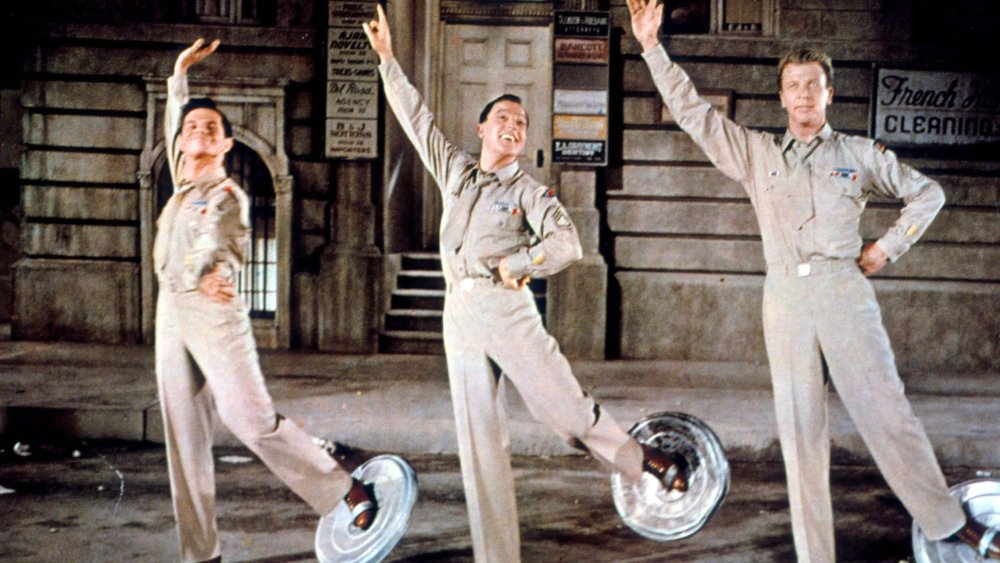

Michael Kidd, Gene Kelly and Dan Dailey in It’s Always Fair Weather (1955)

What had happened? You were only 30 when you made it, but had done nine films, were already divorced from Jeanne Coyne, would divorce Marion Marshall a few years later and were undergoing the painful split from Gene Kelly. You were losing your optimism, and squeezing out the juice of life. The H Bomb was being built and the Korean War had started. You had more to remember and more to fear. It was harder to sing in the rain or do the Leg of Mutton Dance.

And so you played it safe for a while, adapting musicals and plays into films. The Pajama Game (1957) again had strong female perspectives, and was the best thing Doris Day ever did. You must be proud of the There Once Was a Woman and Hernando’s Hideaway numbers, aren’t you? And Once a Year Day, which you choreographed with Bob Fosse, was one of your last Edenic moments. Those camera moves! How did you learn to plan them so well? I’m thinking also of the ones in the Thames nighttime walk following Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman in Indiscreet, made the next year. Every time I walk the Thames Embankment I think of them, their grace, their elegy.

Ingrid Bergman and Cary Grant in Indiscreet (1958)

For a filmmaker interested in Eden, it’s no surprise that there are devils in your work. In Damn Yankees, also 1958 (were you not exhausted? This was your 14th film and you were only 34!) Ray Walston is a kind of Faust, and Peter Cook is another one in Bedazzled. Of course your screenwriters scripted these stories, but you chose them and, of Bedazzled, you said “It’s a very personal film in that I said a great deal about what I think is important in life… [it’s] the one of mine that has more to say.” Dudley Moore’s character finds it impossible to stay in the moment, to sing in the rain, and Peter Cook’s line “Adam and Eve were happy because they were pig ignorant” seems to pull the carpet out from under the hotsy-totsy naivetes of The Leg of Mutton Dance.

Lucky Lady, which came in 1975, seems to have been equally personal. Minnelli-Hackman-(Burt) Reynolds are escaping the kind of drudgery that you felt in your childhood in South Carolina. They are the offspring of Kelly-O’Connor-(Debbie) Reynolds, but with a new tone. The wheel has spun, their highs are more pastiched, and their lows? Maybe they don’t even realise that they’re unhappy, that Eden is far away.

Liza Minnelli, Rurt Reynolds and Gene Hackman in Lucky Lady (1975)

And the imagery in your films show that. Your MGM movies are so polished, so visually sure, so controlled. Their moments are perfected, but the shots in Staircase (1969), starring Richard Burton and Rex Harrison, and Two for the Road, both filmed by Chris Challis? There’s a new roughness and plainness. We get zooms, handheld shots, and what seem like unplanned moments. The images have absorbed the new social uncertainties about sexuality and the future. People no longer live happily ever after, and so the moment is more fleeting than ever. The key line in Two for the Road, I think, is “The world is changing beyond recognition. There is no such thing as permanence any more. And we should be glad.”

Rex Harrison and Richard Burton in Staircase (1969)

Let’s not stop the clocks, Stanley. They aren’t stoppable, as Two for the Road shows. We’re all aging, and we’re further away than ever from the MGM Eden. That’s fine.

When we did the retrospective of your movies at the 1995 Edinburgh International Film Festival, we learnt the Leg of Mutton Dance. I can still do some of it. We remember the dances of our youth.

Let’s do it again, now, but wearing black cotton gloves.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.