Web exclusive

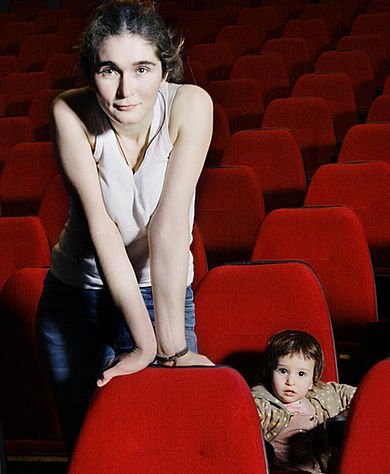

Maria Saakyan in 2007

Credit: Nora Jane (norajaneart.com)

At the end of January, the film world was alerted to the tragically early death of writer, director and producer Maria Saakyan by a Facebook post from Russian film critic Andrey Plakhov. He noted that Saakyan had died of cancer, and wrote: “It is impossible to believe in the death of a beautiful 37-year-old woman. The bright memory… condolences to the relatives.”

So Mayer and Second Run DVD’s Mehelli Modi will present a special screening of Saakyan’s debut The Lighthouse at the London Review Bookshop on 5 March 2018l.

Saakyan came to international prominence with her first feature The Lighthouse (Mayak, 2007), made when she was 27, about a young woman, Lena, returning from Moscow to her home village in the Caucasus as war continues. It was supported by the Hubert Bals Fund of the International Film Festival Rotterdam, where it was first shown, followed by screenings at the BFI London Film Festival and more than 40 others. A number of critics selected it as their film of the year for Sight & Sound in 2007, with SF Said describing the film as “An incendiary mix of war film, memoir and musical explosion, it was hands-down the debut of the year, standout of the London Film Festival, and richly deserves theatrical distribution in 2008.”

The Lighthouse (Mayak, 2007)

The Lighthouse did receive a theatrical release in Russia, where Saakyan’s family had relocated in 1992 from Yerevan, Armenia, due to war in the South Caucasus. Saakyan attended the prestigious Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) in Moscow, studying with Vladimir Kobrin. She graduated in 2003, and worked as a creative producer for three years with Andreevsky Flag. Her graduation short film Proschanenie (Farewell) is a an elliptical but deeply personal film (dedicated to Saakyan’s father), meriting comparisons to Andrei Tarkovsky, about a girl coming to terms with the death of her father, an artist who had suffered from depression. It premiered at Rotterdam and Telluride.

The Lighthouse received English-language DVD distribution from Second Run, and its international success led Saakyan to co-found a production company in Yerevan with one of the film’s producers, and to put together her second feature, I’m Going to Change My Name (Alaverdy), as an independent international co-production with support from the World Cinema Fund, Danish Film Institute and Goteborg Film Fund. She was a FrameWork participant at Torino Film Lab in 2009 and a Berlinale Talent Campus participant in 2010, and the film won Best Pitch at B2B, Belgrade. An ambiguous mother-daughter story with deep mythic roots, I’m Going to Change My Name sets ancient Armenian choral music against a modern world of suicide websites and stunning digital animation.

I’m Going to Change My Name (Alaverdy, 2012)

In 2013, Saakyan’s third feature, Entropy (Entropiya), an experimental comedy about the end of the world, was released in Russia. Winning the Savva Kulish Prize at Vyborg in 2012, it was her most locally focused film and, tonally, a world away from her previous work, a scathing satire on Russian media and independent auteur cinema. Punk filmmaker Valeria Gai Germanika (known as ‘Russia’s Larry Clark’) stars as an outré director, with Russian TV anchor and socialite Ksenia Sobchack as her power-hungry producer. The only professional actor in the film was Evgenii Tsyganov, who had played Petr, the absentish father, in Alaverdy. In 2014, Saakyan stepped away from feature filmmaking, giving workshops at TUMO, Armenia and directing the opera Ring of Fire by Avet Terteryan. Via Anniko, she also produced a comedy by Arsen Aghadzanyan, Honey-Money, which premiered at Viborg in August 2015.

In 2014, Saakyan noted on Goodreads that she was reading Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, and her first two feature films share with Woolf’s novels an absolute commitment to representing inner life, finding a cinematic language for the mixture of observation, experience, dream, fantasy and hallucination that fleets through our minds. Both The Lighthouse and I’m Going to Change My Name focus on young women who, like Clarissa Dalloway, go for a walk in an outside world marked by war and its aftermath. Their daily tasks are marred by violence, either present or remembered, and it is through the imaginative ways in which they respond to trauma that the everyday is lifted into the poetic and epic. The Lighthouse opens with a quotation from a poem, and I’m Going to Change My Name reworks the Armenian epic poem Sharakan, a version of the Orpheus and Eurydice story. Grounded in quotidian embodiment, as in the long sequence of Evridika rising up on the cable car in I’m Going to Change My Name or the hair-washing scene in The Lighthouse, Saakyan’s ambitious films were – because of this physicality – never less than visionary.

Entropy (Entropiya, 2013)

And not just her films, but her filmmaking: with Victoria Lupik, Saakyan co-founded Anniko Films in 2009 to produce films in Armenia – or really, to produce a non-diasporic Armenian cinema. Anniko produced all of Saakyan’s films, in a country and region with no established post-Soviet national film industry. Nick James gives a brief history of Armenian cinema in his account of sitting on the Golden Apricot (Yerevan International Film Festival) jury, which awarded Saakyan her third Best Film prize at the festival. The relationship between the filmmaker and festival clearly went deep, with the festival posting on its website after her death: “We love Masha not only for her talented films but also for the fact that when she was entering our semi-dark office she was always bringing light with her frisky and cheerful essence.”

Maria Saakyan at the Amiens International Film Festival in 2008

As Entropy brought out, Saakyan’s ‘semi-dark’ films always had a strong absurdist streak; while she was committed to experimental film language, she was always contesting the borders of cinema. In Political Animals, I used Alisa Lebow’s category of the ‘unwar’ film to describe The Lighthouse; likewise, I’m Going to Change My Name could be called an ‘uncoming of age’ film. Saakyan’s films bridged the contradictions of her life: she was a deeply local filmmaker without being a nationalist one, and – unlike her father, who left his family – committed to her art while also focused on being a mother of five.

In just over a decade, she revolutionised the Armenian film industry and the international standing of Armenian cinema and invented a uniquely poetic language for female interiority. In a particularly poignant scene in The Lighthouse, an elderly woman called Kasyana tells Lena of her dream of being a pear tree. She says: “In me, the tree, the world is moving.” Saakyan’s films brought this earthy, ordinary mystery to the screen; in them, her films, she continues moving.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.