Before you can say anything useful about Armenian cinema, you have to know about Armenian history and politics. That is certainly the assumption made by the Yerevan Film Festival, where I recently served on the jury for their Armenian Panorama section. Among a very mixed bag of shorts, fiction features and documentaries drawn from across the diaspora, many works were anxious to explain different facets of the national dilemma. And given that the feelings towards identity of those who originate from this country are often complex, one can understand the anxiety to educate.

|

Golden Apricot Yerevan International Film Festival 7-14 July 2013 | Armenia |

So, first, a potted geopolitical lesson (with apologies for any unintentional glibness): Armenia is a landlocked former Soviet republic, which borders on Turkey to the west, Iran to the south, Azerbaijan to the east and Georgia to the north. There was an ancient kingdom of Armenia, but for centuries the region was much-disputed between the Ottoman and Persian empires.

From the sixteenth century to the nineteenth, the majority of Armenians were Christian citizens of the Ottoman Empire and therefore vulnerable to discrimination. Attempts to reform their status continued throughout the 19th century but culminated in 1894-96 in punitive massacres of Armenians.

After the First Balkan war of 1912, The Ottoman Empire began to disintegrate. Many of the Muslims expelled from the Balkans were settled in areas traditionally inhabited by Armenians.

When the new Turkish state allied itself to the Central Powers in World War I, the military authorities mistrusted the loyalty of Armenian troops and had them disarmed. The 1915 genocide (a word coined for this appalling event) arguably began with a dispute between the military and the armed Armenians of the city of Van, close to the front line with Russia. This soon led to the wholesale deportation from Turkey of people from nations thought to be potentially sympathetic to the Russians, mainly Greeks and Armenians.

In the case of Armenians, however, there were acts of deliberate mass slaughter, resulting, evidence suggests, in the deaths of somewhere between 600,000 and 1.5 million Armenians, maybe more. Those who survived washed up all over the globe but particularly in the Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, France, the USA and Canada.

Tamara Stepanyan’s Embers

What becomes obvious if you watch the range of films I’ve seen is that the generations of displaced Armenians carried with them an iconic idea of their homeland that today’s reality can hardly sustain. Western Armenia is still a part of Turkey and Armenians remain part of the Turkish population. There are also some Armenians living in Georgia, and to the east in Nogorno Karabak, a region over which Armenia fought a war with Azerbaijan, and which is currently under Armenian military control.

It seems, however, that the Armenian state itself cannot sustain the agrarian part of its economy. Figure of Armen, a beautifully shot, straightforward interview-based documentary by Canadian-born Marlene Edoyan, concentrates on the rural populations at the edges of Armenia, and is crucially informative about all of this. It is noticeable that the elderly peasants she talks to, whose children mostly have to find work abroad or in the city, often regret the passing of the Soviets.

So too do many of the nonagenerians whose testimony comprises Embers, by the Lebanon-raised, Paris-based Tamara Stepanyan. Her late grandmother had been the “life and soul” of a group of former soldiers who had fought the Nazis under the Soviet banner and who gathered once a year with their wives and husbands to celebrate their victory. The filmmaker visits the few remaining survivors in Armenia and painstakingly builds a sense of how it was from patient interviews and images of memorabilia. This simple film makes an effective point about the generation it describes, even if it stretches itself somewhat too indulgently.

Lusia Dink’s Saroyanland

An entirely different sort of diasporan return inspired Turkish-born Lusia Dink’s Saroyanland, which poetically recreates the 1964 road trip made by distinguished US-Armenian author William Saroyan to Bitlis, the town his parents left after the 1890s massacres. It’s made up of telling quotes from Saroyan’s pithy, straight-from-the-shoulder books and eloquent shots of a 50s-model Ford driving though Anatolia that contains a bewhiskered man in a hat and coat who we never quite see – except in actual stills from the time, or as a shadow cast on the rocks. I found the voice reading Saroyan rather abrasive and aggressive, but I never heard Saroyan himself read, so perhaps that’s what he sounded like. In any case, Saroyanland was well deserving of the Golden Apricot for Best Documentary that our jury gave it.

Recreations of the genocide itself were glimpsed in Ara Yernijaknan’s well-made, if overwrought, one-idea short Eclipse, about children in an American Red Cross rescue camp, and in Arto Pehlivanian’s French-financed feature-length documentary V for Verneuil, a portrait of the prolific French-Armenian director Henri Verneuil. Born in Turkey as Ashod Malakian, Verneuil fled when a child with his Armenian parents to Egypt and then France, where he became successful film director making comedies with Fernandel and later action movies with the likes of Jean-Paul Belmondo and Omar Sharif.

More to the point, at the end of his career, he made two feature films based on his recollections of his parents’ terrible journey into exile: Mayrig (Mother, 1991) and 588 Rue Paradis (1992). Clearly a larger-than-life figure, Verneuil comes across as a beloved, sincere arch-sentimentalist, and the scenes from his autobiographical pair of films make Dr. Zhivago seem restrained in its lyricism. No wonder Verneuil chose Sharif to play his father.

Verneuil’s Mayrig (Mother, 1991)

The more recent 1988-94 conflict in Nagorno Karabach between Armenia and Azerbaijan (which resulted in claims of atrocity from both sides) provided the setting for another war-torn dramatic reconstruction of terror. Jivan Avetisyan’s Broken Childhood concerns the fate of a six-year-old Armenian girl who survives the Maragha massacre and is handed to an Azeri mother who looks after her tenderly in hopes of exchanging her for her son, who is missing at the front line. There isn’t much more to the narrative than that and – again – this shortish film (46 minutes long) opts for an overly theatrical style of performance (at least to Northern European eyes). Yet it sustains a palpable tension that keeps you watching.

Though this kind of material dominated what I saw, my stay in Yerevan was not all steeped in regional identity politics. Yerevan is a city hoping like any other to thrive in the globalised future. It has its new shopping malls and bristles with restaurants, many of which laid on for the festival guests huge wedding-like celebrations at which there was lots of traditional dancing (of which I hope no footage in my case exists).

Jivan Avetisyan’s Broken Childhood

There were also Soviet-style honorific ceremonies – Atom Egoyan and Arsinée Kahnjian happened to be sitting next to me when they each got an honour; Khanjian’s was a medal on a red ribbon, Egoyan’s a huge star-like object that made him look implausibly like a Lord Mayor. One standout Yerevan building was the Tumo Centre for Creative Technologies, a brilliant facility for young people keen to exploit access to powerful IT, where Egoyan ran an absorbing panel discussion on transmedia that tried its best to rescue the form’s potentialities from those who would confuse marketing with content.

There were some films, too, that didn’t pertain at all to Armenian fates. Godfrey Reggio, of Koyaanisqatsi fame, showed us half an hour of his new work Visitors, a 4K black-and-white digital presentation that will premiere in its complete feature-length form at the Toronto International Film Festival in September. The images in the sequence we saw mostly show people watching television or video games in exaggerated slo-mo, unconscious of being filmed themselves. As usual, Reggio’s images are set to the music of Philip Glass and the sample I saw was visually remarkable and captivating, even if it didn’t quite live up to Reggio’s rhetoric of his films being designed to deprogramme our corrupted vision of the world.

Of the Armenian films I haven’t mentioned, I’ll leave aside the local rock opera, Wandering, a weak rejigging of an idea similar to A Matter of Life and Death that could only be endured.

But I can’t resist remarking upon the portentous claptrap that was The Voice of Silence, by actor-director Vigen Chaldranian, one of the most egregious vanity projects ‘based on a true story’ I have ever seen. Chaldranian plays a Hollywood-Armenian actor-director who finds the muse for his next film living rough in a rubbish dump. Designed, it seems, to show us what a deeply sensitive character Chaldranian is, The Voice of Silence is in thrall to its belief in its own achievement. Shakespeare, Fellini – they’re all in there, if only to illustrate that Chaldranian is on their wavelength.

Probably the greatest of Yerevan’s attractions is the Sergei Paradjanov Museum. I could have spent a whole day being wowed by the sheer invention of the director’s myriad collage works and by the superb atmosphere of the building itself, not to mention the images from his films such as Shadows of My Forgotten Ancestors.

As we later learned from Serge Avidekian’s biographical movie Paradjanov, the director apparently described himself as Georgian-born, of Armenian parentage and accused of promoting Ukrainian nationalism – a deft way of sidestepping others’ attempts to claim or pigeonhole him. Biographical fiction on screen is not usually my cup of tea, but Paradjanov (the movie) eschews the conventional birth-genius-death narrative in favour of a more elliptical approach to the life. It’s closer in approach to Ken Russell’s highly imaginative big-screen composer biographies such as The Music Lovers and Mahler.

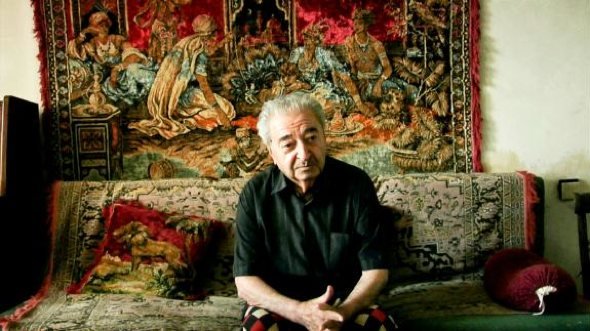

Artzavazd Peleshian (left) at the Yerevan International Film Festival

Armenia’s other great film genius is Artavazd Peleshian, whose eloquent poetic shorts made between 1964 and 1994 are famous for their gentle visual strength and lack of spoken dialogue. World of People (1966), Inhabitants (1970), Seasons (1970), The End (1994) and The Life (1993) were shown here as a tribute retrospective, representing around half of his life’s work.

By coincidence I happened to be sitting next to Peleshian – whose grave looks resemble an Easter Island statue – at the closing-night ceremony, and watched him bear the constant scrutiny of his country’s paparazzi. When his name was announced he got a huge round of applause and stood up with his hands clasped over his head to receive it. It’s a pity his work is so hard to see on DVD. It is suggested by some that Peleshian owns his own prints and perhaps has an exaggerated idea of their value to DVD distributors.

But I’ve written nothing here about the biggest star at the festival, who is also the world’s most famous Armenian – Charles Aznavour. He received the near-adoration of his originating country here with a certain dumbfounded amazement. When Egoyan bade Aznavour come to the stage of the Opera House to receive some kind of lifetime achievement award, he did not appear (perhaps it was all too much), and Egoyan had to leap upstairs to find the balcony where he was. It was a pity that the screening of Shoot the Pianist that followed was so poorly projected as to be unwatchable.

I’m Going to Change My Name (Alaverdy, 2012)

But to finish, the film to which our jury gave the Golden Apricot for Best Film was I Am Going to Change My Name by Maria Saakyan, which played last year in the Experimenta section of the BFI London Film Festival. It’s a fanciful, impressionistic, delicate portrait of a 14-year-old girl, Evridika (Aina Adju), whose mother Sona (Maria Atlas), a choir conductor, is more often than not away on tour – leaving Evridika to her adolescent perceptions of Alaverdi, the industrial town where they live, its romance and its dangers.

The reappearance of Sona’s ex-lover, Pyotr (Evgeny Tsyganov), initially propels Evridika further away from her mother and into a potential danger from which Pyotr happens to rescue her. Later, when Sona sends Evridika away to her aunt in Yerevan, she runs into Pyotr again – now split from Sona a second time – and a deeply Freudian encounter between the two leads to a watershed in Evridika’s life.

It’s a beautifully made film and felt like it had all the identity trauma it needed without one reference to Armenia’s troubled history. Armenia needs more films that look inside out rather than outside in.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.