Web exclusive

Antonia Bird at Studio 7070 in Los Angeles in 1995

One afternoon in early 1993, I was sitting in my flat in Edinburgh, selecting films for the British section of the Edinburgh International Film Festival. I put into my VCR a video of a BBC film called Safe. By the end of it I knew that it was, by some distance, the best British film I had seen that year. I compared it to Vittorio de Sica’s film The Bicycle Thieves.

When Safe’s director, Antonia Bird, came to the festival, I started to realise how distinctive and significant she was. Many directors in those days were interested in gloss, heritage, the kind of cinema that tidied life up. The director that I met talked of social class, of leftist politics, of passion and possibilities. When she spoke, her eyes lit up, welled up, fired up.

We screened the film for the press. The Times, I seem to recall, wrote “Ken Loach and Mike Leigh, do not rest on your laurels… this film brought me to my knees.” Tickets for Safe were not selling all that well, so we made flyers with the Times quotation on them, and Antonia and I handed them out on the street. In the 90s, it was street, not tweet.

As a result of our leafleting and the other reviews of the film, we got a full house. Antonia was nervous about showing the film, but bounced on stage to introduce it and spoke with passion, and went red, and kept pulling her hair back from her face, and, in what she said, connected cinema to principle.

Then the lights went down, and the film ran. And then the lights went up and people stood up: an ovation for this energy ball and her tableau vivant of real people and deep truths.

In those first encounters, I became hooked on Antonia Bird, and still am. We showed her next film, Priest, which was harder to get for the festival because Antonia’s work was now in demand. It added real sexiness to her palette – in retrospect her films so far have been born of an erotic imagination as well as social and cinematic ones. Her film Mad Love got mangled in America, yet even it demonstrated that this filmmaker was on the march towards a cinema of passion, of heat and ire, of engagement and engorgement.

With Face, Antonia showed that she had mastered male milieu and, also, musicalised it in some sense. The social and gender truths we saw in her movies seemed choreographed and were scored by composers like Damon Albarn and Michael Nyman. The urgency of Antonia’s imagination was underscored by drumbeats, as if history was on the march or banging bin lids in protest.

On the Warsaw Film Festival jury in 2010

By this stage, Antonia’s cinema was richly layered – society, gender, eros, masculinity, musicality – but as I watched from the sidelines, I couldn’t foresee what would happen next. Ravenous. A film about cannibalism, which unearthed something that was thus far buried in her work: the fact that in the capitalist rat-race, we sort of consume each other. Typical of Antonia and her writing collaborators, however, was the fact that this central metaphor was not revealed in literary terms. Instead, Antonia reached for that most full-blooded of genres, the horror movie, to show what she’d been on about all along. Ravenous was a masterpiece – not Antonia’s first great movie, but her fullest.

At this stage my life crossed with Antonia’s again. She spied that it would be best to have her own production company, so asked Irvine Welsh, myself and then Robert Carlyle to join her in what we called 4Way Pictures. I had kept making documentaries through the 90s, but jumped at the chance to see inside Antonia’s working methods. I was supposed to be the producer in the team, which didn’t work out because I was more director material, but I worked closely on the development of The Meat Trade, written by Irvine and Dean Cavanagh and to be directed by Antonia.

In many hours of script sessions, over several years, I noticed how Antonia saw inside the film’s complex story. Irvine and Dean had written a narrative structure of engineered precision. Move one bit of story and lots of other things needed to be re-tuned. To see this structure, I had to write it on bit sheets of paper, but Antonia seemed to be able to hold its matrix, its many characters and scenes, in her head. And, when we talked about what she called character beats, I saw how she could sweep down from an overview of the film into a moment or exchange or line of dialogue, and describe how it might be played, how dramatic it should be, whether it was part of a build-up of feeling or an ebbing away.

We pitched the film in Cannes, sitting all day on a balcony, doing meeting after meeting. Antonia was the liveliest of us all in such pitches, getting worked up and sweaty as she’d describe the story, its scenes and emotions, with gusto.

We drove around Edinburgh on a recce to find locations. Blocks of flats near Stevenson College, which are no longer there, caught her imagination, as did housing near Craigmillar. As I accompanied Antonia, I felt that I was seeing through her eyes. As I noticed what she noticed, I began to realise that she was picking up on extremely widescreen compositions, social cineramas, almost. She never looked through a viewfinder but her choices were clearly those of the person who made Ravenous, whose eye had become attuned to a certain epic mode, something like Sergio Leone.

Antonia’s cinematic imagination had developed since the intimacies of Safe. Wedded to Welsh’s great, grand guignol tale, which had elements of Edgar Allan Poe, Antonia was picturing for The Meat Trade something luscious and vicious, like Tarantino, a grand-scale movie indictment of the commoditisation of our times.

Antonia took me to meet her friend Rebecca, through whose experiences she began to plan a film about HIV. Maybe a documentary? Maybe shot with little cameras?

As the cinematic ground was shifting under our feet, as digital was miniaturising the filmic process, the epic mode was starting to be harder to fund, so it was right to think in that direction. Maybe the scale of The Meat Trade was too big to realise – at least so far – and, almost certainly, those who funded films found her excoriating vision for this film and others – what? – excoriating?

But Antonia stepped sidewise to make award winning slices of life (Care and Rehab) for TV. Again, she, her writers and actors, went digging for truth.

And then came The Hamburg Cell, an intense, acclaimed and very relevant response to 9/11 which, typically, saw the planning of the attack not from some lofty distance, but from inside it.

There were other promising film ideas – The Widow, written by Naomi Wallace and Bruce McLeod, and an extraordinary film, 90 Days, an account of the brutality of life in San Diego when you are near the bottom of the heap, to name but two of many. Antonia had spent enough time in America to know that some of its social hope was quixotic. She and I even hoped to co-direct a musical, Scotston, starring Kerry Fox.

All filmmakers have had many unrealised projects; I’m mentioning these because I witnessed, over several years, the energy with which Antonia kept so many of them spinning. We talked often about such spinning, its frustrations, the fact that it was born out of Antonia’s reluctance to compromise the intensity of her attack, her refusal to put down the social X-ray specs. I’m not sure how often we have said so far that Antonia had to spin so many plates in part because she is a woman, and that the funders fund films by men more than women. The latter is a fact, of course.

Antonia has made great cinema and, through great will, has shown lives on screen which without her might never have got there. She knows that the movie and TV screens are places that reveal truths; the layers of her visual, social and character imagination have heated those screens to a temperature that few UK directors have essayed.

There’s the ebullience of Hong Kong cinema about her best work, an Old Testament moral force, a grand gesture. I wish Antonia had directed Lawrence of Arabia (she would have made it much better than it is), and the recent French film Untouchable (ditto). She’s as significant to British cinema as, say, Alan Clarke.

And she’s a wonderful friend.

Gallery: Antonia Bird’s feature films

-

Robert Carlyle in Safe (1993)

-

Carlyle again (right) with Linus Roache in Priest (1995)

-

Chris O’Donnell and Drew Barrymore in Mad Love (1995)

-

Ray Winstone in Face (1997)

-

Robert Carlyle and Guy Pearce in Ravenous (1999)

-

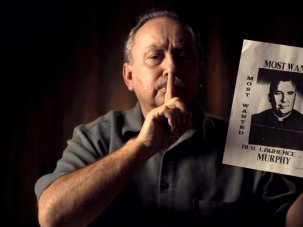

Karim Saleh in The Hamburg Cell (2004)