Sleep has been an integral part of the films of Apichatpong Weerasethakul since he began making them, but recently it has felt increasing central to the experience of viewing them as well. He introduced screenings of his last feature Cemetery of Splendour by stating that he didn’t mind people sleeping during them; and said the same (more understandably) ahead of the 16-hour, 36 film all-night Tate Modern retrospective of his work that took place a year later. This fascination with screen-slumber meets its logical endpoint at this year’s International Film Festival Rotterdam, where the director has created SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL, a site-specific temporary space – half-hotel, half-installation – where guests dream beneath an enormous projection screen.

SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL ran 25–29 January 2018 in the Postillion Convention Centre, Rotterdam as part of the International Film Festival Rotterdam.

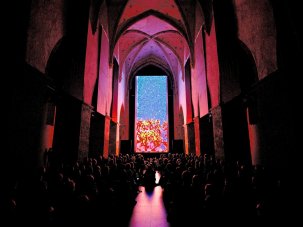

Inside, a cluster of beds suspended at varying heights – connected by a grid of elaborate scaffolding – form a canopy of nests. Arranged in a crescent, each bed faces towards the circular screen at the room’s end, mounted against the window so that the city lights flicker lambently behind it. Archive film, collected from a century of cinema and selected for its tranquility is projected silently and continuously, with the sound of tides overlain, lapping on a loop. In every nest, a bed and bed-side table with lamp, and various amenities including towels, slippers and a bottle of SLEEPCINEMAWATER. It’s a marvellous construction, inspired by an image from Sergei Eisenstein’s Strike (1925) where workers sit atop scaffold towers, their bodies carving shapely silhouettes against the geometric frames.

Credit: Matt Turner

Arriving after midnight, I settle down and start scribbling what I see and think. There’s no indication of the rules for this space. It’s a hostel, with shared sleeping arrangements and presumed conviviality; but also a cinema, with a focal point and the expectation of silence. Interpretations vary over what both of these environments mean separately, but by conflating them, presumably a new meaning is produced? I think about the hotel room seen in one of Apichatpong’s short films, Emerald (2008), a serene, silent space, haunted by floating particles (or are they feathers?) and friendly spectres; or the room in M Hotel (2011), a paradisal zone where two men take pictures of each other, playfully posing with pillows, safe and alone together.

I think also about his more recent projects such as Fireworks (Archives) (2014), where the projection occupies more than the screen, sending ghostly flickers dancing around the gallery space, illuminating dark corners and casting shadows over those in the room; or Fever Room (2016-), a project pushing further beyond the container of the frame, part performance, part projection, part three-dimensional light show. Is this room I’m in – where the viewers are part of the performance in a way, shadow-silhouettes cutting sleep-shapes in front of projected backdrops – an extension of these ideas? Is it an attempt to redefine what theatrical space might look like, or just a nice place to kip? Both, I suppose.

The screened sequences – none of which repeat across the installation’s five-day run – are unified by their serenity, a reverie of intoxicating miscellany. Much of the imagery I witness is images of nature, landscapes or aquatic scenes: trips through canals, rivers or oceans, scenes featuring sailors and steamboats, or simple stretches of endless, lulling waves, the effect of which is unsurprisingly hynotic. In between, a windmill, the underside of a blimp, two nuns folding clothes, light aircraft, a clock, a city seen from above, boys pillow-fighting, girls playing, many facial closeups, lots of people sleeping. At one point, an astounding sequence shows catamarans floating between blue triangle islands, at which my notes read: “this is SLEEPCINEMA, this is bliss.” I’m not sure what i mean, but I obviously feel something.

Credit: Matt Turner

Most of the footage is black-and-white or blue-tinted, but some is in colour, gentle green or yellow hues, mostly from sunsets or foliage. Around 2am, a series of scenes of particular beauty arrive, images of patterns of light cast over various objects. These shimmering visions, some of the most abstract imagery seen so far, could be from a Nathaniel Dorsky film. It makes me wonder about the authors of all these images, and of the role of the curator in creating dialogues and dissonances; but also what it means to curate at scale like this, and with such specific, soporific purpose? Maybe soon we will have dream curators?

At the next cut, a shot of clouds breaking over a landscape recalls Peter Hutton. Then some striking closeups that are very Carl Theodor Dreyer in composition; and cycles of flowers in bloom that look like lost Mary Field films. Is this sublime passage my reward for staying awake this long?

In a recent interview about these overnight projections, Apichatpong said that “in the night, one doesn’t need to interpret meanings but let the image and sound flow like a river. You cannot control it, just marvel,” and, as per, I’m guilty of thinking too much. It’s past 3am. I fill up my bottle. Is it still SLEEPCINEMAWATER if you replace it with tap water? How much should I watch? Is it strange that I’m seeking excitement from something designed to be somnolent? Would I be doing the experience a better service by letting sleep arrive, or is it revealing that I want to stay awake to absorb more?

Credit: Matt Turner

It is as these questions and others drift through my overactive subconscious that I fall into slumber. I awake often, each time to a new radiant plane of circular scenery, and each time having forgotten where I am, or even what I am. In half-sleep, the coruscating orb is not actually recognisable as a projection, but instead seems to be more like a portal, offering wondrous reflections of cinema’s past and the planet’s global present.

It turns out that I have a rapidly advancing viral infection, and my thoughts and dreams are more literally feverish than Apichatpong had perhaps intended. My body radiates hot and cold and my mind moves phantasmagorically through all manner of imagined scenarios both improbable and utterly mundane. I want to climb inside the circle, its glow beckons me.

Eventually, I crawl out of bed, scrawl the most delirious nonsense (sorry, Joe!) in the notebook left for guests to describe their experience, and stumble out in the cold streets of Rotterdam. I try to watch other things, but I’m stuck in what the SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL literature describes as Apichatpong’s “preferred plane of existence”. Either that or it’s the fever at work. I check into my next hotel, pass out and dream about the dreams I had before.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.