Amateurs in Space

The 37th Cambridge Film Festival ran 19-26 October 2017.

What’s Danish for sub judice? In the summer, megalomaniac inventor Peter Madsen was arrested after the journalist Kim Wall, having boarded Madsen’s private submarine to interview him, was found dead and dismembered, with multiple stab wounds. The prosecution team probably has enough to be getting on with, but Max Kestner’s documentary Amateurs in Space [weblink], completed before Wall’s murder, could serve as a character witness, presenting Madsen as a thin-skinned bully with a sinister streak visible from the moon. The film charts his attempt to build a manned space rocket – a vanity project, too expensive to be romantic – that falls apart, largely because of his egotism, in a welter of whiny emails. The sub appears, like the proverbial Chekhovian rifle, in the last shot.

The One-Eyed King

It was by no means the only instance of providential programming at this year’s Cambridge Film Festival. The Camera Catalonia strand, led by the British premiere of Marc Crehuet’s The One-Eyed King (El Rey Tuerto), on the day after the Spanish prime minister announced his intention to suspend Catalonia’s autonomy, could not have been more of-the-moment. Based on Crehuet’s stage play, The One-Eyed King is a four-handed black comedy in which a fascistic riot cop and a demonstrator whose eye he shot out find themselves at a dinner party arranged by their respective partners, old friends who have drifted apart along class lines. The cop comes round to the demonstrator’s trust-fund leftism – or at least the part about the global conspiracy of bankers – for a while, but the film ends with him looking out at the audience plaintively asking for answers.

In the Same Boat

There were plenty of those on offer in Rudy Gnutti’s documentary In the Same Boat [weblink], shown in the same strand, which begins with the visit of Cambridge economist John Maynard Keynes to Madrid in 1930, to deliver his talk Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren. Keynes famously forecast a future of “ever larger and larger classes and groups of people from whom problems of economic necessity have been practically removed” – if only (not so famously) the world population could be got under control, possibly under the rule of a technocratic elite. In the Same Boat, which largely consists of talking-head interviews with Keynes’s latter-day equivalents, sometimes brings to mind his hope, in the same essay, that “If economists could manage to get themselves thought of as humble, competent people, on a level with dentists, that would be splendid”, a prospect that seems as distant as any of his more ambitious predictions, but what is fascinating about both Catalan films is that the nationalist answer to the problems they anatomise simply does not come up.

King of the Belgians

In In the Same Boat, the economist Serge Latouche is heard to lament that in an age of globalisation “we still think on behalf of countries”, and perhaps it’s a passing phase; but decidedly not in the world of King of the Belgians [weblink], also making its British premiere. In this mockumentary by Peter Brosens and Jessica Woodworth, Wallonia secedes from the state in which much of the EU bureaucracy resides while its titular monarch is stranded in Istanbul, welcoming Turkey to the larger union. What follows is a Balkan odyssey during which the Scottish filmmaker who has been commissioned to make a puff-piece about the king reflects on the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s, and the king, learning that not even his closest advisors truly believe in his right to rule, begins to doubt his ability to keep his own country together. It was shown the day after Felipe VI made his strongest intervention yet in the Catalan crisis.

Revivals

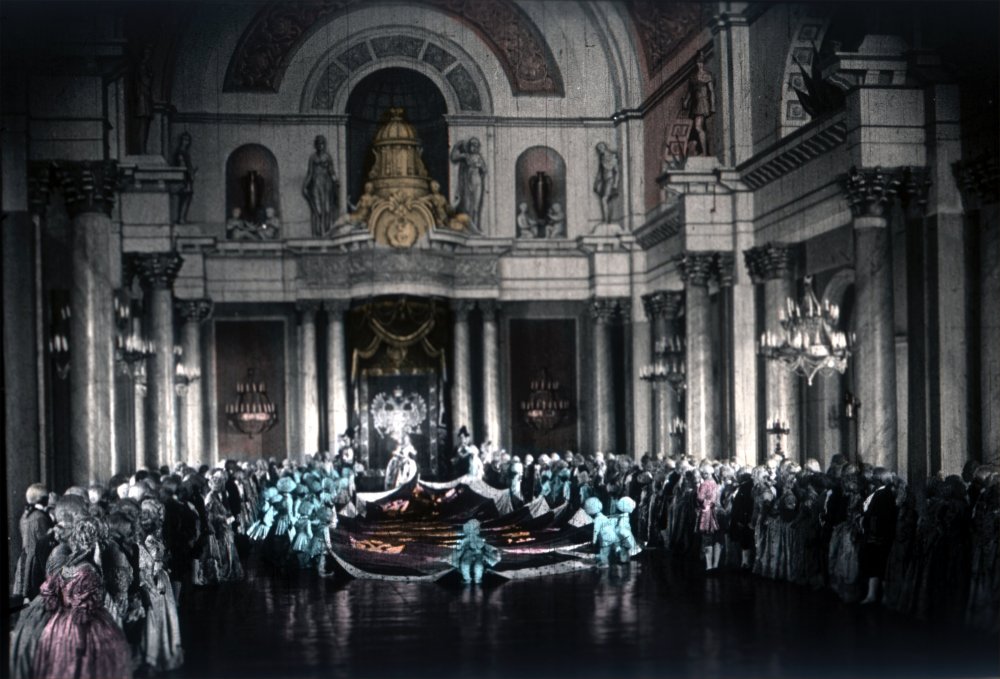

Casanova (1927)

There was a less urgent but nonetheless palpable sense of foreboding in the programme of Kinemacolor restorations from 1907-14, fresh from the LFF. The survival of these extraordinary specimens – a tiny proportion of the total number of Kinemacolor films that were produced – would seem to be down to the arbitrary workings of fate, so it’s all the more striking how so many of them feature men under arms. Even the touristic view of Venice in the last of the programme, L’Inaugurazione del campanile di San Marco (1912), includes a warship in the lagoon.

Venice in colour was also the highlight of the revival strand’s Casanova (1927), also up from London, but colour of a flagrantly artificial kind, painted on to the celluloid. Though absurdly long at two-and-a-half hours, Casanova is a fascinating case study for film theory – as played by Ivan Mosjoukine, the title character is said in an early title-card to be able to seduce women with a single look, and so the viewer becomes object of his gaze as well as its possessor. It’s a peculiarly interesting case because Mosjoukine was the guinea pig in the famous Kuleshov experiment, which was said to prove that audiences read into performers’ blank faces their own subjective reactions.

Virtual Reality

Easter Rising: Voice of a Rebel trailer

The festival’s Virtual Reality strand, mounted by Limina Immersive, was more thought-provoking still. What I ‘saw’ was Easter Rising: Voice of a Rebel (2016), which puts you in the Dublin GPO during the rebellion of the title, but the experience itself takes precedence, or does for a VR novice. What’s remarkable is how quickly and easily the suspension of disbelief kicks in, and this despite the programme’s deliberate and surprising rejection of the props of realism. Not only are the images not photo-realistic, but the carefully achieved spatio-temporal continuity which still underpins the majority of fiction films is also dispensed with. And yet the illusion works. This is partly down to ‘external’ circumstances – the low-lit room, the soft music, the simultaneous entry into the zone, which minimises one’s self-consciousness. It feels parochial to relate it all back to the cinema, though the importance of the screening space – its sanctity, even – is a lesson that might be learnt.

Microcinema

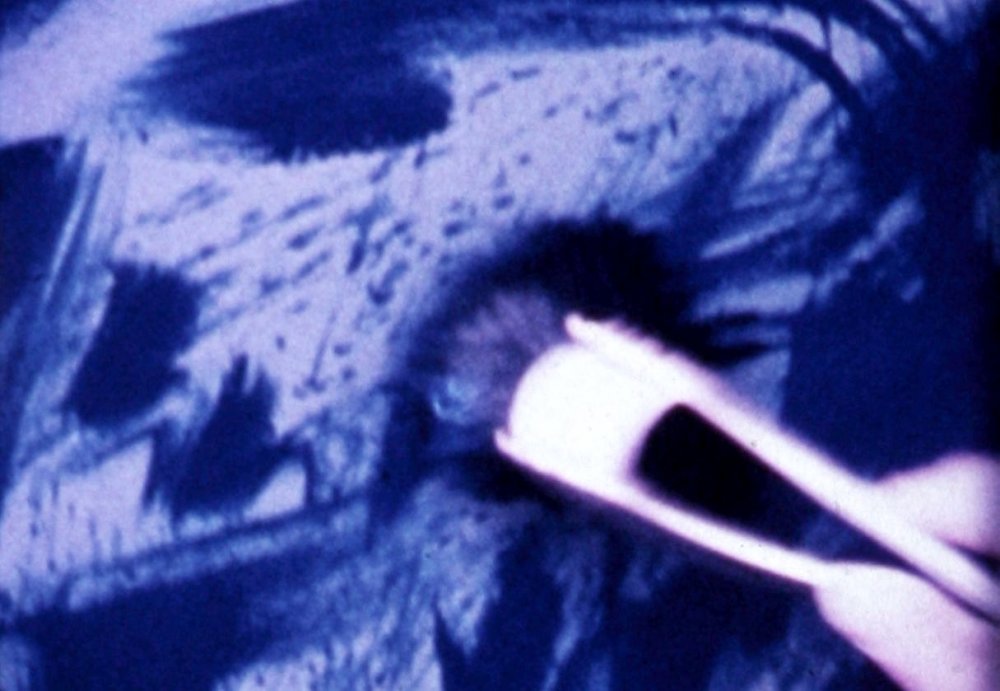

Blue on White Edges and Frames (1979)

The nearest equivalents to the VR experience were in the microcinema strand, which included Margaret Raspé’s Blue on White Edges and Frames (1979), for which Raspé constructed a camera-helmet with which to film herself painting, or rather to film the painting as it came into being. As ever, the ‘primitive’ and the marginal are the most reliable indicators of the future course of moving images; it’s characteristic of Cambridge that it managed to pack in all three along with plenty I haven’t mentioned. The festival suffers a little from its (temporal) proximity to London’s, but it is able to give its big films space: I am torn between regretting missing the Lynne Ramsay retrospective that led up to the closing-night film You Were Never Really Here, and cherishing having had the opportunity to see this astonishing film ‘cold’.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.