During the third of those 12 ‘tableaux’ which make up Jean-Luc Godard’s Vivre sa vie (1962), Nana, a young woman played by Anna Karina, visits a cinema where Carl Theodor Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928) is showing, and finds herself moved to tears while watching Joan being sentenced to death.

But what is it that makes Nana cry? Perhaps she identifies with Dreyer’s heroine, confronted, as Nana herself often is, by a domineering man. Perhaps she suddenly grasps how unrealistic her hopes of becoming an actress are, thus anticipating her descent into prostitution. Or perhaps she is reminded of her own mortality, suspecting (correctly, as it turns out) her life will be truncated as abruptly as Joan’s.

These explanations are hardly contradictory, Nana’s tears conceivably being linked to all three. Yet none of this quite accounts for that mood of sadness and loss which permeates the scene. As so often with Godard, our response is defined less by what happens to his characters than by the nature (technical, aesthetic, ideological) of the cinematic medium.

To better understand what is going on here, it might be useful to situate Vivre sa vie within a tradition of films in which people watch films, a tradition almost as old as cinema itself. In the surviving fragment of Robert W. Paul’s The Countryman and the Cinematograph (a title brought to my attention by Donatella Valente), we see a naive ‘yokel’ attending a cinematograph show, and responding with terror (as, supposedly, audiences once did) to a film depicting a train moving towards the camera. Even as early as 1901, moviegoers were assumed to be sophisticated enough to laugh at such behaviour, to feel superior to an individual so simple-minded that he cannot grasp the difference between life as it exists in the world and life as reproduced on the screen.

Yet Paul’s Countryman has a great deal in common with Godard’s Nana, who also perceives onscreen events as more reality than fiction. Vivre sa vie inspires tears rather than laughter because we, like Nana, know something the Countryman does not: that cinema has less to do with life than with death. Cocteau described cinema as “death at work”, while Louis Lumière, in 1895, dismissed it as “an invention without a future”, the possibility that these ‘quotations’ are apocryphal testifying to the mythic power of the idea they evoke. It is, then, hardly surprising that cinephilic discourses should frequently adopt a nostalgic tone, debates about the ‘death of cinema’ being conducted in terms which render celebration indistinguishable from lament.

The cinephile’s passion may be so intense that she will dream of infiltrating the screen, like Buster Keaton in Sherlock Jr. (1924). This infiltration takes place on a less literal level in Vivre sa vie, wherein the shot of Nana crying is followed by an intertitle reading “La mort”, folding Godard’s doomed protagonist into the silent film she is watching.

Goodbye Dragon Inn (2003)

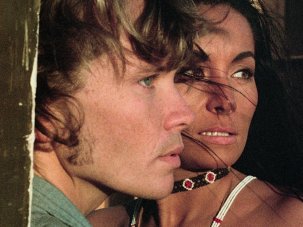

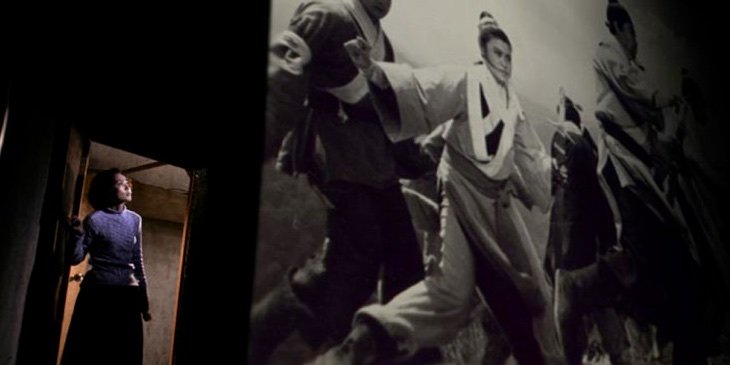

A comparable moment can be found in Tsai Ming-Liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003), set almost entirely in a dilapidated theatre running King Hu’s Dragon Inn (1966). At one point, the club-footed ticket-seller played by Chen Shiang-chyi pauses behind a screen displaying an image of Hu’s heroine Ms. Chu (Shangguan Lingfeng), and Tsai, eschewing his usual long-take technique, cuts rapidly back and forth between the crippled woman and the female warrior, suggesting a complex process of longing and identification in which the gap between life and art is both acknowledged and wished away.

The gesture through which the desires of Tsai’s ticket-seller are articulated is precisely the one that demonstrates their impossibility; longing to merge with the unlimited world of fantasy automatically summons up those physical limitations we yearn to escape from. This may explain why films depicting the act of film viewing tend to be curiously mournful.

Consider Terry Gilliam’s Twelve Monkeys (1995), in which James Cole (Bruce Willis) and Kathryn Railly (Madeleine Stowe) take refuge in a theatre hosting a “24 hour Hitchcock fest”. Upon encountering a sequence from Vertigo (1958) in which Judy/Madeleine (Kim Novak) contemplates temporality (“Here I was born, and there I died. It was only a moment for you. You took no notice”), Cole, whose problematic relationship to linear time is a central concern of the narrative, observes that “I think I’ve seen this movie before. When I was a kid, I saw it on TV… The movie never changes. It can’t. But every time you see it, it seems different. Because you’re different. You see different things.” This reference functions on multiple levels, not only suggesting a thematic connection between Twelve Monkeys and Vertigo, but also recalling Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1963), of which Gilliam’s film is a loose remake, and which itself alludes to precisely the same scene.

Twelve Monkeys (1995)

The audience addressed by Gilliam and Godard is a cinephile one, capable of identifying the film ‘inside’, and thus comprehending its relationship to the film ‘outside’. And if we perceive cinephilia – that desire to hold on to images that must inevitably be lost – as deeply rooted in our knowledge of mortality, such moments will become even more resonant. Works that use cinephilic references of this kind, imbricating characters in a film with characters in a film those characters are viewing, often do so under the sign of melancholia.

Consider Monica Bellucci crying like Nana/Karina during a screening of The Cranes Are Flying (1957) in Emir Kusturica’s On the Milky Road (2016). Or Bob Hoskins sadly watching They Live by Night (1946) on a hotel television in Neil Jordan’s Mona Lisa (1986). Or Jim McBride’s Breathless (1983), in which Richard Gere and Valérie Kaprisky make love behind the screen in a theatre where Gun Crazy (1950) is showing.

Or Monte Hellman’s Road to Nowhere (2010), wherein a Hellmanesque director scrutinises The Lady Eve (1941), The Seventh Seal (1957) and The Spirit of the Beehive (1973), ritualistically declaring each one a ‘masterpiece’. Or Wim Wenders’ Alice in the Cities (1974), in which Rüdiger Vogler comes across a broadcast of Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), destroying the television when a commercial intrudes. Or the teacher showing Dariush Mehrui’s The Cow (1969) to his restless students (who are more interested in filming him sleeping) in Asghar Farhadi’s The Salesman (2016).

Femme Fatale (2002)

Or the prostitutes in Walerian Borowczyk’s La Marge (1976) gathering around a TV to watch Pépé le Moko (1937). Or the drug deal conducted during a screening of Murnau’s Nosferatu in Abel Ferrara’s King of New York (1990). Or the partygoers projecting a reel of Metropolis (1927) in Jacques Rivette’s Paris Nous Appartient (1961). Or Rebecca Romijn, looking at Double Indemnity (1944), and seeing her reflection on the TV monitor, at the start of Brian De Palma’s Femme Fatale (2002).

Or any number of Pedro Almodóvar films, which refer to titles as varied as Splendor in the Grass (in What Have I Done to Deserve This?), Duel in the Sun (in Matador), Johnny Guitar (in Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown), Night of the Living Dead (in Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!), Losey’s The Prowler (in Kika), Buñuel’s The Criminal Life of Archibaldo de la Cruz (in Live Flesh), All About Eve (in All About My Mother), Mario Camus’s Esa Mujer (in Bad Education), Visconti’s Bellissima (in Volver) and Journey to Italy (in Broken Embraces).

All these filmmakers are aligning themselves with specific artistic traditions, connecting their own thematic concerns and stylistic tendencies with those of auteurs they admire. And in every case, the tone achieved is one of sorrow, anguish and (even when the circumstances of viewing are communal) isolation. There is a mystery here which has its roots at the heart of the cinematic experience, and perhaps at the heart of experience itself. To quote the tagline created by Michael Cimino to promote his film maudit Heaven’s Gate (1980), “What one loves about life are the things that fade”.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.