Here’s a tale of men and experience, sexuality and taste. And a story of the run-up to writing an article, rather than the article itself.

BFI Musicals! The Greatest Show on Screen runs at BFI Southbank, on BFI Player and at venues across the UK from October 2019 to January 2020.

I saw the recent musical film The Greatest Showman in a nearly empty afternoon multiplex screening, loved it and emailed Seamus McGarvey, the film’s cinematographer, to say so. He mentioned that the reviews were less enthusiastic, so I read them.

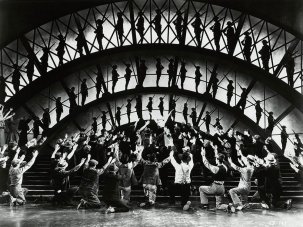

He was right, and I wasn’t surprised. Male reviewers in particular were dismissive. The film seemed too platitudinous to them, or pre-punk or bland. I considered writing about that here last month, but there’s nothing new in such reactions to musicals. There’s only one musical – Singin’ in the Rain (1951) – in Sight & Sound ’s poll of the greatest films of all time. The astonishing Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933) doesn’t appear, nor does Cabaret (1972). Nor does Rouben Mamoulian’s 1932 film Love Me Tonight, an influence on Edgar Wright’s Baby Driver (which itself is a musical in disguise).

None of the working-class men where I grew up liked movie musicals, a feeling they share with their contemporary polar opposites – educated, authenticity-focused grime or rooibos devotees. I love people in both these groups.

New York, New York (1977)

Years ago, I gave a lecture called Bobby Boys and Liza Lads: Masculinity, Identification and Scorsese’s New York, New York in which I tried to explore the gendered response to musicals. I wasn’t arguing that straight guys only like De Niro and gay ones like Minnelli, but I did want to mock a type of male, punk-informed taste which seemed scared of emotion and excess, especially female excess (Minnelli’s character’s suffering in the film). And to gender, add nation. Where I come from – Ireland and Scotland – understatement is not a virtue, but among Anglo-Saxon critics it often is.

Love Me Tonight (1932)

So the underappreciation of The Greatest Showman was familiar territory. Then four things happened. I talked to my film editor Timo Langer about this, and he said that he didn’t much like musicals – despite us sort of having made two: Stockholm My Love (2016), with Neneh Cherry, and Atomic (2015) with Mogwai. Esteemed film critic Mark Kermode, who disliked The Greatest Showman when he first saw it, rewatched it, liked it rather more, and apologised for his earlier denigration. Word of mouth meant that the film’s box office increased over the weeks of its release, rather than declining, which is the norm. And, today, I emailed my Sight & Sound editor, James Bell, suggesting that I write on why men don’t like musicals.

He emailed back saying, “Just raised that in the office here, and the response was, ‘But men DO like musicals!’” So I fired back: “I guess I move in different circles from the people in your office…” I immaturely wanted to communicate how much more in contact with atavistic movie tastes I am than the people in London who put this magazine together, most of whom I’ve not met, whose back stories and tastes I do not know, and who probably have seen more movies than I have. And so I was in a hall of mirrors. I was trying to say something about old-school male taste and genre prejudice and, beneath that, trying to identify a strain of arrogance in that taste but, in doing so, was I overstating its hegemony?

I wrote back to James at S&S. (Should I google him to see if he loves musicals? Maybe I’ll do it at the end of this article.) I said, “Your email makes me want to write about this even more – and to begin with this email exchange… Is that OK?” I was on the defensive a bit, but also spied a way into this subject – through a minor dispute, a misperception.

In the past, when a guy told me that they didn’t like movie musicals, I had five standard responses.

First, the majority of films made in the biggest film industry in the world – India’s – are musicals. How many of them have they seen?

Second, westerns in particular are often full of the sort of romanticism that people often reject in Hollywood musicals – so why the double standard?

Third, the performed and designed aspects of the more famous film musicals are often associated with camp; isn’t part of the rejection of the musical aesthetic an insecure attachment to old-school masculinity?

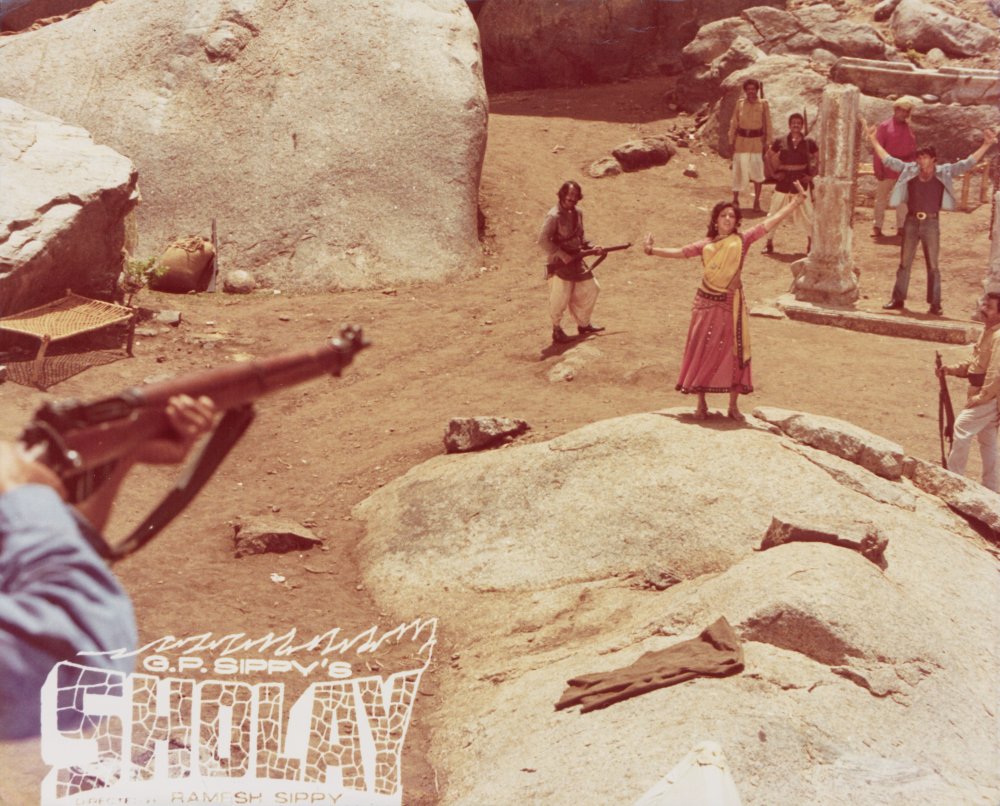

Sholay (1975)

My fourth challenge has always been to refer to the ‘dark’ musical numbers – in Ramesh Sippy’s Sholay (1975), a woman dances barefoot on broken glass; the Tomorrow Belongs to Me number in Cabaret; most of the songs on Pyaasa (1957) and Kaagaz ke phool (1959), etc. Don’t they show that musical doesn’t mean joyful?

And, finally – my most contentious point – within the critical sidelining of movie musicals, isn’t there a cult of the ‘dark’ which is too often associated with male angst?

Do these arguments still apply? In some ways, thankfully, no. Old-school masculinity, and its fascination with rage, are being downgraded, and younger men are less afraid of camp. And more female critics are being given – or are taking – the microphone, which should tone down the maleness of the canon.

But in one key way, not much has changed. Western critics, filmmakers and audiences are still mostly unaware of the vast majority of musicals, Indian musicals, their aesthetics, norms, themes, traditions and complexities. Until that changes, until we talk about Guru Dutt at the same time as we talk about Gene Kelly, we – women and men – cannot claim to know film musicals or fully understand them.

-

The 100 Greatest Films of All Time 2012

In our biggest ever film critics’ poll, the list of best movies ever made has a new top film, ending the 50-year reign of Citizen Kane.

Wednesday 1 August 2012

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.