Spoiler alert: this review reveals a plot twist

During the Q&A that followed the UK premiere of Toni Erdmann at the BFI London Film Festival, director Maren Ade expressed surprise at its inclusion in the comedy strand. She’d made a love film, not a laugh film, she insisted: a work that is bookended by two deaths and turns on the broken relationship between an increasingly desperate father and daughter. Make no bones about it, on first viewing, Toni Erdmann is as strange, delightful and dementedly funny as the hype has it. But repeat watching reveals a film that plays first as comedy, then as tragedy.

Germany/Austria/Romania/Monaco 2016

Certificate 15 162m 14s

Director Maren Ade

Cast

Ines Conradi Sandra Hüller

Winfried Conradi, ‘Toni Erdmann’ Peter Simonischek

Henneberg Michael Wittenborn

Gerald Thomas Loibl

Tim Trystan Pütter

Anca Ingrid Bisu

Tatjana Hadewych Minis

Steph Lucy Russell

Flavia Victoria Cocias

Dascalu Alexandru Papadopol

Natalja Viktoria Malektorovych

Annegret Ingrid Burkhard

Gerhard Jürg Löw

Renate Ruth Reinecke

[1.85:1]

Subtitles

UK release date 3 February 2017

Distributor Soda Pictures

► Trailer

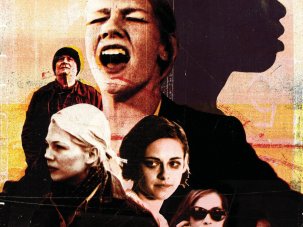

The humour is broad and situational, centred on the tension between highly strung career woman Ines Conradi’s focus on climbing the ladder at the management consultancy where she works and her father Winfried’s attempts to get her to lighten up. This he does by donning a wig and false teeth and, assuming the persona of lifestyle coach ‘Toni Erdmann’, effectively stalking Ines as she undertakes a series of professional engagements (Peter Simonischek is an extraordinarily good actor playing a mediocre one here, to great effect).

It’s a satisfyingly retro set-up, summoning such 80s/early-90s gems as The Secret of My Success, Big and Mrs Doubtfire. But where those films found comedy in the clash between personal happiness and the pursuit of the American Dream, Toni Erdmann is set against the backdrop of globalised Europe in up-and-coming Bucharest, an expat playground where shiny high-rise hotels and neon-lit malls stand back-to-back with shacks made of corrugated iron.

Winfried is baffled by the city’s venality. A child of the 60s, he’s been mocking the establishment for years, as an extended opening sequence makes clear. For the most part, his friends and family take his silliness in their stride, dismissing him with a gentle eye-roll. The only person shocked by his behaviour is his ex-wife, an earnest woman who lives in a tasteful, book-lined apartment.

Ines on the other hand keeps no books in the furnished apartment sourced by her put-upon assistant; there are few clothes in her closet; wine but no food in the fridge. Her sterile lifestyle is clearly a rejection of her parents’ liberal values, but at stake is power rather than money. Bullied at work by the laddish colleagues who describe her as “business nail varnish”, she fires people for a living, and takes no small pleasure in berating a spa attendant who falls below her exacting standards, or indeed a boyfriend who lets slip that he’s been indulging in locker-room talk about their sex life.

To Ines (played dead straight by dramatic actress Sandra Hüller), humour is one more weapon. From the first encounter we witness between father and daughter, she picks up his jokes and flings them back at him (“I’ve hired a substitute daughter,” he tells her. “Great. She can call you on your birthday so I don’t have to,” she deadpans back). She’s learned from the master, of course. Winfried may have the look of a dopey St Bernard, but just occasionally he bares his teeth. Their game of one-upmanship climaxes with him goading her into a glorious yet utterly humiliating rendition of Whitney Houston’s The Greatest Love of All that sends her running from the room.

Patrick Orth’s camerawork is mostly minimalist, the better to show off the astounding performances. Scenes often open on a character at rest, abiding with them as they move into action. Indeed, the real strength of Ade’s film lies in its pacing. Every sequence of the 162-minute running time feels significant, but then another comes along that feels even more so. The elisions are potent, too. A cut from Winfried mourning his dead dog to him alone in his garden at dusk to him waiting in Bucharest is particularly striking.

So there is liberation – genuine liberation – in the characters’ ostensible reconciliation towards the film’s end, as the camera, for the first time, takes flight for an extended tracking shot. But in keeping with the rest of the film, the scene is also weirdly ambivalent. Dressed in a traditional Bulgarian fur costume that covers him from head to toe, Winfried is not visibly himself, and remains entirely silent. Ines, meanwhile, is shadowed by a little girl who is completely, unabashedly enamoured with this great furry beast in a way that Ines herself is not, and perhaps can never be.

There is a bittersweet coda to the film that suggests something has changed between father and daughter in the aftermath of this event. But what has been lost that cannot be regained? When the laughter has faded, this is the question that lingers.

In the March 2017 issue of Sight & Sound

Infinite jest

German director Maren Ade’s unmissable comic drama Toni Erdmann presents a melancholy, beautifully drawn portrait of the relationship between an ambitious young businesswoman and her prankish father. Here the director discusses comedy, casting and why cliché is the enemy of complexity. By Isabel Stevens.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.