“People who suffer from depression often believe they’ve always felt this way. Like they’re trapped in a circle.”

UK 2016

Certificate 15 85m 10s

Director Gareth Tunley

Cast

Chris Tom Meeten

Jim Dan Skinner

Michael Coulson Rufus Jones

Kathleen Alice Lowe

Helen Fisher Niamh Cusack

Alexander Morland Geoff McGivern

Tommy Paul Kaye

Drez James Eyres Kenward

Danny Joshua Topp

Maria Rachel Stubbings

Gav Waen Shepherd

[2.35:1]

UK release date 4 August 2017 in cinemas

and on Blu-ray 4 September

Distributor Arrow Films

arrowfilms.co.uk/the-ghoul

► Trailer

So says psychotherapist Helen Fisher (Niamh Cusack) to her withdrawn, halting patient Chris (Tom Meeten). What Fisher does not realise is that Chris is an undercover police detective merely feigning mental illness to access the files on another of her patients, Michael Coulson (Rufus Jones). Helped by his investigative partner Jim (Dan Skinner) and psychological profiler Kathleen (Alice Lowe), Chris is trying to identify the killer in his latest case, a domestic double murder whose mysterious details do not add up. First, though, he must find the elusive Coulson, a ‘ghoul’ – someone unhealthily obsessed with crime scenes.

Or here is an alternative scenario: Chris is a chronic depressive who merely daydreams about being a detective on a case, and who regularly visits psychotherapist Fisher to mutter about his unhappiness and alienation. Kathleen is an old friend from university in Manchester whose obliviousness to Chris’s love for her is at the root of his problems. Jim is his best friend – and Kathleen’s long-term boyfriend. And Coulson is another patient of Fisher’s, whose particular condition makes a toxic mix with Chris’s.

Alice Lowe as Chris’s inamorata/psychological profiler Kathleen

In other words, writer-director Gareth Tunley (an actor in Ben Wheatley’s Down Terrace and Kill List) offers us not one but two diegetic routes through his feature debut The Ghoul, one paved in genre, the other in a more banal realism. While from early on it is clear – and meant to be clear – which is the master narrative and which the slave, the decision to present and interweave both through Chris’s addled perspective ensures that fantasy continues to contaminate the most grounded of sequences, and vice versa. London is shot by DP Benjamin Pritchard, often at low angle, as a disorienting labyrinth that engulfs and entraps Chris as he tries to find his way through a perplexing puzzle created by his own fugitive mind.

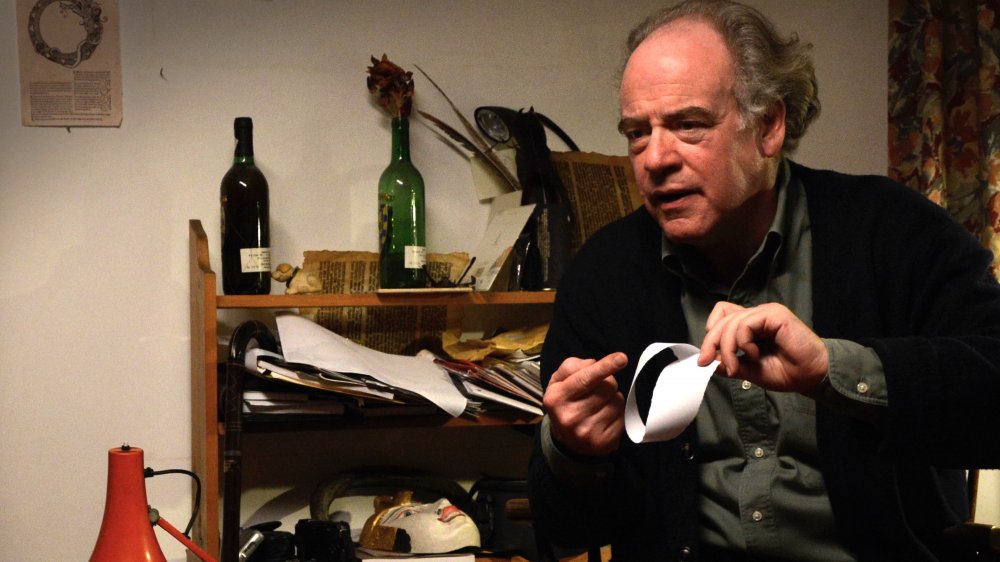

Geoff McGivern as psychotherapist Alexander Morland

When Fisher becomes ill, she entrusts her patient Chris (and Coulson) to the care of her semi-retired colleague and mentor Alexander Morland (Geoff McGivern). A disarmingly jovial and unconventional therapist who takes a ‘whatever works’ approach to his sessions (including metaphors of magic), Morland is the one who articulates, however obliquely, the film’s peculiar looping structure. For in discussing the paradoxical forms of the Klein bottle (“It’s got no inside or outside”), the ouroboros (a snake eating its own tails), ‘eternal return’ and the Möbius strip, he asks Chris to imagine an ant walking along a Möbian surface: “He’d end up back where he started, without ever crossing an edge, or turning back. Pretty weird for the ant.” This also perfectly describes the viewer’s experience of accompanying Chris on his own strange trip, in which reality and delusion wrap and warp into one another on parallel tracks.

There is a skew-whiff circularity to this lost highway, beginning and ending in the same place: the M1 leading both into London from the north, and back out again (the North Circular, which it crosses in either direction, might easily have served as a subtitle for The Ghoul). As Chris tries to navigate the dual carriageway of his brain, using two different hermeneutic maps that, enfolded together, reveal the nightmare of his damaged brain and of his life, he is both the bewildered ant and the titular ghoul, doomed to haunt a crime scene which he only ever half-understands but which keeps drawing him back in an eternal return.

Dan Skinner as Chris’s friend/partner Jim

Compensating for its small budget with big ideas and a bold method of storytelling, The Ghoul frontloads its big paradigm-shifting twist, allowing Tunley to concentrate his focus on the antihero’s spiralling descent into a madness that is never quite escapism. As the twinned plot gradually unravels along with Chris’s fracturing psyche, many members of the versatile cast are required to play double roles, while London itself is made an infernal character, its maze-like streets and towerscapes, canals and stairwells ensnaring a protagonist who neither belongs nor can leave.

Samuel Fuller’s Shock Corridor (1963), Jan Svankmajer’s Lunacy (2005), Martin Scorsese’s Shutter Island (2010) and Omer Fast’s Remainder (2015) are all evoked by the film’s heady mix of mental illness and imposture – and the result is an impressively melancholic, brain-bending tragedy whose convolutions are well worth revisiting through multiple circuits, whether in your spinning head or in subsequent viewings.

-

Sight & Sound: the August 2017 issue

Christopher Nolan on Dunkirk and real film, plus Sofia Coppola on The Beguiled, Jane Campion and Elisabeth Moss on Top of the Lake and Jean-Pierre...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.