from our July 2012 issue

Kosmos (2010)

If the films of Nuri Bilge Ceylan have taught us one thing, it’s that Turkey has very photogenic snow. That much is also evident in this most recent offering from his countryman Reha Erdem, which opens in a striking white-out landscape from which emerges a sole human figure, a mysterious stranger soon to change the lives of those he encounters in the nearby town. The location is Kars in north-eastern Turkey, near the closed border with Armenia – and incidentally the setting for Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk 2002 novel Snow. But Erdem’s film never mentions the place by name – just one indication of its retreat from realism into a celluloid world that actively resists definition.

Indeed, there’s a lot about Kosmos that’s hard to pin down. At first the eponymous protagonist seems to possess healing powers, as he brings a drowned child back from the dead. Later, though, those gifts seem on the wane as events take a tragic turn, and Sermet Yesil’s wide-eyed man of mystery also proves wary of becoming a healer-on-demand for the afflicted who start lining up outside his door.

What is it that drives this oddball character? Invited to stay in town by the father of the single mother whose boy he saved, he resists any encouragement to pay for his keep by actually working. Existing on a diet of tea and sugar lumps, he embarks on misadventures including a sexual assignation with a frustrated spinster schoolmistress, an attempt to wean an army captain’s ailing mother-in-law off her addiction to painkillers, and the formation of an intriguing bond with a kindred spirit – the aforementioned single mum. These two communicate via bird calls and animal noises, and even express their feelings for each other by leaving gravity behind, suggesting that each might be some sort of Ariel-like spirit in human form. Moreover, when they decide on secret names to codify their connection, he calls himself “Kosmos” and she calls herself “Neptün” – elemental choices that hint at realms unencumbered by everyday human borders.

Kosmos (2010)

What is clear is that Kosmos, wherever he’s come from, certainly doesn’t fit in with his current surroundings, where Erdem flags up a whole array of more worldly concerns: the soldiers whose booming offscreen artillery fire signals military manoeuvres going on nearby (presumably a show of strength directed at the Armenians on the other side); the rival political activists trying to whip up support for and against the opening of the border; even the four local brothers from different mothers locked in conflict over their inheritance. Yesil’s brilliantly attuned performance absolutely nails his character’s sheer otherworldliness, conveying through movement and vocalisation his animal and spiritual aspects, and delivering Kosmos’s gnomic pronouncements with enough conviction to maintain our curiosity. It’s no small task for any actor to manage all this, and he’s certainly one reason to see the film.

Kosmos sagely informs the men in the local café: “For him who is joined to all that is living, there is hope.” Elsewhere – as he insists there are no boundaries between rich and poor, man and beast – there’s a slippery relativism about his pearls of wisdom. Still, that phrase about “him who is joined to all that is living” seems the key line, since Erdem’s formal strategies bear out its import. Repeatedly he cuts to the cows facing their demise in the slaughterhouse, suggesting some mysterious empathy with the free-spirited protagonist, whose cries and yelps of affection for his beloved Neptün appear more bestial than human in origin. The military backdrop flags up ongoing questions of Turkish national self-definition, yet the suggestion is that we should all be looking at the bigger picture, a literally cosmic overview of pantheistic oneness outweighing such concerns about lines on a map.

On the soundtrack, electronic interference fizzes away like messages from some distant galaxy, as repeated shots of the town clock mark the passing hours, Erdem encouraging the viewer’s thoughts to stray outside the frame in space and time. Perhaps theresomething so grandiose about such notions that they become almost banal – different viewers will certainly take different positions on that; but Erdem’s film is never cut and dried about anything, pretty much leaving thematic and narrative completion to the viewer. That said, it’s a strikingly imaginative effort, a haunting and poetic film from a major talent who’s been gathering admirers on the international circuit since his breakthrough film Times and Winds (Bes vakit) back in 2006.

Kosmos (2010)

The product of a Parisian film school, Erdem works consistently with the brilliant Belgian cinematographer Florent Herry, and is open in his admiration of the likes of Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Tsai Ming-Liang; he’s clearly as internationalist in his outlook as, say, Kiarostami (with whom he shares a facility for exquisitely framed landscapes and gliding travelling shots). He is definitely his own man, however, in terms of playing out culturally specific Turkish concerns within a larger and broadly philosophical framework. Times and Winds, for instance, is a village rites-of-passage tale looking at how macho paternalism creates a cycle of repression and suffering; yet it intercuts those vignettes with startling tableaux where the children in the story (perhaps dead?) are weathered into the landscape itself, contrasting their momentary travails with the essential truths of geological time.

With Herry’s luxuriant images beautifying rural hardship, plus swathes of Arvo Pärt on the soundtrack, it’s no wonder that Times and Winds – for all its slightly capricious storytelling – captivated arthouse audiences. Sadly, rather fewer of them saw Erdem’s follow-up My Only Sunshine (Hayat Var, 2008 – though it is available on the online platform MUBI), another saga of growing up, this time by the Bosphorus, where the spectacular visuals of small fishing boats darting in and around passing tankers can’t quite mask a slim through-line (the adolescent heroine is no longer a child, not yet a woman) which barely sustains two hours of screen time. Again, the soundtrack bustles with offscreen aircraft and train noises hinting at bigger and better things beyond, yet the repetitive accretion of detail that worked in Times and Winds seemed more mannerist and exasperating second time around.

Then again, there are obvious risks involved in the way Erdem likes to build up his films in layers, returning again and again to his characters’ daily routines and ongoing dilemmas to build narratives through rhythm, patterning and contrast. If you look at Ceylan’s work, there’s always a sense of a linear trajectory, so that even if the end point is tellingly unresolved (see Once upon a Time in Anatolia), the journey towards meaning – towards trying to lock down a reading of reality within each film’s social environs – is of significance to the characters.

Kosmos (2010)

With Erdem, on the other hand, the three films of his creative maturity all operate in a cyclical manner, building up over time a rendering of a particular community or situation about which the filmmaker has things to say. However, the rhythm of returning to particular characters is often just about all that holds his stories together; you sense that Erdem is trying to free himself from the confines of linear plot development, yet the outcome is that there’s never quite enough impetus to drive his stories forward, and the challenge of finding an end to the cycle can also be a problem for him. Certainly, My Only Sunshine crumbles at the last, while the final reel of Kosmos is surely its relative weakness too.

Still, there’s no question throughout his films that you’re engaging with a distinctive sensibility trying to find new ways to tell stories – which is part of what makes his output so striking. Kosmos is undoubtedly highly personal, and not a little puzzling at times, yet there’s more to it than beguiling visuals and captivating exoticism. It’s rich and rewarding because, in more ways than one, Erdem is reaching for the stars.

Kosmos is on selected UK release from 15 June. Reha Erdem talks about the mystique of his protagonist and his location on page 53 of the July 2012 issue of Sight & Sound.

-

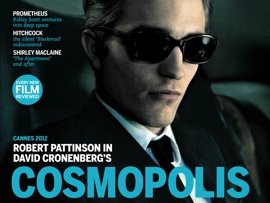

Sight & Sound: the July 2012 issue

Thursday 21 June 2012

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.