Even as the improved representation of disadvantaged and less visible groups in media and entertainment evolves from a demand into an expectation, little focus seems yet to have fallen on the ways in which elderly people are depicted. The presentation of old age as a curse or a punishment remains prevalent, as does the portrayal of old people as infantile, monstrous or burdensome. Meanwhile, the idea of youth as the best human state, and young people inherently fascinating, is rather more durable than most of the work that very young people produce.

Turkey/USA 2018

Certificate 18 80 mins approx

Director Shevaun Mizrahi

UK release date 17 August 2018

Distributor ICA Cinema

ica.art

► Trailer

Regrettable though it may be in terms of lives undervalued and stories untold, it’s not hard to understand why such a bias exists. Sexual desirability is linked to perceived fecundity; health problems multiply in old age, while opportunities for self-reinvention dwindle; frailty and incapacitation are distressing to look upon. And regardless of our own stage of life, old age in others is unsettling because of the many ways in which it might yet challenge us. At our oldest, will we still be ourselves? Will we be in pain? Will we be wise and warm, or bitter? And will we be alone?

This film takes a simple approach to the subject of old age, and achieves an unusually warm, complex and illuminating picture of some of its myriad manifestations. Turkish-American director Shevaun Mizrahi was studying cinematography at NYU and working as an assistant to the US cinematographer Ed Lachman when she began filming informal portraits of the residents of a care home in her father’s native Istanbul, where she was volunteering. She shot the same individuals and their environment over seven years.

The resulting vignettes are funny, startling and touching. They offer an extraordinary account of what continues to matter to people and what falls away, and of the tenacity of some aspects of personality and the fragility of others. A woman tries to get into a lift that doesn’t have space for her walking frame; it’s “just for people”, she notes as she retreats, prompting another resident to cry in protest, “Aren’t you a person yourself? You are a person!”

Mizrahi has picked out many such lovely moments of human connectedness and linguistic play. “Do you believe in life after life?” a man asks his friend. “Yes,” comes the response, “we will all turn into soil one day.” Later, the same pair discuss the head injury that one of them has sustained. “I am very sad for you, I will pray for you,” says one. “No need for that,” responds the stoical injured party, “God is on top of it.”

If an excess of this sort of material would have risked cutesiness, it’s instead skilfully balanced with interviews that go to strange, sad and dark places, and with purely visual moments of dreamlike intensity. (It’s apparent that Mizrahi admires Ulrich Seidl – whose Paradise trilogy she worked on with Lachman – though on this evidence her worldview is rather more benign.)

In one interview, a woman recalls in vivid, painful detail the abuses suffered by her Armenian family under Turkish forces during her childhood; still afraid of the consequences of speaking out, she asks that her real name not be used. Elsewhere, a photographer surrounded by his camera parts explains with poignant good humour that he is going blind. His tic of repeating phrases turns his speech into a song: “There’s nothing they can do, there’s nothing, there’s nothing, I don’t know, I don’t know, there’s nothing, there’s nothing.” A one-time Lothario, more fluent than the photographer but prone to his own brand of repetition, reminisces about sex parties (which, for the record, he doesn’t favour, preferring “maximum two girls and me”).

Each of these conversations contains multitudes. The Armenian woman looks back not only at the oppression of her people, but also at her own work as a nanny. Her pain at being parted from one particular child, who would now be an old woman herself, remains fresh, as does her dislike of a mother she perceived to be neglectful. But if the past is close at hand, so too is oblivion. “I slept, didn’t I?” she says, after a long moment of quiet. “I’m sorry, I drop like that.”

As the photographer talks fitfully about his earlier life and current state of health, Mizrahi’s camera finds mounted on the wall a picture of him in his youth: the juxtaposition of the debonair, flashy younger man and his elderly incarnation, at once the same person and not, is deeply affecting.

And then there’s the Lothario, who thinks Humbert Humbert gets a rough deal in Lolita (“He loves her like a father”), reads pages of self-penned erotica to the camera and, in perhaps the film’s most disarming moment, makes a proposal of marriage to Mizrahi. “I feel good with you,” he tells her. “You’re nice with me. I don’t get bored with you.”

This moment lends itself to several interpretations, which are in themselves revealing of complicated and contradictory ideas about ageing, gender and the act of filmmaking. On the most obvious level, it’s another lovely bit of character detail, telling us about the man’s self-image and preoccupations. Reduced to a circumscribed institutional existence after a richly chequered life, he is thrilled and frustrated by the focused attention of the sort of woman who might once have seen him as a fitting partner. His old self flickers forth and tries to seduce her, and although he adds caveats about her likely objections, it’s clear that he feels he has a lot to offer her.

To some, the introduction of sex into the relationship between Mizrahi and her subject will stand as further disheartening evidence of the difficulty that female filmmakers face in simply getting on with their jobs: harassment is so endemic that it even occurs on camera. But the power imbalance here can also be read the other way, as a filmmaker choosing to expose a vulnerable subject to mockery. The deluded dotard who overestimates his romantic appeal to a much younger woman is, after all, one of the oldest jokes in the book…

Other viewers may regard the scene as a subtle comment on the forced, false or temporary intimacy that can develop between documentarians and their subjects, and the ethical questions this raises – Little Edie Beale’s designs on Albert Maysles in Grey Gardens (1975) spring to mind, for instance, as do the behind-the-scenes relationships of Sex: The Annabel Chong Story (1999), The Staircase (2004) and Risk (2016), and the startling interaction between subject and director in A Family Affair (2015).

Whichever way we read it, the proposal alters the film’s atmosphere by making the director inescapably present. Although Distant Constellation has hitherto been hands-off in terms of its presentation – still, meditative shots, no clear narrative, no voiceover – Mizrahi’s sudden repositioning as love interest reminds us not only that what we are watching is her construction, but also that her presence is affecting her interviewees and their testimonies.

And the puncturing of the fourth wall also makes a more general point: that we are all involved in this story, the story of ageing. Whether we mock, moralise about or sympathise with its effects on other people, and whatever we make of its portrayal in the media, none of us can stay distant from it for long. Yet it’s characteristic of the restless verve and spirit of Mizrahi’s filmmaking that she doesn’t let his piece settle into fatalism or sentimentality. Around the nursing home as she filmed, construction work was taking place; rather than present this process as some regrettable incursion of ugly modernity on sweet old age, Mizrahi treats it with the same good-humoured interest she applies to the residents. Time moves on, goes the gentle suggestion; old buildings give way, just as old people must, to the new.

-

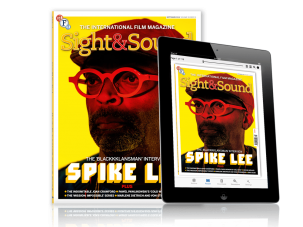

Sight & Sound: the September 2018 issue

Spike Lee: the BlacKkKlansman interview; the indomitable Joan Crawford; Pawel Pawlikowski’s Cold War; Mark Cousin’s on the drawings and...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.