Web exclusive

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

Shortly before the beginning of the 2011 Berlin Film Festival, a copy of a documentary about the jailed Russian oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky, a staunch opponent of his country’s current prime minister Vladimir Putin, was stolen from office of the film’s German director Cyril Tuschi. Given that the latter had got used to being shadowed by Russian secret service agents over the five years he spent filming of Khodorkovsky, it seemed entirely plausible that the theft had been politically motivated. On police advice the filmmaker moved out of both his home and his office.

Yet speaking this January on a visit to London to watch Man in the Middle, the play about WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange which he hopes will be the subject of his next film, Tuschi reveals that the German police had arrested and charged two men in connection with the robbery.

“It turns out that it was a couple of idiots, who were stealing Apple computers, rather than being the work of the Russian secret services,” he says. “It’s funny; I spoke to Guardian journalist Luke Harding [the author of Mafia State], who was intimidated by the FSB [the successor to the KGB]. His kids were harassed at school. I wondered why nothing more serious happened to me and my family. My only explanation is that I’m German and Putin loves Germans, whereas he dislikes the British for sheltering dissidents like Boris Berezovsky and Alexander Litvinenko.”

The British release of Khodorkovsky couldn’t be more topical, with Russian presidential elections on 4 March. In their build-up, tens of thousands of white ribbon-sporting demonstrators have taken to the streets in anti-Putin and pro-democracy protests, drawing comparisons with the Arab Spring.

Tuschi himself has detected a shift in attitudes within Russia since December, coincidentally the month in which his film received its premiere in Moscow. “I really believe that the Russian people are losing their long-inherited fear,” he says. “They laugh when they see the footage of Putin in the film. Russian exiles in the USA and Israel don’t believe me when I say that. Putin built and reigned his empire on fear, and I believe we’ll see it vanish in the near future.”

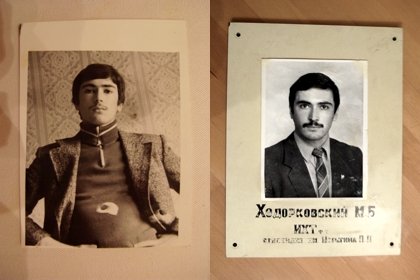

Portraits of the tycoon as a young man

Unlike many of the campaigning documentaries that receive cinematic distribution in the UK, Khodorkovsky is designed to be watched on the big screen. Charting its subject’s journey from devoted young Communist to super-wealthy oil magnate through the purchase of Yukos Oil, then arrest and imprisonment in Siberia, it’s filmed in the ’Scope format and incorporates animated sequences, narration by Jean-Marc Barr, spoken extracts from Khodorkovsky’s letters and Arvo Part’s Los Angeles symphony on the soundtrack.

Fittingly, the film beings with a wide shot of the forbidding Siberian winter landscape. “I didn’t want to bore myself stylistically,” explains Tuschi, whose background lies in fiction films. “I’m attracted to larger-than-life, fairytale characters and didn’t want to make a film that was just a succession of talking heads. We didn’t even expect to be able to interview Khodorkovsky himself because he was in jail. In the end I got ten minutes with him while he was caged during his second trial in 2009. After two minutes I dropped the translation to save time. A guard was counting down every minute with his pistol on my shoulder.”

Before making the film, Tuschi knew next to nothing about Khodorkovsky, although the director’s great grandfather was an industrialist who fled St Petersburg during the October 1917 Revolution. Visiting a film festival at the Siberian oil-boom town of Khanty-Mansiysk with his previous film Slight Changes in Temperature and Mind, Tuschi had learnt that Khodorkovsky had been dramatically arrested by secret service operatives in 2003 and charged with tax evasion.

“I started writing an exposé for a fictional treatment of this story”, he explains, “and got my cameraman to start shooting a bit on an HD camera in Siberia. But I gave up on the screenplay when I realised that the reality was so much stranger than I had anticipated. In the first year of filming nobody wanted to speak to me. Khodorkovsky’s world seemed so sealed off. I think his friends thought I might be working for Putin. You have to remember that 2006 was the peak of wealth in Russia. Moscow was the city with the most billionaires in the world. People wanted to know why I was making a film about a so-called ‘loser’ in prison. Why didn’t I do something about success?”

Director Tuschi (left); Khodorkovsky ally Alexander Osovtsov (right)

In incorporating the obstacles to filming into the film itself, Tuschi appears to be taking a leaf from Nick Broomfield’s self-reflexive playbook, although he declares himself unfamiliar with the English documentarian’s work. And to those who have alleged a pro-Khodorkovsky bias in the film, he insists that his attempts to speak to a wider range of sources were rebuffed. “Sometimes I used my real name, sometimes I came up with false identities. Sometimes I even didn’t let on to some what the film’s title was. But a lot of people were afraid of critical questions.”

One particular sequence in Khodorkovsky, in which Khodorkovsky supporter Alexander Osovtsov – the former manager of Khodorkovsky’s Open Russia Foundation – is interviewed while feeding a baby hippopotamus, seems guaranteed to win the approval of Werner Herzog. “That guy owns the only private zoo in Russia,” recalls Tuschi. “He doesn’t let people in for money – he just invites friends around. He’s got something like 50 horses, 100 dogs, snakes, kangaroos and eagles. He was a university dean and a member of the Jewish Russian congress. I thought his anecdote about feeding avocados illustrated something about the power of the Russian state. He’s moved the whole zoo now from Moscow to Bratislava, having spent thousands of dollars bribing the border guards to get the animals over.”

The question that overhangs the film is why Khodorkovsky spurned various opportunities to flee into exile in 2003 and avoid arrest. Various interviewees pay tribute to the man’s strategic intelligence, bracketing him alongside the chess grandmaster Gary Kasparov, another vocal enemy of Putin. Did Khodorkovsky offer himself up to the authorities as part of a long-term plan to earn redemption in the eyes of the Russian people, who’d hitherto regarded him as a predatory capitalist? A former adviser, the libertarian Christian Michel, talks of the oligarch sacrificing his queen in order to triumph in the end game.

Tuschi himself agrees with these chess-playing analogies. “He seems to think eight steps ahead of other people. So when he gets arrested, you wonder what the purpose of the move is. I don’t want to romanticise him too much – he’s very stubborn and in some ways has a very boring personality. What I find interesting is that nine years in prison has made this man who trained as a scientist very well-read in literature and philosophy. But as long as Putin stays in power, I think he will remain in prison.”

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.