British-born film director Bernard Rose has long been an advocate and admirer of Nicolas Roeg, and collaborated with him on various projects in the 1980s. After training as an assistant to Jim Henson and at the National Film and Television School, Rose began making television dramas and rock videos before directing features, most notably Paperhouse (1988), Candyman (1992) and Immortal Beloved (1992). More recently he has shot a cycle of low-budget dramas himself on digital video, all drawn from short stories by Tolstoy, beginning with Ivansxtc. (2000), while his latest film, Frankenstein, won top prize at the Brussels International Fantastic Film Festival in April 2015.

This interview took place in Los Angeles in the summer of 2014 for inclusion in David Thompson’s new Arena film, Nicolas Roeg – It’s About Time.

Bernard Rose interviewed in the BBC Arena programme Nicolas Roeg: It’s About Time (2015)

When did you first encounter a Nicolas Roeg film?

Arena: Nicolas Roeg – It’s About Time is broadcast on BBC4 at 10pm on 28 June 2015.

It was when I went to see a screening of Don’t Look Now (1973) on its first run, in a double bill with The Wicker Man (1973). I liked horror films and there was a buzz about both these films. I saw them one after the other, and was completely blown away by Don’t Look Now. It was poetic, terrifying, moving, emotional, believable. It was and still is, my favourite horror film.

And then I remember watching The Wicker Man, and when horror fans say, “Oh, isn’t The Wicker Man great?” I go, “It’s alright”, because after seeing Don’t Look Now, The Wicker Man looked just so dull and flat. What Don’t Look Now has that The Wicker Man doesn’t is a complete mastery of cinema. Don’t Look Now is almost a silent movie, a brilliant, coherent, original and fantastic film that has an enormous emotional impact.

After seeing it I was very interested in seeking out anything by Nic Roeg. I remember reading about The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), which was in production a couple of years later. I rushed to see it when it first came out, and I loved it too. It’s a richer, more complex film than Don’t Look Now, but it’s every bit as much a masterpiece. After that I saw every single thing Nic did. But definitely I remember seeing those two films when they first appeared in the cinema, and they had a huge impact.

What were the distinctive elements in Don’t Look Now that most impressed you?

The thing about Nic Roeg’s cinema is that its subject matter is always psychic phenomena. A lot of people have credited Nic with the invention of cross-cutting, as if this was some great new invention. Of course there’s cross-cutting in D.W. Griffith, but cross-cutting traditionally in a film is two things happening in parallel that are played off against each other. Even in, say, Intolerance, where something’s happening in ancient Babylon and something’s happening in 1916 America and something’s happening in sixteenth-century France, these events are intercut with each other in a way that they very directly mirror and run parallel to each other.

Don’t Look Now (1973)

The idea that Nic invented that is nonsense, but what Nic does is something much more interesting. He connects the shots on a psychic basis. Look at the opening sequence of Don’t Look Now. Everyone remembers it as happening in Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie’s house, while the children are outside playing by a pond. In the middle of that sequence he’s looking at slides from the church in Venice which he’s going to renovate. But right before the film even gets going there’s a shot of the light reflecting through a louvered blind in a hotel room, and it’s completely out of context. But if you look you’ll see that it’s actually the window of the hotel room where they’re staying much later in the film.

So why is this shot of the hotel room just sitting there? To me it’s because there’s a psychic connection between what’s going to happen in the hotel and what’s happening by the pond. He’s laying clues. He’s saying that, if there is a psychic connection between things, it’s not going to happen dramatically. You’re not going suddenly to have this vision of a child dying. It’s going to be this vision of the light playing on a window.

There’s something very poetic and wonderful about the way he throws in things which seem completely random like that, but they’re not random. They’re very thought through and beautifully placed. Don’t Look Now is so perfect, the way the whole thing builds to the sequence at the end where Donald Sutherland is dying. And suddenly his life flashes in front of his eyes. And at that point the movie makes sense, and it makes sense in retrospect.

Were you also impressed by the sex scene?

Everybody remembers the sex scene between Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland. You could say, “Well, why is the scene so memorable even today, when there’s a million more explicit things on the internet?” The reason is because the scene shows something you never see in a film. You never see a sex scene between a married couple. Never. It’s always between people having an affair, or meeting for the first time.

Don’t Look Now (1973)

So why does he spend all that time with them having sex in the middle of the film? You could say, “It’s because she’s recovering emotionally from the loss of her daughter”, or “She’s feeling sexual again because the psychic told her the daughter is alright”. That’s not why he has that scene in there. He only reveals the reason why he filmed that scene in the final sequence, when Donald Sutherland is dying. He cuts from one shot of him making love to Julie Christie back to her on the funeral barge coming round the corner. One of the most incredible, dynamic endings in any film ever.

You go, “Well, what is the point of that?” The point is, of course, that she’s pregnant. It’s so subtle and it’s so circular. She’s pregnant. And that’s why there’s the shot of the window with the water at the beginning of the film. It’s her looking, or him looking at the water. It’s from the sequence where they’re making love in the bedroom. It’s so elegant and it’s so hidden. That’s what’s so moving at the ending. Yes, it’s tragic and it’s terrible, the child’s dead and he’s been murdered, but there’s something of him that lived on. And it’s in her.

For Nic, it’s always about that; that’s why his films are very sexual, especially in the later films like Puffball (2006), where it’s even more explicit. For Nic, sex is about procreation as much as it’s about pleasure. That’s the whole conundrum of how it all fits together like a Rubik’s Cube in Don’t Look Now. When it was first seen, people would say, “Oh, if you look at the cutting style, it’s weird and out there.” Now if you look at it, it’s actually really simple and direct. It’s just non-verbal.

One of my pet hates at the moment is people saying how wonderful television is nowadays. And they go on and on, and name all of these big shows. And I go, “Yeah, I’m really glad you enjoy them. But…” And one of the things they say is how cinematic they are. But calling something cinematic is not to be confused with moving the camera.

Really what they should say about those shows is that they use grip equipment. What happens on those shows – which is what happens on all television – is illustrated radio. People don’t watch television by looking at it all the time, they’re looking up, they’re looking down, they’re checking their phone, they’re eating their dinner. So they need to have all the information verbally, and all those shows still adhere to that.

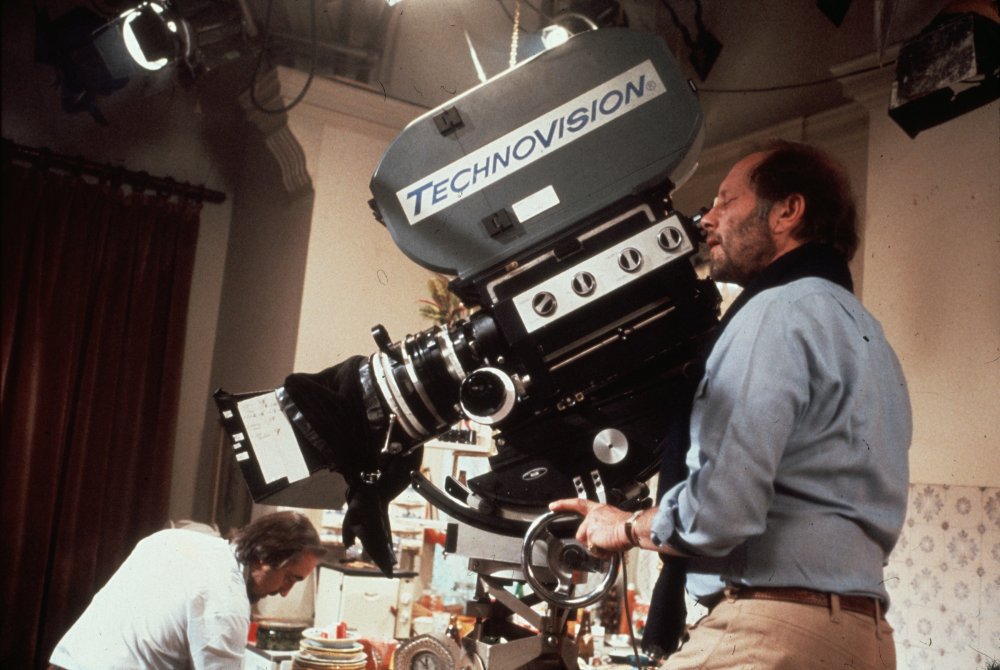

Nicolas Roeg directing Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie on the set of Don’t Look Now (1973)

If you are not paying full attention to one of Nic’s films, you do not know what’s going on, because very little information is carried in the dialogue. In that sense Nic’s films have that direct line to silent cinema. I love it when a film tells you its story through pictures and never has anyone say it. If it were Game of Thrones, at the end the woman would have turned to Julie Christie and said, “Are you feeling okay?” “I’m feeling a little sick this morning, I hope I’m not pregnant.” That’s how it would have been in Breaking Bad too.

But if you look and see her, you understand that’s what her husband was psychic about. Nic is trying to talk about things which can’t be spoken. If you speak about them they sound trite, and you reject them as much as Donald Sutherland rejects everything he knows to be true in that film. He’s the skeptic who says throughout the film, “No, this is bullshit, these are stupid old women, they’re taking advantage of you.” And of course what he’s always talking about is that he’s the one with the premonition, the one who’s seeing these dreadful visions and the one who’s in total denial. If you verbalise these things, either you make them either very trite or unbelievable. Whereas if you show them and let the audience experience them, you get the sense of the thing that is out there.

That’s the major appeal of the horror genre, that we can experience the supernatural in a much more concrete form than most people experience it in real life. The greatest horror films do that: Don’t Look Now, The Shining, Rosemary’s Baby, The Exorcist. That’s why those films are loved and will always be loved, because they have that element of spirituality that’s very concretely experienced by the audience. Don’t Look Now is the best film about psychic phenomena ever, because it’s dealt with in that non-verbal, cinematic way.

This is certainly true of Walkabout and The Man Who Fell to Earth.

In his book The World Is Ever Changing, Nic talks about how art can investigate phenomena just as thoroughly as science. A lot of what he does is a demonstration of that. In the book he gave an example when the cow is shot in Walkabout, and he reverses the film and makes it stand up again. And it’s a very interesting non-comedic use of reversing things. Once people were able to run films backwards on a flatbed, people’s first instinct was normally to laugh. People who have never seen it before find it monumentally funny.

But what Nic spotted in that is that this is what it would actually look like if time ran backwards, this is taking these individual segments of time and reversing them. Tarkovsky talked a lot about how film is the only medium which can deal with time in those ways. Nowadays there are cameras like the Phantom which shoot 2,000 frames a second. It makes a 2½ second event last ten minutes. So if you shoot something with it, you don’t really see it, you’re looking at things that you, as a human watching in real time, couldn’t perceive.

It starts to make you aware of how little of the universe we actually see. That’s where Nic works, and that’s what The Man Who Fell to Earth brilliantly and beautifully demonstrates, just how little of the universe we see. The moment we are exposed to more of it, our next reaction is to numb it with drugs and alcohol. The Man Who Fell to Earth is a brilliant and very tragic movie because it’s as much about alcoholism as it is about science fiction. It’s one of the best movies I’ve ever seen about alcoholism. You really see people drinking in that film, and you see it destroy them, piece by piece. It’s very interestingly done. And that’s how the film ends – Bowie’s just too drunk to complain any more.

The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

In retrospect, what Nic was responding to was that he was operating in an era of great freedom and expression, the late 60s and 70s, when people thought that art was going to be the answer, when rock stars thought they could create revolutions, when people in the cinema really believed in what they were doing. A good example is Apocalypse Now. Coppola went out and produced Apocalypse Now, and now our image of the Vietnam War comes from that movie. Before Apocalypse Now, you could have an argument about whether the Vietnam War was won or lost, but after Apocalypse Now, it was lost and that was it. That’s why in the 80s, films like that had to be stopped. Within five years they were making Top Gun and everything was okay again.

The Man Who Fell to Earth is about visionaries who know things and can see things, who are experimenting in the real margins of things, and how they will be destroyed, anaesthetised, drugged and numbed until they’re just completely neutered. As a metaphor for what happened, it’s horrifyingly true. Who knows if Bowie has good motives in the film? He’s very ambiguous. There’s a wonderful exchange when Doctor Bryce, the Rip Torn character, says, “Are you angry?” And Bowie looks confused, and he says, “I can’t be.” He doesn’t mean he is or he isn’t. It’s not part of his physical makeup. He can’t be angry but he can be drunk. There’s something very profound about that, that he just numbs himself. I love that film too. It’s very melancholy. You could say that there’s a lot of hope in Don’t Look Now, perversely, but there isn’t in The Man Who Fell to Earth. Its ending is absolutely a downer.

Time is handled in a very challenging way in that film.

One of the things Nic is experimenting with is, as it were, the psychological arrow of time, that what we adhere to isn’t necessarily concrete. There’s a sequence in The Man Who Fell to Earth when Bowie’s riding in the car and he suddenly sees the people in the dust bowl, and they see him back, it’s as if he’s suddenly slipped from one era to another, but nobody else can. It’s the idea that things coexist. There’s a scene in Walkabout where the boy suddenly sees camels from the original British occupation of Australia, just walking across the frame for no reason. There is that sense of all these things from the past existing in the present and the future.

One of the nice things about film is that you can obliterate time. You can reverse or wind the film backwards. You can slow it down, you can speed it up. You can obliterate hundreds of years with a cut. The first special effect ever was the jump cut, which Méliès discovered. All frames are jump cut from one to the other, because there is no relationship between one picture and the next. In that sense you can put them in any order, and Nic has always understood that. He’s not just playing with it, he’s investigating it.

That’s why his temporal games are always done on some sort of psychic basis. One character can always see more. Then you have to ask Nic the question, has he had any of those experiences? If he answered honestly, he’d say that he has. He’s very open to looking at things from a mysterious point of view. That’s why the films feel so alive to us now, and that they don’t feel contrived.

How do you place Eureka (1983) among his films?

When people saw Eureka it made them angry, and they stomped on it. It has that feel about it, which always makes me more interested in a film. And it’s a wonderful movie, and it’s full of movie stars too, so you wonder why the hell was it stomped on? It’s difficult to know.

You could say that again its message is against what they want to hear. It was made at that very key time, just after Apocalypse Now, around the time of Heaven’s Gate, just before the studios decided to take control again and started making Flashdance and An Officer and a Gentleman. Around 1980, someone obviously very high up said “We’ve got to stop this because we’re losing this huge psychic propaganda tool, the cinema. People are doing what the hell they want, it can’t go on.”

Eureka (1982)

Look at Eureka. It’s a film that says being rich is horrible, that success leads to disaster. It’s everything that’s not the dream. Even if you look at The Godfather, they’re all trying desperately to become the head of the mafia. Eureka is much more honest. It’s saying, here’s this guy, there was a moment in his life when he was up there and he was really risking himself and everything to make this discovery. And he made this discovery almost by chance, this mystical thing, which literally covers him in gold. And then his life becomes just waiting to die.

It’s a very, very odd thing to make a movie about. But it’s a very strong movie, and there are some amazing scenes in it. The scene when Hackman first comes back to make his claim, and he meets his ex-partner by the claim office with no boots on, who blows his head off. Things like that which are very interesting and dark, they’re visionary in a movie that you’d either expect to be a mystery or political satire like Citizen Kane, or you’d expect it to be just a straight drama. But instead you keep thinking the film’s going into some other area. The whole voodoo sequence with Rutger Hauer is incredible. There are some wonderful, wonderful scenes in it. But I can imagine that when the executives looked at that they would say, “Bury it, get rid of it. Nobody wants to see this.” It’s a wonderful film, Eureka. It’s full of really unusual things.

I often feel that Bad Timing (1980) is the ultimate Nicolas Roeg film.

There are things in Bad Timing that are so daring – not daring because they’re explosive, but because they’re so raw and uncomfortable. It’s one of the great films about what we now call co-dependency. But Nic does it in the city of Freud, and in this wonderful style.

It’s a pseudo-detective story, which really works because you’re analysing their relationship rather than watching it and getting involved with it. It’s obviously what he wants you to do. There is this Art Garfunkel character, an intelligent, educated, sophisticated man – a psychologist – and his behaviour, once he’s around this woman, becomes irrational, dangerous and abusive. And you understand him completely, you understand how she’s triggered him. He’s lost. Really the only thing he can do is get as far away from her as possible, but of course he can’t. And it ends badly. I’ve never seen that stuff laid out in another movie. As a romance, there is nothing romantic about it. It’s a very brilliant film, from that point of view.

Bad Timing (1980)

The structure of it is the kind of structure which you now see in television detective shows, where it’s done to enhance the mystery. Whereas what’s beautiful about Bad Timing is that it’s never about the mystery, it’s never about whether he did or didn’t do something. That aspect of the police procedure of the film is dealt with in an almost dismissive manner. It’s just about really looking at what happens between those two people, and how toxic it is.

There is something profoundly uncomfortable about the film. You can’t imagine anyone who recognised any part of themselves in that film would even be able to sit through it. And the people who didn’t understand any of that would just reject it as being horrendous anyway. “What is this going on? Oh my God!”But the film is also very sad and very beautiful. It captures an era, the Cold War era, like a lot of Nic’s films. Because he approached the film from a plastic point of view rather than a dramatic point of view. He’s always thinking about the piece of film. There’s a lot of wonderful atmosphere and digression in his films that you don’t get in the work of more traditionally ‘well-made’ filmmakers. Just imagine Bad Timing made by Anthony Minghella. It would all be beautifully lit and performed. Everything would be in place, and there would be nothing messy in it.

So much of what is extraordinary in Roeg’s films was there from the start, in Walkabout.

Walkabout is the Rosetta Stone of Nic’s films. It has all of the themes and visual tropes that were developed in his later films. It’s wonderful how fully formed he was. One of the things that really appeals to me is how he just went out into the desert with a tiny unit, with himself as the cameraman, with his son playing the lead. They were on an adventure making that film. It was for real. I’ve never been to the Australian outback, but that film’s my image of it, indelibly. And [of] all the other films that have been made there since, not one of them seems to capture that thing that you get in that film, that vast isolation, that fact that you’re not anywhere near anything.

Walkabout (1971)

Nic is very interested in the negative outcome of sex. Sex never comes to anything good in his films. At one point he intercuts bits of a tree with David Gulpilil and Jenny Agutter. And it’s incredible, it’s almost obscene. It’s so obvious. You think, is he really saying that? But he is. This wonderful, dirty side to Nic that really works, a sexuality that’s very honest and revealing and quite disturbing. That’s what makes it never feel exploitative. There’s always a disturbing edge to it and an undercurrent of violence.

In Walkabout, especially, there’s a lot of violence against animals. The murder of Gene Hackman in Eureka is horrific, it’s much more extreme than things you see in The Godfather. There’s an acknowledgement of these things, sex and violence, that happen in Nic’s films. It’s [always] very dangerous and real and upsetting. You never feel that it’s there just to be entertaining, and that’s why the films have also a lot more impact.

He’s a director who really knows how to use music in his films.

Nic’s use of music is very surprising. It’s very eclectic and it’s changed a lot over time. Nic had a long relationship with Stanley Myers, who I knew well too. He did the soundtrack on Paperhouse with Hans Zimmer. Hans was Stanley’s assistant at the time, and he used to do a lot of the work on Roeg’s films from Insignificance (1985) onwards. Stanley did Eureka as well. Things changed a lot when Stanley and Hans got involved; the musical influences on the films tended to come from those two. Nic’s always been susceptible to outside influences.

The music is often either directly meaning something in one of his films, or he uses his score in a very romantic way. Both the John Barry score for Walkabout and the Pino Donaggio score for Don’t Look Now are great examples of classical, romantic scoring.

A lot of people say that Roeg began to lose his way in the 1980s, when the projects became more mainstream, less ambitious, perhaps.

The Witches (1989) has aged very well. It’s a phenomenally good film. Jim Henson was also a very good friend of mine. I worked for him in 1980. By the time Nic made The Witches, I knew him quite well. I met Nic around the time he was doing Insignificance and I made a music video for the Roy Orbison song he uses. Nic and I became quite good friends, and there was this film we did which I co-directed for a concert that Roger Waters gave.

The Witches (1989)

I remember thinking at the time: Jim Henson, Nic Roeg, two trains on the same track headed towards each other at high speed! Their whole energy and their whole view of life is so opposite. How is that going to work out? It was a little bumpy at times. They were facing each other with Roald Dahl in the middle.

But the film is wonderful, because Nic totally understood the darkness that’s in Roald Dahl. And Jim did too. It’s wrong to assume that Jim would be the light one and Nic the dark one. Sometimes it would be the opposite, sometimes Nic was humorous and jokey, and Jim wanted to take things more seriously. But the finished movie that came out is enduring. You can show that to kids nowadays. It’s by leaps and bounds the best Roald Dahl adaptation. I far prefer it to any of the Charlie and the Chocolate Factory adaptations.

Nic has this innocent belief in the supernatural that really powers the film. The scene where Anjelica Huston takes her face off and turns into the monster is wonderful. And obviously pre-CGI – it’s all done with editing and prosthetics. The little mice that Jim Henson did are great. They’re actually a really good compendium of very clever late 80s, early 90s special effects.

You might say, “It’s outside the mystical masterpieces that Nic made in the 70s.” But I would make great claims for that movie. I don’t know anybody who could sit through that film and not enjoy it. If you’d have said to Nic, “Why are you making this film with Jim?”, he might have said, “For the big prezzie”, but he would have been lying a little bit. The Witches is a film made by someone engaged at the full height of their powers. If you look at the numbers, I bet you it was his biggest commercial success. People talk about Nic’s career evaporating in the 80s, and then we come to The Witches, this wonderful, towering movie. So it’s a little odd.

Castaway (1986) is a film that’s aged well. It’s got a lot of really interesting things in it. It’s certainly got the last decent performance by Oliver Reed, and Amanda Donohoe was wonderful. No one had ever seen her before. It made her career.

A lot of things that Nic did during that decade were good. Track 29 (1987) is another very underrated movie. Nic has such a strong influence as a director, such a strong direct physical contact with the manufacturing of the film. When you look at Track 29, it’s less Dennis Potter than other Potter things. It’s still very much Potter’s script. There were wonderful things in it: the train sets, and Theresa and Gary. It had all these Oedipal things going on in it.

Track 29 (1988)

In this decade, when Nic’s supposed not to be firing on all cylinders, we have Insignificance, Castaway, Track 29 and The Witches. You could stack those four films against fill-in-the-blank’s name… I could name ten directors who have huge reputations who haven’t made one film as good as those four.

How important do you think was his background as a cinematographer?

Nic once repeated to me an argument he’d had with Alan Parker. Alan was being the working class hero with Nic, who sounds like an RAF officer. And Alan was going, “Ahh, you don’t know nothing, mate, I was born in Upper Street in Islington.” And Nic was saying, “Alan, you were never a workman, you went straight from art school into an advertising agency. I was a workman, I used to carry the cases up the hill.”

Obviously there was a real class divide between those two, but Nic’s point is a good one. He was a loader, a focus-puller, an operator. Then he became a director of photography, and then he became an A-list DP – he wasn’t any old DP. That’s very much a part of who he is, a camera department guy. He has a lot of those attitudes, of that background to him. He shot second-unit on Lawrence of Arabia (1962), he shot more than 50 per cent of Doctor Zhivago (1965), he shot Fahrenheit 451 (1966), Far from the Madding Crowd (1967), The Masque of the Red Death (1964). Big credits for big directors. He worked for Corman, Truffaut, Schlesinger, Lean.

Obviously the apogee of his career as a DP was doing Doctor Zhivago. Halfway through the production, he and David Lean fell out and David brought in Freddie Young, who took the Oscar for the film without acknowledging that he’d shot less than half of it. That’s an awful thing to happen to somebody. A lot of the things we remember from Zhivago were done by Nic. And actually, although I hate to say it, a lot of the things that we remember from Lawrence of Arabia too.

I don’t think Nic wanted to be a director, it was something that happened to him. He wasn’t hired to direct Performance (1970), he was hired to shoot it by Donald Cammell, but Donald didn’t know what he was doing, so Nic had to direct the film. In that sense Walkabout really is his debut, which he shot as well.

Performance (1970)

The whole thing of Nic being a DP had a lot of influence on me. When I started, I made amateur films, I was shooting Super 8 and 16mm in the 70s as an amateur, as a kid. When I first went on a movie set, which was for The Dark Crystal (1982)… Dark Crystal was a little odd because Jim Henson was directing it, and he wasn’t operating a camera. He was underneath the set operating puppets, and you couldn’t tell what was going on.

It may have been the first time I was hired professionally, but whenever it was, I realised that I was about to direct something, and I went to pick up the camera, and somebody said, “What are you doing?” This was the very unionised early 80s British film industry. “You can’t do that, that’s the camera operator’s job.” I remember thinking, “Well, what am I going to do with it?” I didn’t understand that the director wasn’t the guy holding the camera.

We’ve come full circle now. In future it’s going to be the guy holding the camera because the camera’s going to be so small you’re just going to hold it. If you are the person looking through the lens at the actor, you have a different relation to them than if you’re sitting back and looking at them on a television monitor because you’re actively involved in the shot.

A lot of people have said to me – because I shoot and operate while I direct – “How can you tell what the performances are like?” If I’m just sitting there, it’s as if I’m just watching TV, but if I’m holding the camera, and leaning into them, I’m helping them, I’m with them, right there. You can screw up, and you do screw up if you’re operating, so it’s a level playing field. I understand that you can’t do it unless you’ve trained to do it and got a lot of knowledge and you certainly can’t do it on a big set unless you know what you’re doing, because people stop you very quickly. But it’s what Nic did and still does.

Nicolas Roeg directing on the set of Bad Timing (1980)

Obviously he hired people who were his assistants, who took the credits on the later films, like Tony Richmond. I hired Tony to shoot Candyman, and the only reason I hired him was because of his relationship to Nic.

There is a kind of grandfathering that happens in the camera department – at least that’s how it was in the old days. Camera teams used to stay together for entire careers – operators, focus pullers, loaders, and then they would move up. They would get promoted, but it would take time. So Nic promoted Tony, and then whoever was Tony’s assistant would become… It would go on like that. So you could get the information from whoever they’d been working under, and it would be a filtering down from all those cameramen to you.

I wanted Tony, because I wanted to know everything that Nic knew, as a DP, and it was a good way of finding out. I found out that Nic only uses direct light, I found out how he would do that thing where he would shadow it in on the eyes, which he did in Dr Zhivago a lot, because Tony did that in Candyman. I didn’t even ask him to, but I knew that he would, and I knew where he had been taught to do it from.

What’s striking today is how free Roeg is in using the zoom lens.

The zoom is a very interesting subject; it became an issue around about 1991. There must have been a meeting of DPs somewhere, they all got together and said to each other, “The zoom thing, we’ve got to stop it. And we’ve got to punish anyone who brings one out again.”

No one ever told Stanley Kubrick: in Eyes Wide Shut they’re still zooming. Ask Visconti, ask Kubrick, ask Nic Roeg, the zoom is a great tool. It means something different from tracking. It became a thing that DPs would say, “You should track, not zoom.” But tracking gives you a different sensation, because it changes the perspective. A zoom flattens as it goes in, and flattens as it comes out. The zooms in Barry Lyndon wouldn’t work as tracks; nor would the zooms in Nic’s films. They’re for emphasis. If you look at Altman, all these people, they were all masters of the zoom.

It’s true that the zooms made in the 1930s had optical problems – they would do what was called tromboning – they would distort when they got to the other end. If you pulled focus on them it would look like they’d shifted perspective. They were optically dodgy around the edges. There were a million technical reasons why 1970s zooms sucked, but if you’ve got one now they’re worth a fortune because they have a look. There was an over-reliance on zooms. It was a television thing – every shot went zoom – but the ways the zoom lens was used by Nic, Kubrick and Visconti is a powerful tool. We should now be over this 90s DP fetish where it was better to do a really boring tracking shot instead of a zoom.

Insignificance (1985)

The first thing I did professionally with Nic was make this music video for Roy Orbison’s Wild Hearts Run Out of Time for Insignificance. I went to Nashville to shoot some stuff with Orbison. Then it was going to be cut into footage from Insignificance, which is what we did. I had to match the camera style Peter Hannan had used in Insignificance, which was very interesting: I was tracking on something and then suddenly zooming in on somebody’s drink. The cameraman at the time turned to me and said, “What are you doing?” The moment he said that, I thought, “I’ve got Nic’s style.” Not that I make any great claims for that video, but you can see that it was quite intricate to make the camera style run from one element to the other without seeming to jar.

With Nic, his camera probes and looks for things. He uses handheld very brilliantly. If you look at Don’t Look Now, 60 per cent of that film is handheld. And most people are just unaware of it when they watch the film. It’s done in a really loose, nouvelle vague style. A lot of The Man Who Fell to Earth is done in handheld as well. To me, handheld done properly is a uniquely human perspective, because it’s how we perceive the world. And it’s that sense of things being there, and coming towards you and going away.

Nic uses the zoom lens to emphasise objects that you might not necessarily see in a frame. They’re often eccentric and he’ll pick up on a prop or a detail. In Bad Timing, Art Garfunkel’s suddenly twisting his hair. Nic just pushes in on things. It’s not even for emphasis so much as what he’s noticed. That’s what gives the film its poetic status, and a realism too. That’s not there when you have a very kind of determined, traditional camera that basically just shows everything in focus, and just moves between the people who are talking.

I find all these techniques help Roeg to blur the barriers between objectivity and subjectivity, reality and dream.

The great directors understand that a film is a representation of two kinds of dream states – a waking dream state, and a sleeping dream state. One of the things that we most ignore is that often, when we are supposedly conscious, we are actually in a dream state because we’re not concentrating on the thing at hand. We’re thinking about the woman we met last week, whether we are hungry or something terrible.

Nic creates those feelings, and he knows how to do that in a very unforced and subtle way. His films are poetic rather than literal, in the same way that Pasolini’s are. When you look at something by Pasolini, and everything’s mythic, it’s often almost like a documentary about the ancient world. You’re thinking, “How did he do that?” You think he went back in time to shoot them. And that’s why they’re so devastatingly good.

Don’t Look Now (1973)

When you look at Nic’s films, they’re very present and contemporary and perceptive about the world that’s going on around him. In a film like Don’t Look Now, the Venice he shows you is pretty much what you would have already experienced. He wouldn’t show you touristic shots of St Mark’s Square.

When you go to the Vienna of Bad Timing, he’s got the scenes on the tram, people just hanging there. That’s what Vienna’s really like. There’s a really intricate realism to his fantasy. Even just someone hanging onto the strap in a tram in Vienna, it’s all about their state of mind, it’s about Garfunkel being paranoid that his girlfriend’s screwing someone else. That’s the brilliance of what Nic does with the music, the performances and the photography. If you just analyse them as disparate elements, it’s a shot of Art Garfunkel on the tram, but it’s not, it’s completely expressionistic, you completely understand his state of mind on the tram without it being verbalised. It’s actually much more of an achievement than you realise.

What are your thoughts on Roeg’s directorial career as a whole?

Nic is one of those people about whom I can honestly say I’d have been proud to have made any one of those films. A lot of them are among my very favourite films of all time.

So you say, “Why is he not more publicly acclaimed?” Well, he is by the people who know him. And if you do see his films, it’s impossible not to be really affected by them. Nic was never very interested in success, never very ambitious. He had opportunities – most notably when he was supposed to be making Flash Gordon for Dino De Laurentiis. That was meant to be Nic’s mainstream moment: big opportunity, big budget. But there was no way Nic was going to make the film that De Laurentiis wanted. Both men had the honesty to understand that and part company.

It was the same situation years later with David Lynch and Dune. We can all make excuses for Dune – but it’s a train wreck. Sometimes things aren’t meant to happen. It’s a mystery to me why some films are praised, but there are other forces at work, and a lot of them are to do with the amount of money spent on promotion. They have to promote something, and they have these prizes and they have to get up a certain amount of steam for it. There’s a system there that has to be engaged, and if you don’t engage in that system in the right way, it’s not going to happen for you.

The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

I don’t know if it was Godard who said this, but it’s more true today than ever. If you cut the credit titles off all the films that were Oscar-nominated last year, even the year before, and switched all the names around – the directors’ names – it would all be the same. Because the way that those people make decisions is very codified and standard. There’s a certain kind of performance that’s acceptable, and a certain kind of editing. But it won’t last.

It’s like if you go into a museum, and you see the genre of painting, from the late 19th century, that was so heavily praised at the time, depicting Greek gods and nymphs. And you look at these paintings and it’s just one shit painting after another. And those are the ones they’ve left in the galleries – most of those paintings are in the basements of the museums, under covers. Those are the artists who were praised to the sky and honoured and given everything. And they’re paintings that aren’t… they’re horrible.

You look at the paintings of the Impressionists and the people that came after them. They still really speak to us in a way those other paintings don’t. And of course at the time those paintings were ridiculed and disliked, especially in the case of people like Van Gogh. But what we respond to now about them is their humanity, their directness and their honesty. What people responded to at the time was just how well it fitted into the mode and the convention. This is a pretty bog-standard story with art.

Nic’s work will last. A hundred years from now we’ll be looking at Nic’s films. We’re not going to be looking at the films of blah blah, who won the Oscar last year. It doesn’t matter who they are, because they’re all the same, those people. They’re just people who were promoted by Harvey Weinstein one week.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.