Though his last feature – Puffball – was made in 2007, Nicolas Roeg was still up until his death defiantly regarded by many as Britain’s finest living director. His most celebrated film, Don’t Look Now (1972), won a Time Out poll in 2011 as ‘Best British Film’. And in the same poll, his debut – as co-director with Donald Cammell – Performance (1970) came seventh.

Not that Roeg’s films ever seemed calculated to score highly at the box office or ingratiate themselves with audiences. His achievement was more in the nature of provocation and exploration, looking into the darkest recesses of human behaviour and never taking any easy route through narrative cinema. His particular obsession with playing with time, and editing through association of imagery rather than classic mise-en-scène, gave rise to the much-used critical term ‘Roegian’. His films got under your skin, made you feel emotions you might prefer to block out, carried you into a dream state where you saw the world in a different and challenging way.

In Don’t Look Now, Roeg took Daphne du Maurier’s novella about a married couple whose recently dead daughter seems to reappear to them in Venice and created a disturbing visual mosaic that played with the surfaces of glass and water as well as the colour red. According to screenwriter Allan Scott, who wrote several of Roeg’s films, during production the rushes were viewed in black and white, so that the fleeting glimpses of a figure in a red raincoat scuttling around the dark, narrow streets of Venice only became apparent when it was completed.

Don’t Look Now (1973)

Changing the death of the child from meningitis to an accidental drowning provided an extraordinary opening sequence, in which a damaged photographic slide bleeding red gives the father (Donald Sutherland) a premonition of what is about to happen to his daughter. It was a typical Roeg sequence in that all the elements were juggled through some brilliantly timed edits, pushing the viewer into a state of perpetual wonder and terror.

Of course the film became notorious for another Roegian trope, an unusually (even for its day) explicit sex scene between Sutherland and Julie Christie that was absurdly taken for the real thing because of its rare quality of intimacy. Roeg made screen sex appear both extraordinary and everyday by slyly intercutting the couple naked in bed with them dressing to go out. It was the very shamelessness of Roeg’s approach to the erotic that marked him out, for as Danny Boyle pointed out, no-one else in British cinema could match him in this realm. Many of Roeg’s films dealt with couples whose lives were torn apart by their fluctuating desires, most overtly in Bad Timing (1980) and Castaway (1986).

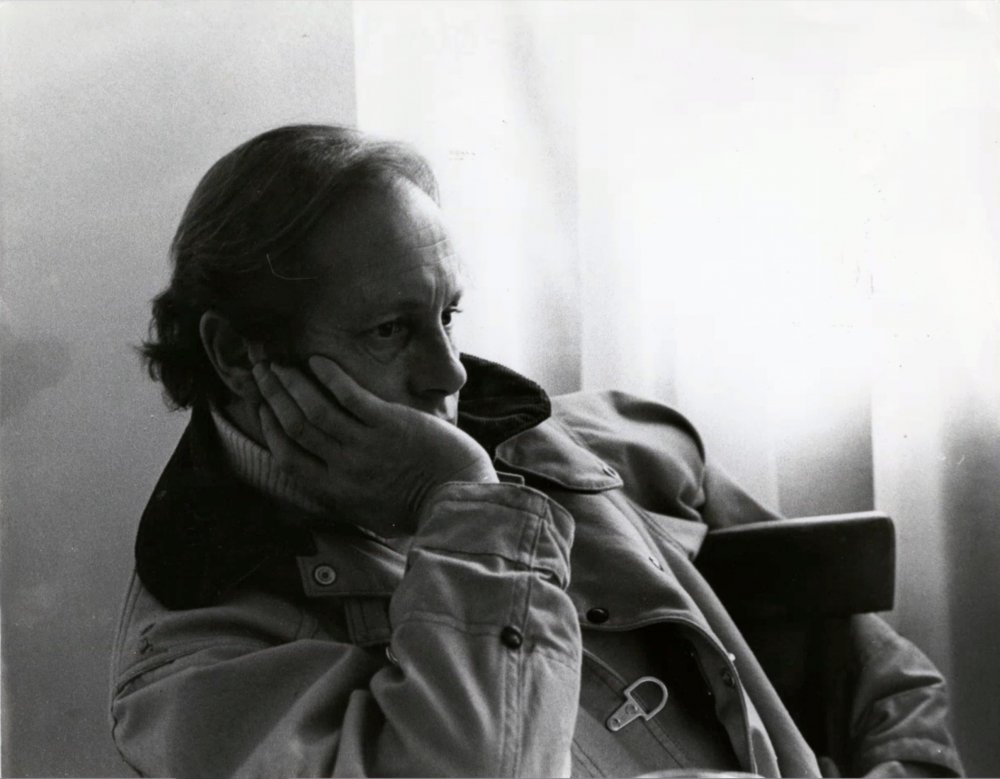

All this might have seemed surprising to anyone who met Nicolas Roeg, for as Bernard Rose observed, his demeanour suggested an old school RAF officer rather than a tortured artist. Actually, when Roeg grew up during World War II in Southern England, he used to watch the aerial dogfights and dreamed of being up there in a Spitfire himself.

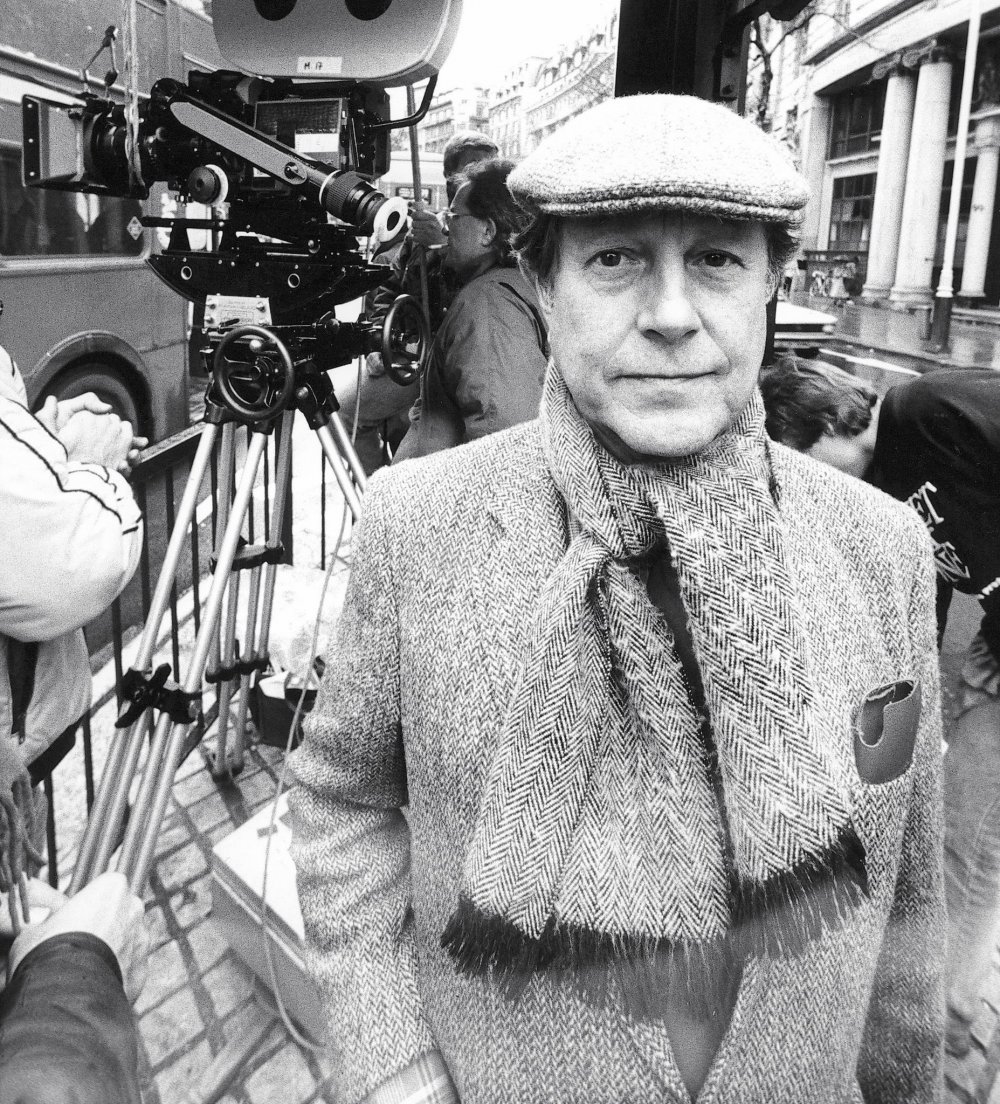

Nicolas Roeg directing Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie on the set of Don’t Look Now (1973)

In the event, by the time he might have qualified for the job the war was over, and he drifted into the film business at the lowest ranks, carting film cans up and down Wardour Street and making tea in the cutting rooms. But it was during lunch hours when he was let loose on an editola that he discovered the magical properties of film, and how by running it back and forth he could play with time.

When an opportunity came up to join the cinematographic department at Borehamwood studios, he began working on sets as an assistant, clapper boy, loader, focus puller and eventually operator. In the 1960s he became a director of photography or cinematographer, which meant he designed the composition and lighting of shots and commanded his own unit. On one of his early credits, A Prize of Arms (1962), he also acted as co-writer (a scene in which the main character senses his planned robbery will be jinxed by rainfall possibly points to his later preoccupation with psychic phenomena). Roeg’s craft was outstanding in the film version of Pinter’s The Caretaker (1963), Roger Corman’s flamboyant Edgar Allen Poe adaptation The Masque of the Red Death (1964) and John Schlesinger’s Hardy adaptation Far from the Madding Crowd (1967).

Far from the Madding Crowd (1967)

A key collaboration was with Francois Truffaut on his only film in English, Fahrenheit 451 (1966), notable for its ‘toytown’ primary colours with gleaming red fire engines despatched to burn books. He also added a strong visual flair to the two films he shot for Richard Lester, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966) and Petulia (1968), Intriguingly, the kaleidoscopic nature of the latter film with its fractured editing and hippy attitude seemed to suggest things to come.

What should have been Roeg’s crowning moment as a cinematographer, on David Lean’s Doctor Zhivago (1965), ended abruptly with him being dismissed and replaced by Freddie Young. Roeg had previously served on the second unit of Lawrence of Arabia (1962), but Lean apparently became suspicious of Roeg’s adventurous nature and technical bravura, and resented how he impressed producers with effective solutions to problematic scenes. While Roeg’s work is still visible in sections of Doctor Zhivago, that year’s Academy Award for cinematography went solely to Young.

Performance (1970)

But by the late 60s, Roeg’s focus was more on becoming a director, and an opportunity presented itself to act as both cinematographer and co-director alongside writer Donald Cammell on Performance (1970). Cammell, a dandyish, successful society portrait painter, had written a screenplay which brought the society of East End criminals together with the decadence of the rock world, with a smart young gangster (James Fox) hiding out from his boss in the Notting Hill basement of a reclusive musician (Mick Jagger). The shooting of the film became a legend in itself, with reported drug-taking and sexual shenanigans on set. But the partnership of Roeg and Cammell was mostly harmonious, with the former pushing the envelope with optical distortions and different film stocks.

Unfortunately Warner Brothers loathed the first cut of the film, even threatening to sue Roeg for professional incompetence. Cammell fled to Los Angeles and eventually produced a version that was released two years after the shoot. Subsequently Performance became the cult film sans pareil, and is still one of the most compelling portraits of the London criminal world ever put on screen. In recent years it has emerged that much of Performance’s jagged editing and hallucinatory atmosphere was really down to Cammell, but the film stands as a brilliant reflection of its time and a highly successful collaboration.

Walkabout (1970)

Roeg’s real first feature was Walkabout (1970), a richly imagined and visually arresting account of two white siblings marooned in the Australian outback and joined by a wandering aboriginal youth with whom they share no verbal language. The casting of a teenage Jenny Agutter and Roeg’s son Luc (now a film producer) alongside David Gulpilil proved perfect, and the film was shot almost documentary-fashion by a tight crew in tough locations. As often in the case of first features, most of the director’s trademark elements are present in Walkabout and delivered with a fresh intensity – the uncoy eroticism, the surprising editing, the freely zooming camerawork, the eclectic choices of music, and the enquiring eye on a world both familiar and strange.

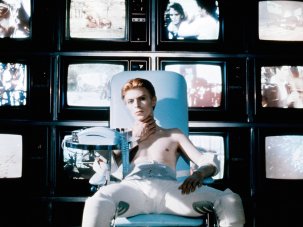

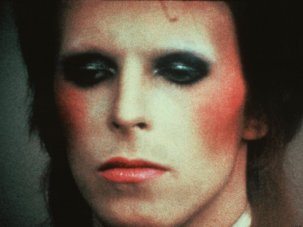

The 1970s proved to be Roeg’s finest decade. Don’t Look Now was a considerable success, and was followed by the more ambitious sci-fi saga The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976). David Bowie was inspired casting as the pale-skinned alien taking on human form whose mission to save his own planet is derailed by a decline into alcoholism and the corporate powers who resent his technological genius.

The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

It featured several of Roeg’s most audacious experiments in time travel, which came even more to the fore in Bad Timing (1980), a psycho-sexual drama examining why the relationship between an American psychologist (Art Garfunkel) and a younger free spirit (Theresa Russell) ended in an attempted suicide and rape. Brilliantly shot by Tony Richmond and boldly edited by Tony Lawson, the film swings between different stages of the affair yet never loses an inner coherence. Bad Timing was not likely to please an audience weaned on romcoms (one studio executive famously commented that it was “a sick film made by sick people for sick people”), but its complex interweaving of themes of romantic obsession and voyeurism place it up there with Hitchcock’s Vertigo in the pantheon of perverse masterpieces.

Bad Timing (1980)

By this stage Roeg was gathering a regular circle of collaborators, and both producer Jeremy Thomas and writer Paul Mayersberg, as well as his second wife and muse Theresa Russell, came together to make his most ambitious film, Eureka (1982). A powerful fable of a man (Gene Hackman) whose discovery of gold brings about both his success and his downfall, its unashamed fluctuations in tone and pace (it begins with an orgasmic strike and ends in a romantic courtroom scene) was both its richness and its difficulty; it was poorly distributed and divided critics, even those who had previously supported him.

Eureka (1982)

After Eureka, Roeg had to take on slenderer projects that while always engagingly cinematic, never quite regained the intensity of his previous work. Insignificance (1985) was a cleverly realised transposition of Terry Johnson’s play about an imaginary encounter between Albert Einstein and Marilyn Monroe. Castaway (1986) was the true story of an unlikely couple tearing each other apart on a desert island. Track 29 (1987) saw Roeg linking up with Dennis Potter in a teasing tale of reality and fantasy. But commercial success only came again with Roeg accepting to make a children’s film, an adaptation of Roald Dahl’s The Witches (1989), in which pre-CGI in-camera trickery reflected the director’s own joy in playing with reality on its own terms.

The Witches (1989)

The difficulties Roeg had setting up projects in the 90s were linked to major changes in an industry that favoured heavily publicised blockbusters over speculative medium-budget productions, especially those from a director who was liable to take a film to places most executives fear. His one early chance for the big-time, making Flash Gordon for Dino De Laurentiis, found him at odds with the producer over how wickedly adult an approach he could take to the material. Cold Heaven (1992), Heart of Darkness (1993), Two Deaths (1994) and Full Body Massage (1995) were all seen on television screens, where experimentation was even less encouraged.

Like many directors, he filled in time making commercials (including those tea-drinking chimps), some pop videos and that infamous public warning film about AIDS featuring a menacing tombstone. After a long absence from the cinema Roeg returned with Puffball, an adaptation of Fay Weldon’s novel about witches and fertility, but its engagingly perverse streak was sadly unsupported by its production values.

Puffball (2007)

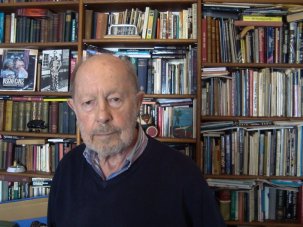

While Roeg never gave up hope of making more films, supported by his extended family of six sons and third wife Harriet Harper, he produced a book about his life and career, The World Is Ever Changing. Of course, being in his own words, it was neither chronological nor detailed, more allusive and quizzical, quoting as many poems as scenes from films.

A conversation with Roeg was almost as challenging as watching his films, as he confessed himself to possessing a grasshopper mind and he would rarely answer a question in any straightforward manner. But often you were rewarded with shafts of lucidity, such as when he once explained to me in great detail his ideas for a film on the hapless yachtsman Donald Crowhurst, which he saw as a ghost story. I was fortunate, thanks to the intercession of our mutual friend the photographer Michael Woods, to have the opportunity to persuade Roeg into participating in a documentary on him for BBC’s Arena. An often capricious fellow, he had turned down several approaches before and until the cameras actually turned, I was never really sure it would happen.

Nicolas Roeg was in many ways a unique figure in cinema, and he inspired a high degree of reverence from fellow filmmakers, even if they didn’t envy his struggles over many years to get back on the set. Perhaps in some ways he is was, as Bernard Rose suggested to me, the real man who fell to earth, not just because of his awesome fondness for gin martinis but for his perceptions and brilliance in creating a cinema that posed a threat to the mainstream. On set he was notorious for shooting a great deal, responding to accidents and changes in weather as if they were always intended for the film in question. He loved chance while never really believing in coincidence.

This summer, I attended the New Horizons Festival in Wroclaw where a Roeg retrospective was held. Every screening was full with a predominantly young audience most of whom had never seen his films before, and they were enraptured by them. He truly was one of British cinema’s great visionaries, up there with Powell and Pressburger and David Lean, and I believe his films continue to improve with time, as one viewing is insufficient to discover their many secrets.

Nicolas Roeg

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.