Crime and noir: the 1940s

The 1940s were a boom period for Mexican cinema thanks in large part to increased investment from the United States and the development of the Banco Cinematografico, a fund aimed at modernising production means. It was a decade that bore witness to the growth of the fledgling Mexican auteur cinema – directors like Fernández, Roberto Gavaldón, Julio Bracho and Alejandro Galindo dominated – as well as the consolidation of the Mexican star system, in the prevailing image of María Félix, Dolores del Río, Pedro Armendáriz or Arturo de Córdova.

While much of the world was reeling from the effects of World War II, Mexico benefited from a long period of uninterrupted economic growth – often referred to as the Mexican Miracle – that lasted from the 1940s well into the 60s. Rapid industrialisation, modernisation and urban development saw the emergence of a new, wealthy middle-class that flourished under the governments of Manuel Avila Camacho (1940- 46) and Miguel Alemán Valdés (1946-52). But with urban growth came a series of new social problems, including the development of barrios bajos (poor, slum-like neighbourhoods) that were home to a criminal underworld peppered with cabarets and bars, where money talked and morality was increasingly redundant. With their undertones of melodrama and detective cinema, films like Bracho’s Another Dawn (Distinto amanecer, 1943) and Twilight (Crepúsculo, 1945); Gavaldón’s The Other One (La otra, 1946), The Kneeling Goddess (La diosa arrodillada, 1947), In the Palm of Your Hand (En la palma de tu mano, 1951) and The Night Falls (La noche avanza, 1952), or Galindo’s Los dineros del diablo (1953) began to reflect a preoccupation with the fate of the new urban man.

Bracho’s films are key to understanding the emergence of the film noir genre in Mexico. Another Dawn is essentially a crime thriller, telling the story of Octavio (Armendáriz), a union member looking for documents that will implicate a corrupt governor, and Julieta (Andrea Palma), an old flame from his university days. What sets the film apart is its positioning of the shadowy city as protagonist, with its violence, criminality and clandestine spaces (most notably the cabaret), as well as DP Gabriel Figueroa’s moody photography and the presence of a mysterious, seductive female character, who, if not quite a femme fatale, is certainly a predecessor.

Twilight is a much more fatalistic take, charting the terrible moral undoing of Alejandro (De Córdova), a surgeon tortured by obsessive desire for his best friend’s wife Lucía (Gloria Marín). An intense and dark psychological thriller, the film was unusual both for its time and within Bracho’s own body of work, closer thematically to Buñuel’s El (1953, also starring De Córdova as a man destroyed by female sexuality). Alejandro’s descent into psychosis begins the moment he lays eyes on a naked stone statue of Lucía in one of the film’s most striking sequences – “That’s when I first saw the shadow of the monster that would lead me to tragedy,” he muses, as the shot fades to black and we cut to Lucía’s brightly lit, immobile face. Though Lucía still isn’t quite a femme fatale, and while the film displaces her threat on to the stone statue (an important symbol that would be developed in Gavaldón’s noir film The Kneeling Goddess), her presence is devastating to masculinity and order.

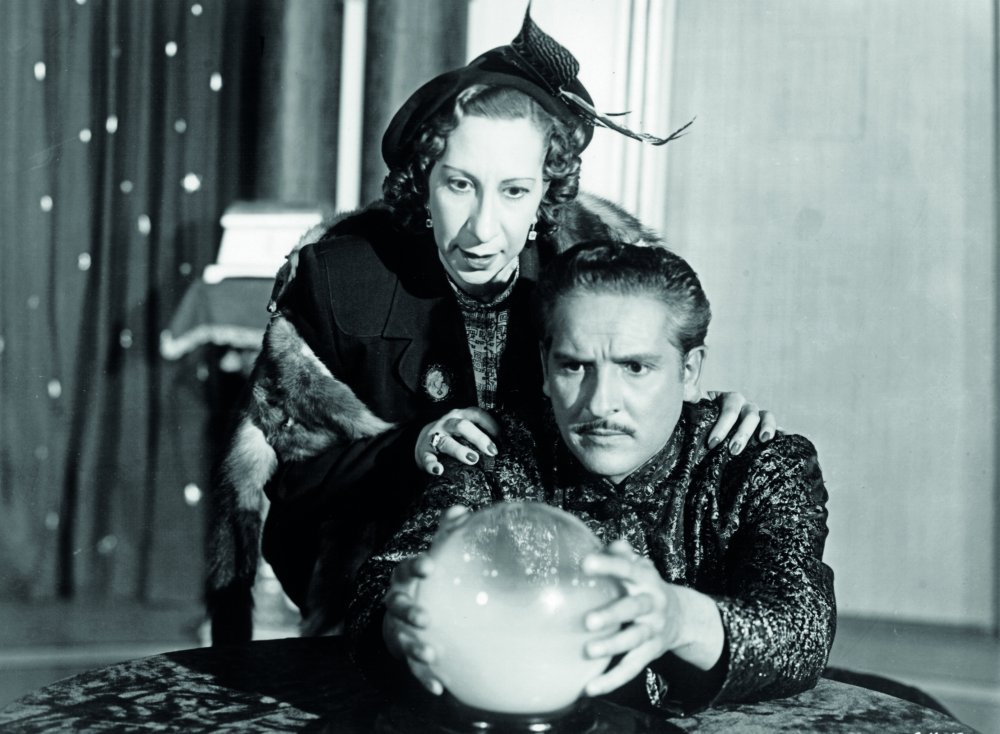

Twilight was followed by a series of important collaborations between Gavaldón and Alex Phillips. In The Other One, one of the first great films about social disenchantment in Mexico, foreshadowing Buñuel’s Los olvidados (1950), María (del Río) is a poor manicurist who, obsessively jealous of the affluent lifestyle of her sister Magdalena (also played by del Río), contrives a plot to assume her identity. Driven by a cold ambition and lack of moral conscience absent in representations of women in the revolutionary or melodramatic models, María is much closer to the kind of femme fatale typical of the then burgeoning noir scene in Hollywood, or even in Gavaldón’s own In the Palm of Your Hand, in which De Córdova plays an unscrupulous clairvoyant devastated by the influence of the cruel and unfeeling Ada (Leticia Palma). María is, at once, both femme fatale and protagonist, seducer and seduced, self and other, a duality that Gavaldón and Phillips explore by way of oblique camera angles and the repeated motif of the mirror, which suggests not only a fear of the double nature of women (María/Magdalena) but also of a perceived moral decline towards unscrupulous greed.

While it is only with hindsight that these films have been grouped together as examples of film noir – they have also been called political or crime thrillers, police films, even urban melodramas – their fascination with clandestine city spaces, criminality, neurosis, duplicity, the undoing of the modern man and the terrifying sexuality of his female counterpart, is deeply connected to the urban panic engendered by rapid modernisation in Mexico in the 1940s. And if they ostensibly offer a kind of counterpart to the rural films made during the same period, or to certain aspects of the melodrama, they also reflect the same fear of rapid development; that same yearning for values lost, or desire to understand what it meant to be a modern Mexican.

Enamorada (1946)

An alternative Mexico: Emilio Fernández and Gabriel Figueroa

At the same time that noirs were enjoying popularity at the Mexican box office, one of the Golden Age’s most important and prolific directors, Emilio Fernández, was also gaining notoriety (both at home and abroad) for a wholly different kind of cinema. In her 2012 book on Fernández, Dolores Tierney highlights the period between 1943 and 1950 as one in which he “was regarded as one of the foremost purveyors of ‘Mexicanness’”. A string of films made during that time – including Wild Flower (Flor silvestre, 1943), María Candelaria (1944), Enamorada (1946), The Pearl (La perla, 1946), Río Escondido (1947) and Maclovia (1948) – offered a new style of Mexican cinema, one that celebrated a rural and conservative (often indigenous) Mexican identity.

Mexican writer Julia Tuñón Pablos has suggested that the director’s filmography is “characterised by its single-mindedness… [we] can look at it as if it were a single film” and, certainly, these films present a homogeneous and easily recognisable cinematic universe, replete with the same visual motifs: vast dramatic skies that overwhelm the human figure; trees, magueys and cacti; monuments (churches, temples, statues) that represent tradition and order; long, low-angled shots that highlight landscapes or extreme close-ups of Mexican faces. Narratives tend to be driven by the same prevailing ideology – what Fernández himself called a ‘thesis’, necessarily containing a strong moral and social content – and focused on nationalism, the plight of the indigenous people, or the need for education. What’s more, through most of the 1940s the director worked not only with the same DP (Figueroa) but also with the same writer (Mauricio Magdaleno), editor (Gloria Schoemann) and, more often than not, the same cast (Pedro Armendáriz, Dolores del Río and María Félix).

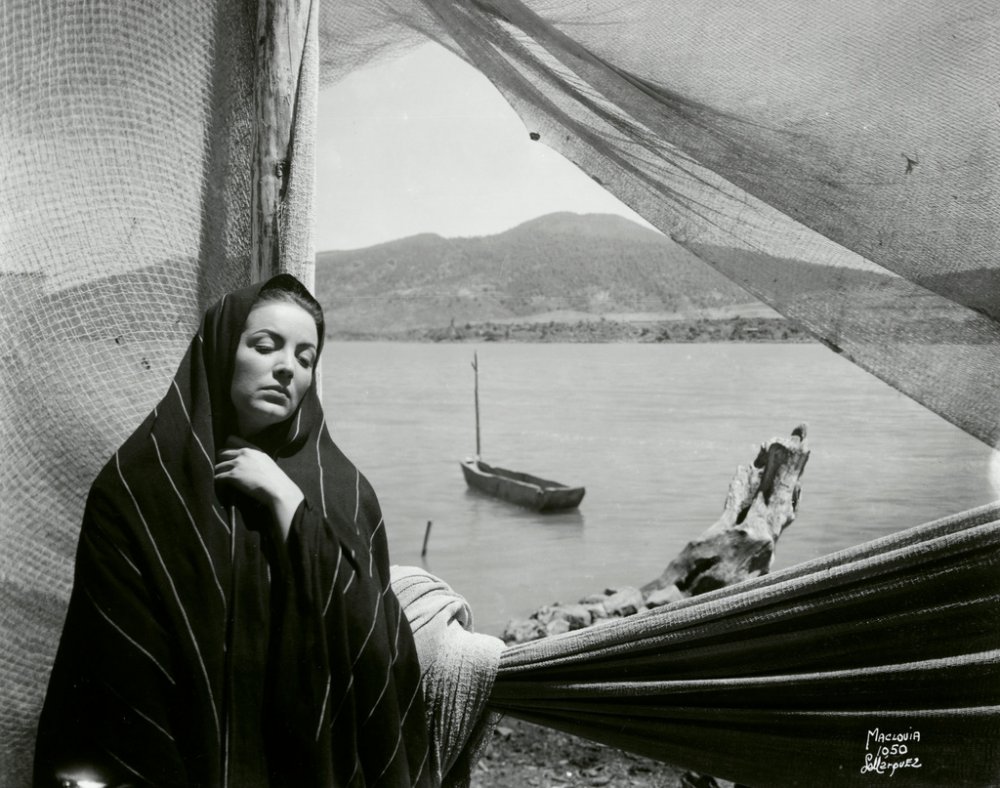

In Maclovia, perhaps one of Fernández’s most representative rural films, Armendáriz and Félix play poor, illiterate lovers from the indigenous island of Janitzio. A simple and harmonious order is reflected by Fernández in the way he privileges image over dialogue – in a series of long, slow-moving shots of the fishermen at work (reminiscent of Emilio Gómez Muriel and Fred Zinnemann’s 1936 socialist film Redes), or the framing of Maclovia against dramatic Michoacán skies, always wrapped in her trademark shawl. But the island’s harmony is disrupted by the arrival of soldiers from the mainland; soldiers with “ojos claros” (light-coloured eyes) who have no respect for indigenous order (the laws of the island state that no one can leave, and that Janitzio’s women should only marry its men) and who look down on the “indio mugroso” (dirty Indian).

In Enamorada, a romantic comic melodrama also starring Armendáriz and Félix as lovers, a proud revolutionary general, Juan José, falls in love with Beatriz, the rude and haughty daughter of one of the town’s richest men. Félix here plays the archetype of the role she was already becoming known for – strong-minded and beautiful, a subjugator of men – while Armendáriz, though brutish and macho, is ultimately presented as an anti-capitalist defender of the poor (at one point he berates a local merchant: “You monopolise the stock and raise the prices. And what about the people? Let them pay! And let them starve!”). Resolution is achieved when Beatriz is finally won over by the general’s charms and takes on a subservient role, rejecting wealth and family in favour of purer revolutionary ideals.

Just as Maclovia is concerned with upholding the dignity of the poor, indigenous Mexican against a threat from external forces, Enamorada essentially posits the Revolution as a noble cause, necessary to protect the integrity of the Mexican pueblo from capitalism and greed.

Like other films made by Fernández and his team in the 40s, both Maclovia and Enamorada aimed to develop an almost mythical style that would consolidate the Mexican identity around traditional values and thereby, like the melodrama, go some way towards soothing post-revolutionary fears. That these films were so successful abroad (Fernández’s films screened at Venice, Locarno and Cannes, where he won the Grand Prix for María Candelaria in 1944) also suggests that this was a vision of Mexico that was universally popular, easy for non-Mexicans to assimilate and seeming to substantiate the director’s claim that “there only exists one Mexico… the one I invented”.

Victims of Sin (1951)

Rumberas: late 1940s and 1950s

Though reportedly with some reluctance, Fernández also began making urban films at the end of the 1940s, perhaps because by then his formulaic model was beginning to fall out of favour with Mexican audiences. Films like Salón México (1949) and Victims of Sin (Víctimas del pecado, 1951) represent a transition from the director’s rural, more nationalistic work towards more urban concerns, specifically the increasingly popular rumbera film. A fascinating hybrid genre, the Mexican rumbera had manifold and disparate influences, including the extravagant studio musicals made in Hollywood in the 1930s, the femmes fatales of film noir (both Mexican and from abroad) and the Afro-beats of Cuban rumba music, wildly popular in Latin America for most of the first half of the 20th century. Much like Mexican noir, the genre reached its peak during the late 1940s thanks to a boom in city nightlife and cabaret culture.

In Salón México, Mercedes (Marga López) is a cabaret dancer and prostitute who works with the sole purpose of supporting her virtuous younger sister Beatriz and providing her with an education. In Victims of Sin, Violetta (Ninón Sevilla), also a dancer and prostitute, adopts the baby son of a co-worker after she unceremoniously throws him in the bin (significantly, a bin located directly in front of Mexico City’s Monument to the Revolution) shortly after giving birth. Both films stick closely to the values established by Fernández’s earlier work: consider a scene in Salón México in which an impassioned speech on heroism (essentially defined as self-sacrifice for the nation) is interrupted by a cutaway to military planes flying overhead; or a cabaret owner in Victims of Sin telling Violetta that in his brothel there is no hierarchy: “We are all common, working people.” What’s more, even while both protagonists are prostitutes, and even if they are presented as independent and strong-minded, Fernández’s films made sure to position both women in the role of self-sacrificing mother, representative of and reproducing traditional values and structures. Salón México’s musical refrain, which references the country’s first indigenous president, leaves the director’s position clear: at the end of the film, from the dark street outside the cabaret we hear: “[Benito] Juárez shouldn’t have died. The nation would have been saved. Mexico would be happy”.

Salon Mexico (1949)

Alberto Gout’s Aventurera (1950), commissioned as a star vehicle for Sevilla, is widely considered the masterwork of the rumbera genre and offers a much more telling example of the shift in representation of women during this period of Mexican cinema. Sevilla plays Elena, an upper-middle-class woman sold into prostitution by a criminal acquaintance after her mother has an affair and her father commits suicide. Rather than positioning the virtuous mother against the figure of the fallen woman, the film quickly disposes of the maternal to engage instead in an unabashed and fetishistic celebration of Elena’s beauty, street-smarts and barely contained eroticism. A fast-paced plot, peppered with extravagantly choreographed dance numbers (arranged by Sevilla herself), does something to distract from the extraordinary cruelty that Elena suffers in the film’s first half. Critical of the city space as criminal and violent (the film takes place in the cities of Ciudad Juárez, Mexico City and Guadalajara), Aventurera is unusually liberal in allowing its protagonist the possibility of a happy ending, perhaps paving the way for films that would deal more kindly with prostitution in years to come, or even heralding the fichera films or sex comedies (Mexican cinema’s answer to Carry On…) of the 1970s and 80s.

Macario (1960)

Macario and Mexicanness: 1960

Towards the end of the Golden Age, Gavaldón made Macario (1960), a magic-realist fantasy set in colonial Mexico about a poor peasant who makes a pact with Death. Featuring extraordinary photography by Figueroa, the film is ostensibly a folk tale that weaves a fascination with death (both Gavaldón’s and Mexico’s) into a narrative about a poor campesino desperate for something beyond the daily grind of back-breaking work and near-starvation. Aside from being Mexico’s most successful cinematic export ever, breaking even Fernández’s record by gaining a nomination for Best Foreign Language Film at the Oscars and screening in competition at Cannes, the film was also a hit at the Mexican box office. Although it was based on a novel, which was itself inspired by a Brothers’ Grimm story, the film’s mythical vision of Mexico was so successful that, according to the critic and filmmaker Ariel Zúñiga, “an anthropologist researching the legends of southern Mexico discovered that the plot of the film had been totally assimilated into the mythology of the region”.

Macario’s fictional representation of Mexico and Mexicanness was so popular, then, that it was even assimilated into the country’s own oral history, an anecdote that offers a neat example of just how symbiotic the relationship between cinema and cultural identity in Mexico could be. Not only did films made through the Golden Age emerge in response to, or as a reaction against, a constantly shifting set of socio-political and historical circumstances, but the people also looked to these films as examples of how to navigate a complex and confusing new reality, seeking out structures and archetypes that might help them to reidentify themselves as Mexican.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.