Web exclusive

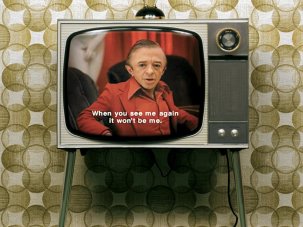

The Fall (2013)

For years audiences in the UK have been turning to foreign imports like Breaking Bad from America, The Bridge from Denmark or The Returned from France in order to find artistically challenging TV drama that is unafraid to confront the darker side of life.

Season 2 of The Fall is currently broadcasting on BBC2. Southcliffe is available on Channel 4 OD and will be broadcast internationally on Netflix.

Of course, there is a great irony to this as the UK was once known around the world as the home of high-quality TV drama. The works of Alan Bleasdale, Dennis Potter and Peter Flannery, to name a few, are acknowledged as some of the best in the format’s history. The creators of Scandinavia’s golden age of TV drama cite DCI Tennison, the female protagonist of Prime Suspect, as the influence behind heroines such as Sarah Lund of The Killing and Saga Noren of The Bridge, and US remakes and subsequent international syndication have made UK productions such as Brideshead Revisited and House of Cards international household names. So what went so horribly wrong?

“We’ve been through a period in the last ten to 15 years where it’s been difficult to get excited about a lot of it,” says Gub Neal, producer of the critically acclaimed The Fall, season 2 of which is currently broadcasting on BBC2. British television’s recent culture, he says, has been to “commission the stuff you can get back again and again, and in very high volume.” This was an era when the frequency of soap-opera broadcasts such as Coronation Street and Eastenders were increased from two to four a week, soap-like hospital dramas (Holby City, Casualty) aired around 50 times a year and slickly produced thrillers aimed at the prime time (Waking the Dead, Silent Witness) were renewed season after season.

Prime Suspect 2 (1991)

“What started as a cottage industry with people working in their front rooms in the 90s became a colossus, where companies were sold for £25 to £30 million,” says Neal, a former head of drama at Channel 4 and Granada. Deregulation of the independent sector during this period had a significant impact: “It became an investment prospect with monolithic studio values, driven exclusively by business.” Whilst there were notable exceptions – Low Winter Sun (remade for US audiences last year) and the political thriller State of Play (turned into a Hollywood movie starring Russell Crowe and Ben Affleck) – the budget and impetus left over to make the kind of drama that had once made the UK the envy of the world greatly diminished. In 2009 an open letter to the industry by Tony Garnett, a producer whose career spans from the ‘kitchen sink’ realist dramas of the 1960s such as Cathy Come Home to the present day, summed up the situation. “If you want to make dramatic fiction for the screen you must first strangle your creative impulses.”

This was a rough era for the UK’s best screenwriters. Allan Cubitt, writer of The Fall and – two decades prior – the Emmy-winning season 2 of Prime Suspect, testifies: “I was frequently credited as an executive producer but all that means is people are compelled to keep you in the loop. You’re not necessarily involved in the crucial things, such as casting or directing, that take the script from the vision in your head to rendering it on screen. People went off and made what seemed to be a diametrically opposed drama to the one I’d written.”

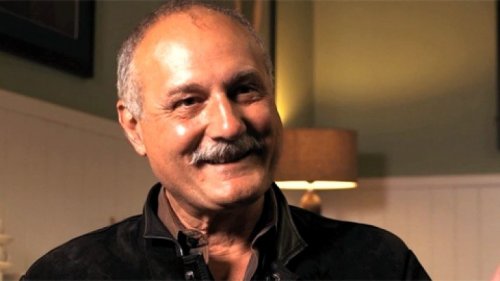

Allan Cubitt (second right) on the set of The Fall.

In today’s world of cutting-edge TV drama, the UK’s content providers are not only competing with their domestic peers but also international ones. Social media will indicate if a new production is a ‘must see’ series as soon as it’s broadcast. With distributors such as Netflix and Amazon making original content, and new entrants into the sector such as Sky and Channel 5 (back to making original drama after a decade’s absence), creating something that viewers will actively seek out amongst the blizzard of choices is increasingly challenging.

In order to create such a production there has been a reversal in how high-end drama is commissioned in the UK. “Scripts for BBC2 must have a bit of danger, something other, and come together in unusual and jagged shapes,” says Ben Stephenson, the BBC’s head of drama. He sees BBC2 as the natural home for the broadcaster’s most daring work: “Some people should absolutely passionately love them while others say ‘What the hell is that? I don’t get it.’ I’d rather something didn’t quite work but had an ambition to be amazing.”

Other providers are equally aware of the nuanced landscape of the industry today. “If the BBC, ITV and Channel 4 are at the top of their game, there’s no point competing with that,” says Anne Mensah, Head of Drama at Sky. “We have to offer something different. It’s about giving customers something they can’t get anywhere else.”

Tony Grisoni

Credit: BAFTA Guru

Braver commissioning is creating an air of experimentation and creativity that now pervades the industry. Preconceptions about the form creators are working in – film, TV or theatre – can be put to one side; a production it must simply be the best it can be. “I don’t work any differently on TV to how I do in film. I don’t feel there is a difference,” says Tony Grisoni, a frequent collaborator of the film director Terry Gilliam, who wrote Channel 4’s Southcliffe, the most nominated drama at this year’s BAFTAs.

The atmosphere of the industry now is more reminiscent of the days when Loach, Potter et al cut their teeth creating one-off plays for the BBC in series such as The Wednesday Play and Play for Today that ran from the early 60s through to the early 80s. Various UK channels have slots for unknown and up-and-coming writers and directors, but Sky’s Playhouse Presents in particular was conceived along the lines of those early series, as a space to cultivate new talent but also to explore the creative facets of individuals who have established themselves in other fields. Its Pavement Psychologist was the first feature written and directed by Idris Elba, better known for his roles as Mandela, Luther and Stringer Bell in The Wire, and the playwright Polly Stenham (That Face, Tusk Tusk) wrote Foxtrot for this strand. And Lucy Kirkwood, the recent recipient of an Olivier award for her play Chimerica, was commissioned by Sky to write The Smoke, one of the subscription channel’s flagship series about London firefighters, despite having previously only written a couple of episodes of Channel 4’s teenage drama Skins. “Nobody questions a decision to commission a centrepiece drama based purely on talent,” says Sky’s Anne Mensah.

The Smoke (2014)

The success of Chris Chibnall’s Broadchurch for ITV underlines the importance of having the writer back at the heart of the creative process, something that now seems a defining characteristic of all the UK’s most ambitious productions. Says Neal, “I hate the attitude in the British production world where the writer is perceived as ultimately irresponsible, who given his or her way will write a scene that’s going to go totally over budget – or that they’re mad and they need to be chained and contained.”

For Grisoni, the experience of creating Southcliffe was an egalitarian three-way partnership between him, the director and the producer. “I wanted the commissioners to trust me, let me wade in and find the screenplay. We got that freedom. The director and I sat down and we started going through the scripts. Together we developed them as actors and crew came on board. I wrote through the shoot so if something didn’t work I could respond.”

For well over a decade US TV drama has dominated international TV schedules and been perceived as too grand in scale for smaller countries to compete with. The costs of creating multi-episode series that run for season after season, and a business model that could afford to offset the costs of pilot episodes that weren’t turned into series (themselves often more expensive than an entire flagship European production), were considered well beyond their means.

Southcliffe (2013)

That was until the Scandinavians (The Killing, Borgen, Wallander) and to a lesser extent countries such as Israel (Prisoners of War, BeTipul) and France (The Returned, Spiral) showed that strongly written series based on original ideas could match or surpass the quality of many US series. The high production values of much of Scandinavia’s recent output were achieved with finance from more than one country (Germany often being a major contributor) without diluting artistic control.

The UK has embraced a similar co-production model on their recent spate of lavish projects. The BBC collaborated with HBO on Tom Stoppard’s Parade’s End and the upcoming J.K. Rowling series The Casual Vacancy. Jane Campion’s Top of the Lake and Hugo Blick’s The Honourable Woman were co-produced by the BBC and the Sundance TV channel. Sky’s Penny Dreadful was a co-production with the US channel Showtime.

The budgets now available to UK producers, coupled with the aesthetic risks being taken, are attracting some of the world’s best talent. Jon Hamm and Daniel Radcliffe made Young Doctor’s Notebook for Sky’s Playhouse Presents. Cillian Murphy and Sam Neill played the leads in BBC2’s Peaky Blinders, and The Honourable Woman was Maggie Gyllenhaal’s first foray from big to small screen. “In Top of the Lake Jane Campion got to make six hours of film – a whole different creative challenge that the film industry is not capable of supporting,” says Stephenson. The BBC’s upcoming projects with the Oscar-winning film director Steve McQueen and a Ridley Scott production starring Tom Hardy typify the level of the UK’s new ambition.

The Honourable Woman (2014)

Co-productions and cross-pollination of international talent could lead to concerns that truly ‘British’ stories made for British audiences (archetypal examples being Boys from the Blackstuff, Edge of Darkness, The Politician’s Wife, The Singing Detective) get overlooked. Even worse, the process could lead to ‘europuddings’, the industry term for a production that by aiming to appeal to many territories succeeds in appealing to none. Mensah believes the industry can avoid this pitfall as it evolves: “Some writers want to write about what’s going on next door and others want to flex their creative muscles and write on a bigger scale. There’s room for both.”

There are blurred lines between how individual countries produce TV drama, but the traditional UK model has the potential to be what differentiates it at an international level, particularly from the US model that many countries now try to emulate. The roots of British TV drama lie in radio and theatre (the BBC’s first TV dramas were simply filmed theatrical productions), built around the vision of a writer or director schooled in these disciplines, whereas US TV drama originated from the movie world.

A typical UK production will last from a single episode to around six (Broadchurch and The Honourable Woman were exceptions consisting of eight), an amount that can conceivably be written by one writer. US series normally last from 10 to 22 episodes and will be overseen by a showrunner, with a contributing team of writers working towards his or her vision. Successful US series like The Sopranos, Mad Men or Breaking Bad are renewed season after season. Writers aim to keep storylines open-ended in the hope their series will be renewed. In the strictest sense the aim of a US TV drama is never to end, whereas a UK production aims to deliver a fully executed, self-contained vision.

Parade’s End (2014)

The traditional UK model arguably offers more authorship and a more idiosyncratic platform that better suits many authors and productions. “I was so saturated, immersed in it, that it was like I found myself in the middle of a nest of Russian dolls,’ says Tom Stoppard, screenwriter of BBC2’s Parade’s End, nominated for both Emmy and Prix Italia awards last year. “TV drama can bring truthfulness off the TV screen, and force of character and emotion into your living room. I never had an experience like Parade’s End, ever.”

Interestingly, the most talked-about US show this year, True Detective, gained a lot of attention because it rejected the typical US showrunner model and adopted what is effectively the UK method of creating TV drama. Nic Pizzolatto wrote all episodes himself and the upcoming second season will have entirely new storylines and lead characters.

The renewed drive and ambition of the UK industry are impressive but for some the more humble rewards it now offers are just as welcome. “Now you can actually judge my writing from what ends up on screen,” says Cubitt.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.