Sylvain Chomet

Director – Belleville Rendez-vous, The Illusionist

I met Takahata Isao in his studio when Belleville Rendez-vous came out. Studio Ghibli had to make bonus features for the Japanese DVD, which they were distributing, and Takahata interviewed me. We sat together in their screening room – a very odd moment – and he asked me a lot of really pertinent questions, as the Japanese do so well.

I found him very warm and mischievous; I’d say he was highly critical, in terms of how he put his questions to me, about American animation in particular and mainstream animation in general. I got the sense that he was an artist with integrity, who saw animation above all as an art, rather than as a business. He was probing himself (as well as me) about the global and commercial success of Miyazaki’s films, and of Studio Ghibli. I was deeply struck by the way he called all this into question. This is, I think, how a great artist goes about things. Another one, alas, who has gone to join the fireflies.

Tomm Moore

Co-founder – Cartoon Saloon; director – The Secret of Kells, Song of the Sea

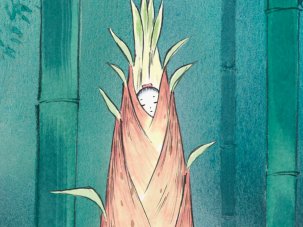

The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013)

It’s very sad to hear of Takahata’s passing. I met him only briefly around the Oscars for The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, which was nominated the same year as Song of the Sea. I continue to be deeply inspired by his work: Only Yesterday, My Neighbours the Yamadas, and of course Grave of the Fireflies are frequent touchstones for us in our work in Cartoon Saloon. When I saw The Tale of the Princess Kaguya in the Winter Garden Theatre in Toronto, I felt it was an amazing testament to the power of hand-drawn animation; the expressiveness and power of simple pencil lines to tell the story and evoke the emotions of the characters has become a major inspiration for me.

As my friend and creative partner Nora Twomey said, any one of his films would be an amazing legacy. It’s amazing that he also founded one of the most influential studios in the world, and shepherded the masterpiece The Red Turtle to the screen on top of his many achievements as a director. His work will continue to inspire for generations.

Michael Dudok de Wit

Director – Father and Daughter, The Red Turtle

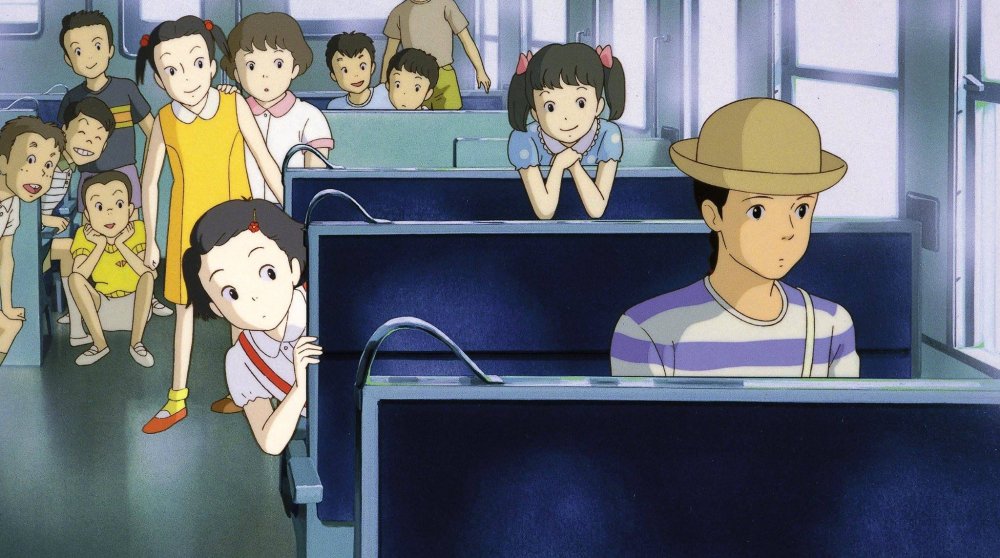

My Neighbours the Yamadas (Hōhokekyo Tonari no Yamada-kun, 1999)

It was the most wonderful experience working with Takahata. We had many long discussions on the finer qualities of The Red Turtle’s story, such as the symbolism and the subtle emotions, and over and over again I was aware of his wise intelligence and his strong intuition. He was very discreet and courteous and in group meetings he would sit quietly, just listening for a long time. Then finally he would talk and get into a flow. Listening to him, it was obvious that I was in the presence of a great master.

Michel Ocelot

Director – Kirikou and the Sorceresss, Tales of the Night

Pom Poko (1994)

The Maison franco-japonaise in Tokyo once organised a little retrospective of my films, and asked me which Japanese animator I’d like to meet. I chose Takahata Isao.

Of all the auteurs of Japanese animation, he had moved me the most. My first experience of his work, of course, was Grave of the Fireflies. I was not only moved by the devastating ending, but also by the human touches throughout the film, which transcended the depiction of a particular country in a particular era. I went on to discover his other masterpieces, all of which had a dual nature: understated in appearance, audacious in fact. I couldn’t believe the insolence of Jarinko Chie (Chie the Brat). I admired the ‘impossibility’ of Gauche the Cellist, an animated feature that is just about learning to play the cello; Only Yesterday, a straight, gentle ecological feast in which dreamy childhood flashbacks provide guidance to the young protagonists; and also the joy and sadness of Pom Poko…

Back then, my first meeting with Mr Takahata was for a public discussion onstage. Though not a very private first encounter, it nevertheless felt somehow intimate. Mr Takahata had never heard of me, but as my films were the focus of the event, he was obliged to watch them. Fortunately, he appreciated them. And then a miracle happened. This great auteur translated the book version of my film Kirikou and the Sorceress for pleasure (he was familiar with the French language and culture); he then oversaw the film’s dubbing into Japanese, which was done perfectly. He pulled off the same feat for my subsequent feature Azur & Asmar: The Prince’s Quest.

After that, we would see each other from time to time, and I can happily say that the auteur I so admired was also a courteous, respectful, generous, cultured, sophisticated man, always a pleasure to be with. I am glad that, before leaving us, he was able to complete The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, another ‘impossible’ film that was too expensive, too long, too peculiar – impossible, brilliant, Japanese.

Jayne Pilling

Teacher and historian; founder – British Animation Awards

Only Yesterday (Omoide poro-poro, 1991)

I have always felt that Takahata was unfairly over-shadowed by Miyazaki. For the record, I will never forget – and be forever thankful for – a time back in 1995, several years before Ghibli had started to have any distribution or make an impact in the West. That’s when I discovered the films of Takahata at a tiny festival in Italy, Cartoombria, whose director Luca Raffaelli had arranged a complete retrospective.

Having admired the pyrotechnics of Akira, but lazily allowing it to confirm my prejudices that anime was essentially ‘a boy thing’, I went to a screening of Only Yesterday out of politeness, and a feeling that, having seen one, I could ignore the rest. And I was blown away. It was the very first time I had ever found a lump in my throat watching an animated film: the delicacy of feeling, the depth of understanding of human psychology and relationships – and particularly in relation to female adolescence! – left me breathless, and I spent the next few days watching every single film. That retrospective completely changed my views on Japanese animation, and started me off on a long and wonderfully journey of discovery. So thank you, Mr Takahata!

Ilan Nguyen

Animation scholar, longtime interpreter for Takahata

Grave of the Fireflies (1988)

More than anyone else, Takahata transformed the language of Japanese animation after the war, insisting that it could be social (even political), tragic, and even deal with moral issues. He reflected deeply on the language of this medium, and put these reflections into practice through countless formal innovations, many of which were then adopted by the industry and became conventions. Foreign animations, such as those of Frédéric Back and Yuri Norstein, also had a direct influence on his films, notably his last features. He always strove to break new ground for commercial animation in his country, refusing to submit to the mannerisms and highly standardised look of traditional cel animation.

As an individual, he was strict, extremely demanding, with a formidably keen gaze and critical sense. He was feared by those around him, but his natural modesty meant that he was far more approachable than most of his colleagues. Being at his side meant learning so much.

His thirst for knowledge was such that his work as a filmmaker sometimes seemed like a mere pretext for research. He was passionate about painting, architecture, music and poetry. He retained his capacity for wonder at the beauty of the world, and knew how to appreciate landscapes, the shifting colours of the setting sun, the special shape of a pine cone… His view of existence can be summarised in an expression he loved, and which can be detected in each of his works, so fragile and clear: joie de vivre.

Xavier Kawa-Topor

Art historian and film curator, Nef Animation

Little Norse Prince (Taiyô no ôji: Horusu no daibôken, 1968)

From his first feature, Takahata was driving major changes in the aesthetic of Japanese animation. The Little Norse Prince (1968) revolutionised feature animation in Japan with its modern compositions, the psychological complexity of the characters, and its endeavour to break free from the confines of children’s cinema. Takahata’s works at Studio Ghibli are wholly centered on creating reality within animation – a major aesthetic challenge. He was a moral voice for animation; his cinema is profoundly humanist, interrogating the choices made by individuals and society. He was a keen observer of people, especially children. He could engage in long debates about art, literature or politics, but took just as much pleasure in everyday goings-on – especially in modest social environments, where he surely sensed a kind of authenticity and spontaneity.

With thanks to Alex Dudok de Wit for curating these contributions.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.