Twenty minutes into Mrinal Sen’s Interview (1971), we accompany the main protagonist Ranjit Mallick (played by Ranjit Mallick) on a Calcutta tram, on his quest for a Western suit for a job interview. A young woman on the tram reads a film magazine. She stops when she sees Ranjit’s picture, doing double-takes between the image and the passenger beside her. Suddenly, he breaks the fourth wall to address the viewer directly. He introduces himself as Ranjit Mallick, an actor working in the film for the director Mrinal Sen.

The moment comes out of nowhere, completely surprising the audience. For Sen, it was essential to involve the viewer in the creative process. As he said in a 1996 interview, “This is a two-way traffic. The spectator has to meet me halfway.”

Born in Faridapur in an undivided Bengal in 1923, Sen came to Calcutta as a student in 1940. His first Bengali-language production, Raat Bhore, (1955) was a commercial failure, but he found success with his second, Neel Akasher Neechey (Under the Blue Sky, 1958), set during Japan’s invasion of China and exploring a platonic friendship between a married Indian woman and an immigrant Chinese worker.

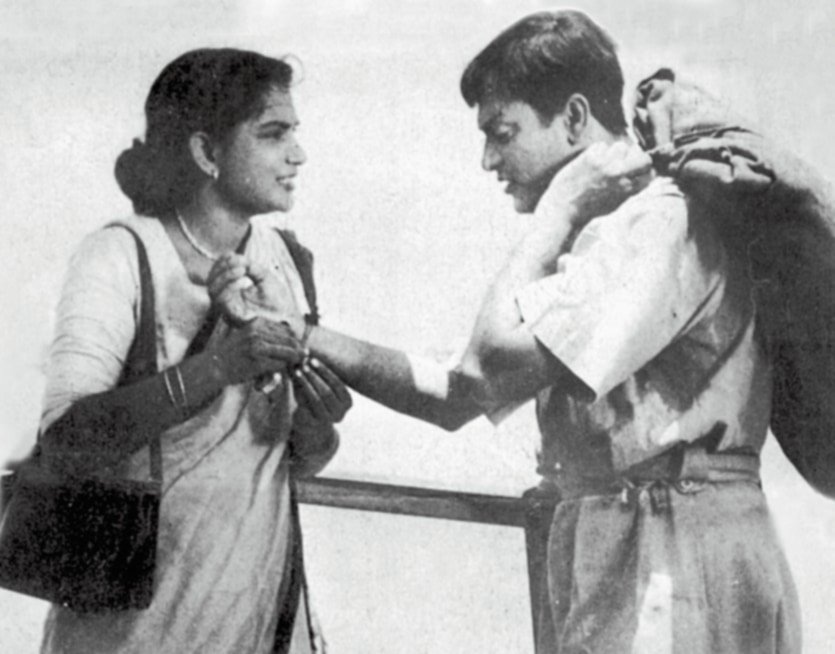

Neel Akasher Neechey (1959)

Both films are strikingly similar in their message of solidarity and internationalism to Dr Kotnis Ki Amar Kahani (The Eternal tale of Dr. Kotnis, 1946), directed by V. Shantaram. Set in the 1930s, like Dr Kotnis, Sen’s Neel Akasher Neechey was released in 1958 when Indian-Chinese relations had soured due to border conflicts. While a commercial success, the Indian government was uncomfortable with its political message in the lead-up to the India-China war of 1962 and it became the first film to be banned in independent India. Discussing the three-month ban in his memoir Always Being Born, Sen wrote, “Even Nehru liked the film and remembered it for quite some time. Most possibly, he liked the film for its content, which unequivocally espoused that our struggle against the colonial rule was inseparably linked with the democratic world’s fight against fascism.”

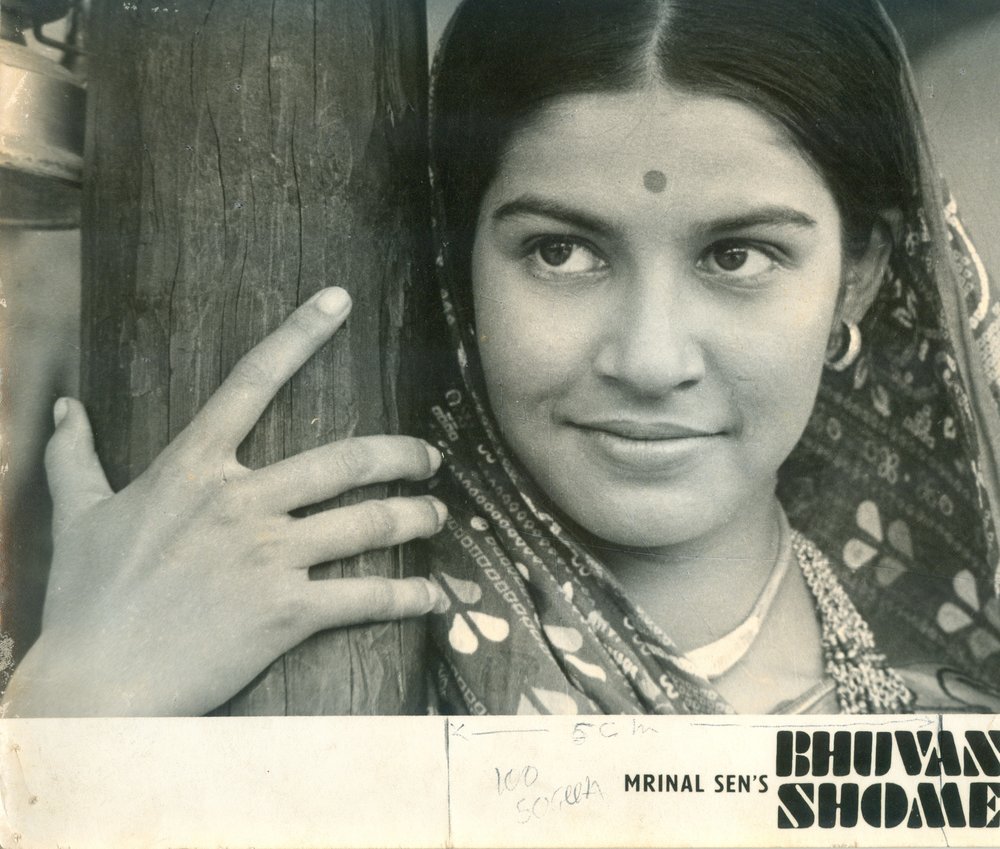

Satyajit Ray’s international success in 1955 made government funding available for non-commercial and experimental Indian films. Sen’s Bhuvan Shome (1969) was a beneficiary of this, telling the simple tale of a hardened jobsworth (played by Utpal Dutt) in late middle age, working for the Indian railways. During a hunting expedition in the inhospitable rural landscape of Gujara, Shome is left a changed man after he meets a charming young woman (Suhasini Mulay, in her debut performance).

Suhasini Mulay in a poster for Bhuvan Shome (1969)

The uncluttered premise allowed Sen to experiment with visual flourishes, freeze-frames, animated sequences and strikingly bold vistas shot in the windswept vastness of Gujarat’s desert dunes. Audiences were also introduced to Amitabh Bachchan as the off-screen narrator of Bhuvan Shome’s knowing voiceover.

Sen received the National Film Award for Best Feature and Best Director for the film, alongside international recognition as the pioneer of the Indian New Wave. Ray famously summarised Bhuvan Shome (to Sen’s annoyance) as “Big Bad Bureaucrat Reformed by Rustic Belle”, attributing its success not to its unconventional aesthetics but rather to things it had in common with popular cinema: a beautiful female lead and a picturesque setting. This incident characterises Sen and Ray’s complicated relationship, sometimes playing out as wars of words in print.

Sen’s films that make up his Calcutta trilogy – Interview, Calcutta 71 (1972) and The Guerilla Fighter (Padatik, 1973) – document and respond to the Naxalite upheaval in Calcutta in the 1970s, in varied ways. Freeze-frames are weaponised by Sen in Interview, as shots of Mallick’s handsome urbane lead are jarringly interspersed with scenes of impoverished children. In using images of poverty, Sen never stopped interrogating his own position and privilege as an urban filmmaker. The Calcutta trilogy in particular underscores his absolute rejection of representations of poverty as somehow dignified, and his refusal to let the Indian middle classes off the hook for benefiting from a colonial legacy of social inequality.

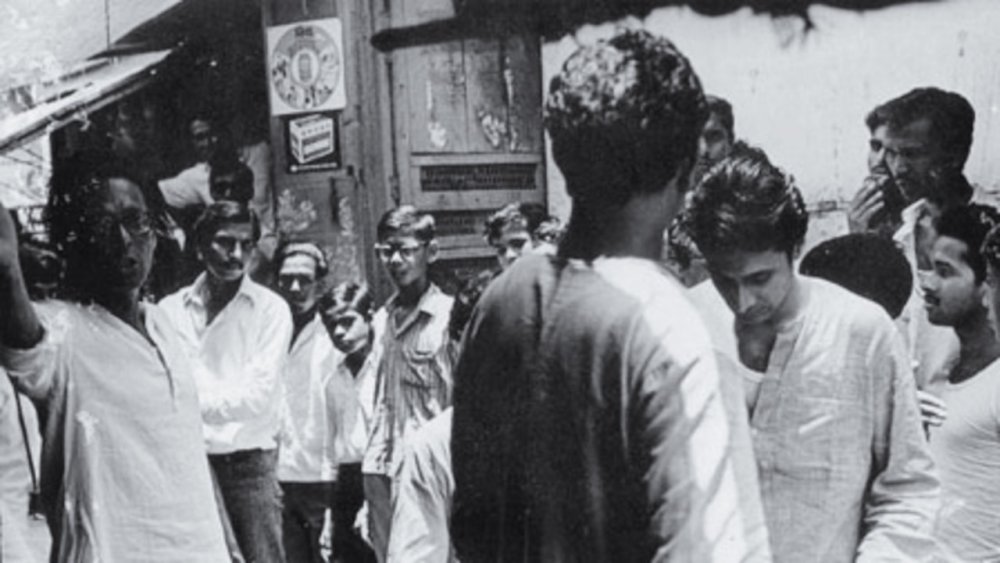

The Guerrilla Fighter (1973)

Sen met his lifelong partner, actor Gita Shome, in 1946 on a film shoot and they married in 1953. Sen often spoke of her crucial role in his career and acknowledged her as his collaborator. The couple are survived by their son, Kunal Sen.

Sen’s work deserves wider recognition for his unflinching political and social gaze, but in his films he’s also capable of extraordinary sensitivity. By the end of Bhuvan Shome, we find the arrogant bureaucrat on the hunting trip, now tamed. Ready to return to his natural habit, Shome gently cradles a bird he’s shot but wounded, which he then sets free. This was Sen’s gift, to never lose sight of the human within the radical.

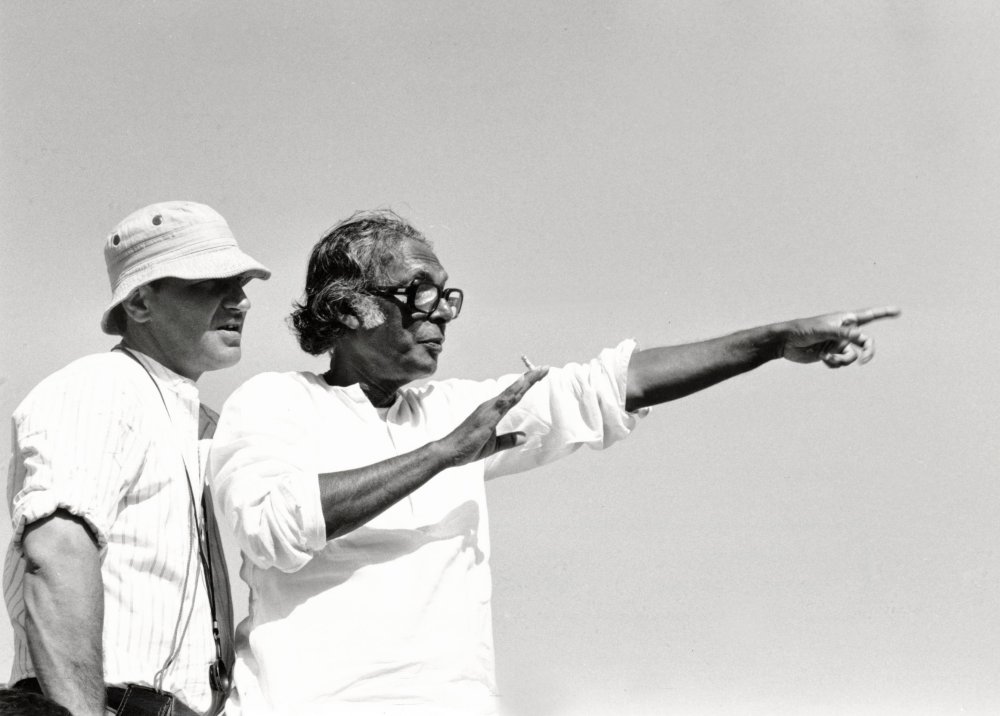

Mark Cousins on Mrinal Sen

When the great Indian filmmaker Mrinal Sen died recently, I felt guilty. Years ago I tried to do a retrospective of his films, but gave up because the prints were in a bad state. More than this, I felt guilty because I’ve seen just six of his 34 films.

I could explain my lack of knowledge of his work on the bad of prints, dearth of DVDs and scant distribution – and indeed I point the finger of blame at our Western film culture for showing so little interest in him – but I’ve long said that my ignorance is my best friend. I force myself into it, this fog, this blur, this terra incognita. I suspect many of you reading Sight & Sound are not experts on Sen either, so we’re in the same place. Let’s flip our ignorance into a positive. Let’s resolve, now that he’s dead, to try to get to know Mrinal Sen’s films.

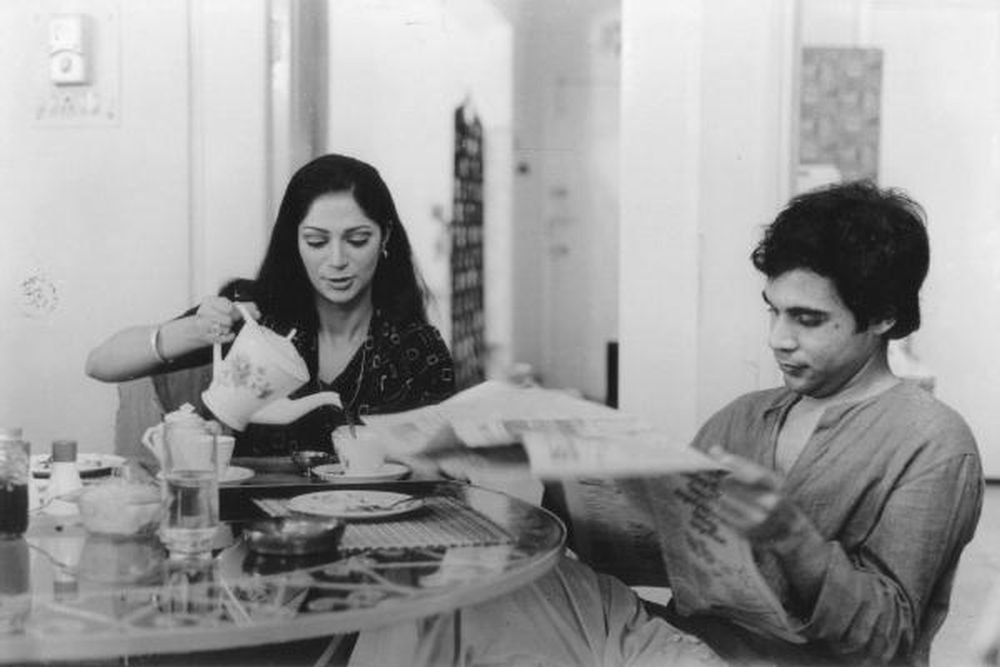

Bhuvan Shome (1969)

Where to start? Here are eight things I know about him, that attract me to him, that entice me:

First, sound. He loved electronic scores, atonality, and sonic modernism. When I first saw Sen’s tenth film Bhuvan Shome (1969), a ludic comedy about a government employee who sets off on a shooting trip, I loved the wildness of the soundtrack. In the 1970s, he was as bold as Jean-Luc Godard in sound.

Second, homes. Sen loved theatre and literature, and many of his films have August Strindberg-like domestic settings. He was interested in homes as prisons, as microcosms, as poetic places. I don’t know if he read Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space, but he didn’t need to. He got the nooks and crannies of domesticity.

Third, internationalism. In the 60s and 70s, Sen’s films were shown abroad, so he travelled and made friends with filmmakers like Lindsay Anderson. Not only did he enjoy the connection to like-minded directors, he had the chance to see poverty elsewhere. In a recent interview on Indian TV, he said “poverty is the same everywhere. It has no colour, no character.”

The Guerrilla Fighter (1973)

Fourth, it’s striking how often his films were shown in the Cannes Film Festival – in all its main sections. Cannes showed more of his movies that those of Satyajit Ray, the Indian director that most movie lovers have heard of.

Fifth, there’s the issue of women in his films. He created many great parts for female actors, and women wanted to work with him, and loved doing so. In a number of his films, though, a young woman is idealised, projected upon. Could this be a weakness in Sen’s work?

Mentioning that brings us on to the last three, most political, elements in the cinema of Mrinal Sen. There’s a powerful concern with the everyday, which links back to Italian neorealism. In his beautiful film Interview (1971), a guy tries to get a business suit so that he can do a good job interview, a scenario right out of Cesare Zavattini (or Ken Loach).

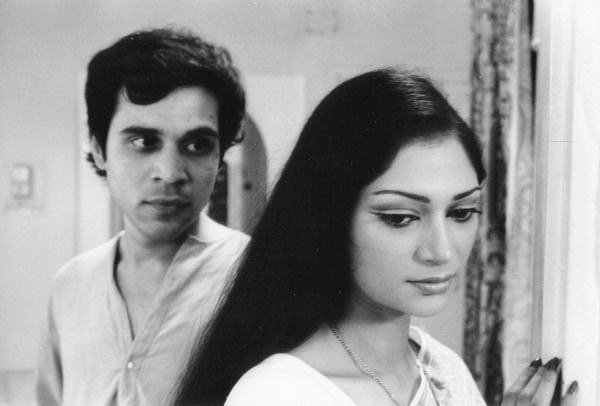

Interview (1971)

The seventh theme in Sen’s cinema is all pervasive – his Bengali-ness. He was born in what is now Bangladesh, and so many of those houses that I mentioned earlier are Bangla – downstream from Rabindranath Tagore. Calcutta/Kolkata was Sen’s crucible, his inspiration, his rock pool. The music, literature, decor and urbanism of West Bengal suffuses much of his cinema. He was less acclaimed in the West than his fellow Bengali Satyajit Ray, and less radical visually than another great Bengali director, Ritwik Ghatak.

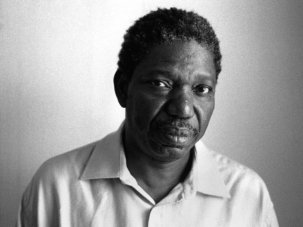

The last and eighth aspect of Sen is the most political: his relationship to what was known as Third Cinema. As you’ll know, Third Cinema was neither commercial filmmaking (Hollywood and Bollywood), nor art cinema. It was a third thing – broadly Marxist, not made in Europe or America, and inspired by cultural debates in South America and elsewhere. Sen knew Cuban director Santiago Alvarez and noticed the role that film was playing in Cuba, and in West Africa – consciousness-raising, oppositional, using the accessibility of film to engage the people in poor countries who would most benefit from left wing politics.

Third Cinema wasn’t a genre, it was many genres. Sen was one of the great figures in Third Cinema. He somehow saw cinema as literature and a weapon. His films are being restored. Let’s get them widely seen.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.