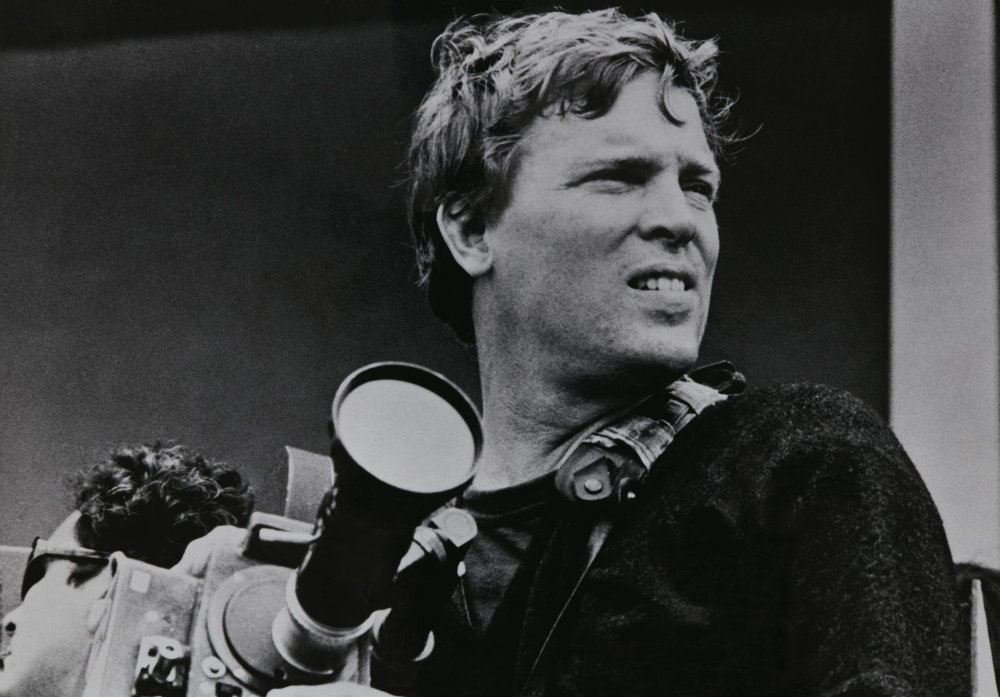

There are many filmmakers who are admired for their work. But few can claim to have created a genre of their own. Donn Pennebaker (‘Penny’ to his friends) was one of those. I can still recall the impact of seeing his handheld observational films, with long takes and no commentary – made with his collaborators Robert Drew, Ricky Leacock and Albert Maysles. These were cinéma vérité documentaries, which were as revolutionary as the Modern Movement was to architecture, or cubists were for painting.

And like those other artforms, this revolution was prompted by technological progress: the development of handheld cameras that also recorded sound along the side of the frame, or with a cable to handheld recorders that would be in synch with the cameras, and could capture dialogue as it happened.

Before then – and for a good few years afterwards – most documentaries were shot on mute handheld 16mm arriflexes or with bigger cameras on tripods. Sound was recorded separately from the cameras. The final films relied on loads of music and narration – what was known as ‘the voice of God’ telling you what you were seeing, as well as what to think about it. There were some fine films made that way, by the likes of John Grierson and Humphrey Jennings in the UK and Robert Flaherty in the US, among many others. They were “film poetry”, as Grierson once told me accusingly when criticising observational documentaries – ‘obdocs’ – for lacking it. But for me and many other young directors, the unvarnished reality of the cinéma vérité films was truly dramatic, and inspiring.

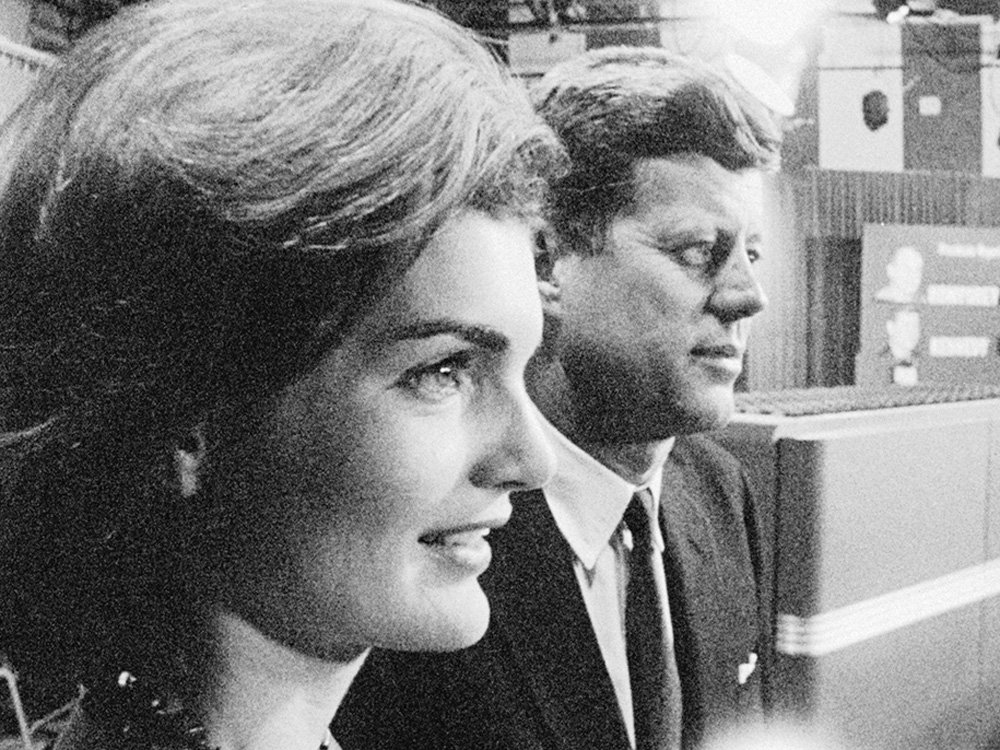

Jackie and John Kennedy in Primary

I was a young theatre director at the time. I had been an observer at the Actors Studio in New York, and had been fascinated by the task of conveying a sense of reality on stage. That was the goal of the Method, taught to many film stars and directors by Lee Strasberg. Seeing my first cinéma vérité films made me realise that this was the best possible way of capturing reality, and conveying it to an audience. I switched from directing plays to making documentaries, thanks to those films.

One of the first was Primary (1960). Pennebaker and his colleagues completely blew open several forms of filmmaking. Their first political film was for the Time-Life film unit headed by Drew. It was shot during the battle for the Democratic party presidential nomination between John F. Kennedy and Hubert Humphrey. Unlike the polished and prepared normal coverage of politics and current affairs, it showed real people engaged in a real and chaotic struggle – raw, obviously filmed as it happened, with all the unexpected excitement of knowing that neither the filmmakers nor the participants would know what was going to happen next.

That remains the secret ingredient of observational filmmaking. It can turn ordinary life into drama, knowing it is real and unstaged. As a director and cameraperson, you give up the control normally available, the power to decide and compose each shot carefully, and light it if necessary. You give up the chance for retakes, or the ability simply to stop when things go wrong and resume where you were before. Your task is simply to keep going wherever the action you are following takes you. It is a high-wire act, especially when following fast-moving and fast-talking characters like politicians running for office. And without properly audible recorded sound, you have nothing. In pure vérité films, not having synch sound renders the pictures worthless – no matter how poetic they may be.

The Energy War trailer

The Pennebaker team went on to make a huge variety of films on subjects not normally conceived of as film-worthy: like people in offices doing business, as seen, for example, in The Energy War (1978) about Jimmy Carter’s gas bill (which Penny kindly told me years later was inspired by my film Decision: Steel for ITV earlier in the decade).

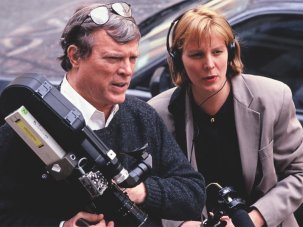

More than three decades later, Pennebaker ― alongside his wife and frequent collaborator Chris Hegedus ― directed another bombshell for political filmmaking. The War Room (1993), which went behind the scenes of Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign, revealed the machinations of election-strategy-making and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

The War Room trailer

But the other major accomplishment and engine of cultural change devised by Pennebaker and his collaborators was the filming of pop music, again as it happened, along with fascinating and revealing footage of what happened behind the scenes. His astonishing feature-length film of Bob Dylan’s 1965 tour of England, Dont Look Back (1967), still feels utterly contemporary for the raw honesty of the filmmaking.

Far from being a hagiographic puff, as so many more recent apparent portraits of pop stars must be, tightly controlled by the star and their PR machine, Dont Look Back is an unvarnished portrait of a brilliant and self-involved artist. In one revealing and memorable scene, Dylan totally ignores the magnificent singing of Joan Baez in their hotel room, while banging away on his typewriter, only barely swaying in time with it after many minutes have gone by.

The Freewheelin’ Music Documentary: D.A. Pennebaker Looks Back at Bob Dylan and Dont Look Back by Leigh Singer for Sight & Sound

The film is remarkable for the length of takes and sequences, which are far longer than most editors and directors would tolerate then or now. The richness of each take is that it develops a life of its own: like the verbal fencing with a hapless student journalist who is tied in knots by Dylan’s relentless banter. It if were shorter, it would have just been witty. At the length Pennebaker shows it, we see Dylan as cruel, picking the wings off a butterfly. Given that the length of each film magazine was ten minutes, the investment of so much time in each take without a cut is even more remarkable. (In the UK, the work of Kim Longinotto shows a similar willingness to keep rolling to follow the action unfolding.)

The filming of Dylan’s concert performances is also lengthy, and more rewarding for being so. Pennebaker’s magnum opus in that vein was Monterey Pop (1968), with precious examples of late lamented singers like Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix. It is so beautifully filmed in colour that it feels like we are there at the festival and is as powerful and enjoyable as when it first burst on the scene.

Monterey Pop trailer

The power of the film and its hugely long takes stands in stark contrast to the restless coverage of such concerts seen in the successors to Monterey Pop – marked by kaleidoscopic filming and nervous editing – and in the still more hysterical form, the pop video. Pennebaker trusts his audience to sit still and immerse themselves in the experience – as it happens. The ending follows the set by sitar master Ravi Shankar and goes on and on, far beyond our expectations: just as the music doesn’t follow Western melodic forms, so Pennebaker holds on the performance rather than truncate it. It is an act of love to devote such time to the music, the musician and the occasion.

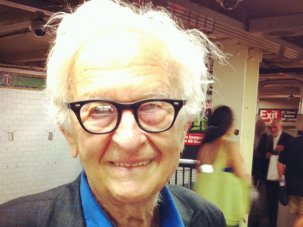

He leaves a lifetime of insight and achievement, always accomplished in a disarming way. All of us observational filmmakers – and his audiences – owe him a great deal, especially at a time of the manipulation of imagery known as fake news. Penny’s films demonstrate a commitment to the honest depiction of reality, without artifice or interruption, and a trust in the audience to value it, that is desperately needed now.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.