Guy Maddin’s The Forbidden Room at the IMAX: the emulsive, libidinous shapes of lost narrative fragments conjured up by Canada’s most effervescent imagination on the screen that usually hosts the likes of Skyfall and Godzilla. Such was the ambitious gamble of the London Film Festival Experimenta gala (presented by Sight & Sound) last Friday, and it was great to see it had been met with such enthusiasm: the auditorium for the biggest screen in Britain was packed and brimming with anticipation for this most unusual filmic experience.

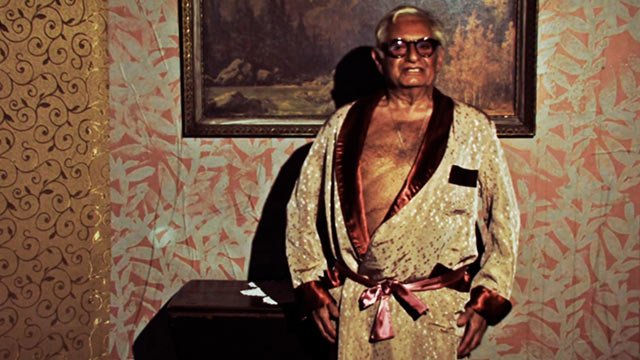

The Forbidden Room evolved out of Maddin’s Seances project, in which he and co-director Evan Johnson made lost or unrealised films, shooting them in public at the Pompidou Centre in Paris and in Montreal’s Phi Centre. After an introduction in which Maddin and S&S editor Nick James bandied Film Comment’s description of the film as being “akin to a brain aneurysm” – but “in a good way” – the delirious deluge of hyper-kinetic fevered dreams was unleashed. We watched doomed submarine sailors looking for their missing Captain, lumberjacks and wolfmen fighting over an amnesiac temptress, skeleton women and Filipino vampires luring souls to their perdition, a virgin sacrificed to an erupting volcano, a squid thief, a lost socialite and a lobotomised derriere-obsessive all collide and melt into one another, interspersed with literary quotes and silent-style intertitles, the whole framed by an educational film in which a hairy-chested old goat in half-open robe gave incongruous instructions on how to take a bath.

The Forbidden Room (2015)

Although the film was made digitally, Maddin and Johnson managed to imbue it with the lushness and texture of the Maddin’s work of old, the saturated colours and artificial exoticism reminiscent of Careful (1992) in particular. But while it was exhilarating to see the insane beauty they created on such a large screen, it grew apparent that the IMAX may not be the most appropriate place for such a relentless visual and sonic bombardment, and the intense sensory overload of the film would probably be better served by a more conventional screening setting. Nor, despite Maddin’s charmingly maniacal desire to make as many lost films as possible, was the film helped by a running time of over two hours: it could do with a trim and a stronger structure. Once the physical discomfort of the screening was safely past, however, what remained branded upon the brain was The Forbidden Room’s ecstatic pleasures.

After the film, Maddin returned to the stage and regaled the audience with his idiosyncratic brand of humour, at once wittily erudite and salacious. Asked about his use of colour, he talked about being inspired by Technicolor movies, in particular Douglas Sirk’s, and his habit of giving name to their colour palettes as he watched them: instances included “aqua velvet”, “lemon chiffon” and an “orgy of off-whites” – not to mention “Rock Hudson’s nipple”, aka a sort of “smoky rose”.

The Forbidden Room (2015)

The obsessiveness that fuels his art filtered through as he lamented not being able to remake all the lost films he discovered, his biggest regret being the frustration of his project based on Brad Grinter’s 1974 sexploitation flick Never the Twain, about a man possessed by the spirit of Mark Twain at a Miss Nude World pageant. In Maddin’s wondrously warped interpretation this would have been combined with Euripides to end with “100 naked women slaughtering patriarchy”, and shot on the multi-directional camera used by fellow Canadian experimenter Michael Snow for La Région centrale. Someone please give this man some money.

Most fascinating of all was the revelation that the educational film that frames The Forbidden Room was written by the poet John Ashbery. Maddin asked him to rewrite a lost Dwain Esper sexploitation short, which compared how a married woman and a spinster would take a bath. Ashbery reimagined this by way of the fancifully formalist French literary inventor Raymond Roussel, and the skewed result is one of the most absurdly pleasing fragments of the film.

Watch Guy Maddin’s LFF Connects talk with Clare Stewart

The following day, BFI Southbank provided a more intimate setting for Maddin’s LFF Connects discussion. With the ‘ectoplasmic glooping’ from Seances as backdrop, the director described in more detail the lost films he had wanted to make: films by blacklisted directors, pro-Nazi films, anti-Stalinist films, Yiddish films; an unrealised Leni Riefenstahl film based on a play by Heinrich von Kleist; the first feature film made by a Bolivian woman; numerous lost Filipino films, especially in the vampire (aswang) genre; Cambodian films destroyed by the Khmer Rouge, who also murdered their nation’s directors in the 1970s. Poignantly, Maddin talked about his desire to include Native American films to outline the way they have been treated, something that proved impossible because Native Americans were never able to make films. Through all of these types of loss he wanted to create a “shape of loss”, a poetic and lovely idea that helped justify the length of The Forbidden Room.

The origin of the Seances project came when Maddin was asked to ‘haunt’ the newly opened TIFF Lightbox in 2010 to give the brand-new building some film history and a few ghosts. For the 11-piece installation, he decided to make lost films by some of the directors he adores, including Kenji Mizoguchi, Josef von Sternberg, Fritz Lang, Alice Guy and Oscar Micheaux.

He also shot short films not connected to specific directors, and two of those were screened as part of the talk. Bing and Bela was typical Maddin madcap macabre: a young woman cannot decide who to mourn between Bing Crosby and Bela Lugosi – a story prompted by Maddin’s discovery that two of his favourite performers are buried side by side in Holy Cross Cemetery in California.

The other, Sinclair, was a much more sober and elliptical film of a man in a waiting room, shot with Michael Snow’s multi-directional camera. The three-minute loop was inspired by what had happened to Brian Sinclair, a Native American man who had died in hospital after being left to wait for 33 hours: another type of loss, as Maddin affectingly described it.

Maddin directing one of his Seances

The Seances project invited the spirit of a lost film to possess its actors, and the parallel between the invocation of spirits and cinema is at the heart of the project: in both, Maddin said, “you’re being shown that which is not there, to enchant you, and you want to believe it’s there.” This is the director as charlatan, “manipulating people to charm them,” he continued – the director as showman, too, as he had earlier described himself. The heightened time of the two gatherings also revealed Maddin the megalomaniac creator, Maddin the polymorphous pervert, Maddin the film poet, Maddin the enchanter. Between Friday night and Saturday evening we saw them all, and this (con) artist’s act of filmic spiritualism had us all beautifully fooled and thoroughly bewitched. But as he claimed to be now ‘cured’ of this particular obsession with the lost, prepare to be deliciously deluded by another form of deviant cinematic illusionism in his next magic lantern show.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.