The British cinema has recently been moving towards greater independence, a freer hand for the enterprising producer and a wider range of subject. A young artist here, though, would still encounter enormous problems in trying to make the ‘nouvelle vague’ type of film, produced very cheaply, with total independence, and outside the traditional system. Walter Lassally, whose experience as a cameraman ranges from British documentaries and features to Michael Cacoyannis’s A Girl in Black (1955) and the Pakistani feature Day Shall Dawn (1958), here considers some issues of independence.

In the spring of last year I was approached by a young American playwright to shoot his first feature film in Britain. Norman Vane had written several plays, such as Harbour Lights, produced on Broadway in 1956, and The Deserters, currently touring Britain in repertory, but was quite innocent of any knowledge of the British film industry from the inside. The story of the projected film appealed to me: it was basically a love story between a young girl and a hunchbacked boy, set against the puritanical religious background of a Nova Scotia fishing community; its main cast numbered five and its only sets were a bedroom, a cafe and the interior of a small cabin cruiser. It was neither highfalutin in tone nor lacking in action and drama. In short, it seemed to be a good bet for a small-scale production.

The author had about £5,000 backers’ money available to him, but was informed that this would not be enough for a production, even outside the system. At that time, he was reluctant to go within the system since he felt it unlikely that he would be able to retain control over the subject or to direct it himself. While the search for an additional £5,000 proceeded, I approached the technicians’ union and asked how they would view an attempt to make such a film outside the system, with a small unit and in Ireland. I was informed that the union had just spent a considerable sum of money to get organised in Ireland and that they considered it part of their territory. Accordingly, they would resent, and probably resist, any endeavour to make a film there which did not conform to their rules.

When the National Film Finance Corporation was approached for a loan, its spokesmen declared themselves willing to put up the remaining £10,000 on a total budget of £15,000, but were dubious as to whether £15,000 represented an adequate budget for the production. They also insisted on a Completion Guarantee – a form of insurance that the film will be completed, whatever the circumstances, so that the investors will not be left in the lurch. A film accountant was found to go over the budget, and this now rose to £17,500. The Completion Guarantors were willing to co-operate, provided a producer with experience in this type of film was engaged, and one was approached on the basis of a list they supplied.

Neither the NFFC, nor a distributor who was approached, were now anxious to go ahead on the higher budget, however; and when this was once again revised, with the addition of all legal and financial charges which an outside-the-system production might have dispensed with, it rose again, this time to £19,200. It should be explained here, incidentally, that since most of the financial and insurance charges are worked out on a percentage of the total budget, the addition of a single item to the direct cost (such as an extra electrician or an extra day on location) raises the whole budget by a sizeable sum.

Mr. Vane’s inclination at this point was to raise as much money as he could on top of his original £5,000 and to proceed with the picture outside-the-system in Ireland, intending to bring back on this money at least all the visuals and then to find further finance for the post-synchronisation and editing on the basis of this material. He was warned, however, that (a) no union shop would agree to post-synch material for which a ‘guide track’ had not been shot on location by union technicians; (b) that distributors might be very wary of taking his film, however well it turned out, since it would have to compete on their lists with productions in which they had money invested and which would therefore receive preferential treatment; and (c) that it was doubtful whether the film would count for British quota.

In view of all this, the backers felt that an outside-the-system production would be too great a risk, and no more money could be raised. The film was thus thrown back into the system; and finally a distributor was found who was willing to provide 70 per cent of the finance on a £20,000 budget. Working with the producer who had been recommended to him, Mr. Vane proceeded to make his film. (My own involvement, incidentally, had ended before this point, as I was by this time working on another project.) He had a four-week location and a two week studio schedule; he was allowed a free hand with casting and found two very good youngsters to play the main parts. When shooting had been proceeding for a week, a telegram arrived from the union permitting him to direct the film. The agreed schedule proved inadequate, however, and he found himself forced to shoot plot material predominantly, at the expense of atmosphere. Only by claiming that he was shooting title backgrounds, for instance, was he able to get a long-shot of the location town.

At the end of his six weeks, Norman Vane had all the vital plot material in the can; and fortunately much of the location shooting was intrinsically atmospheric. But he was already £200 over budget and was forced to halt. He cut his material to a 90-minute version and showed it to the distributor. “Too long,” they said, “it won’t hold.” This is a phrase which still rings in his ears, as he heard it incessantly in the cutting room and the viewing theatre. Little by little, he was compelled to concentrate his film on ‘plot’. When they finally insisted on making it into a 65-minute second feature, he walked out. Second features are in great demand by the cinemas and also get what amounts to double ‘Easy Money’, the subsidy made to producers by way of the British Film Production Fund. A highly sentimental music score was fitted to the film, although the director protested, and it was then delivered to the distributor. It is called Conscience Bay and it can soon be seen making its way round the cinemas of Britain.

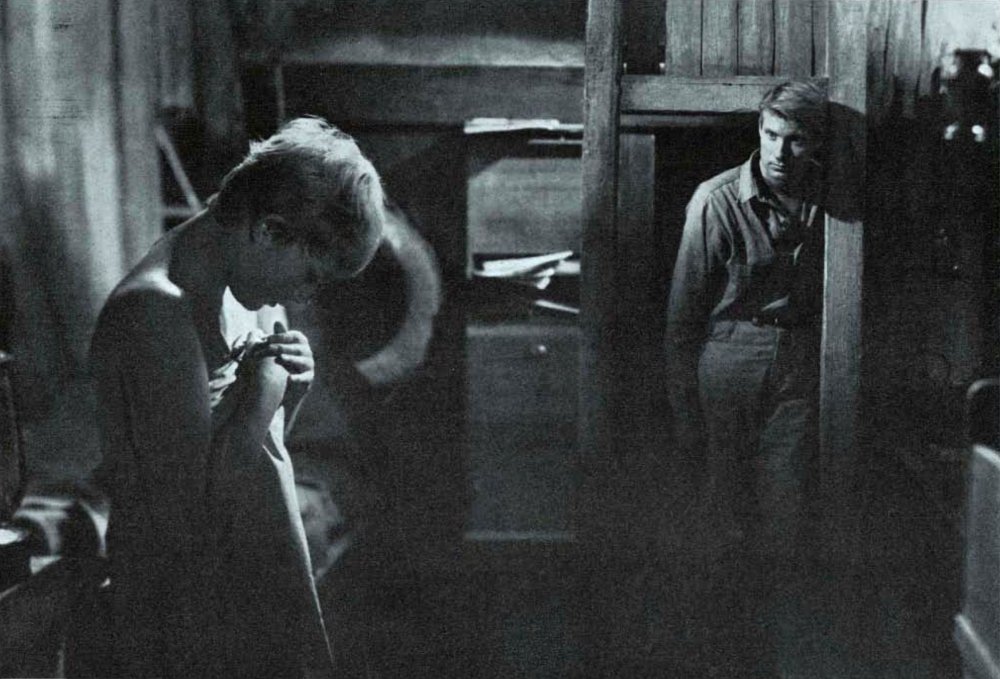

Rosemary Anderson and John Bown in Conscience Bay

What is left of the original idea? Some fine location work, a charming and a capable performance on the part of the two leads, and the bones of a plot which was once firmly rooted in its locale but which now takes place, rather confusingly, in a virtual vacuum. Some of the scenes considered the best by the director have been cut. They ‘wouldn’t hold’. Some scenes, which he thought the worst acted, and had seen fit to remove without injuring the storyline, have been put back. In short, a sorry sort of compromise, which will now perforce be sat through by the audience in the same state of semi-conscious torpor in which most second features are viewed. Will the investors get their money back? Probably…

2

I have not cited the example of Mr. Vane because I have any axe to grind on his behalf, and I don’t want to seem to be putting the claims of his film too high, or to suggest that all the right was on his side. But the history of Conscience Bay is a characteristic one; and there is a lesson here – many a lesson.

For years now I have been closely involved with the often heartbreaking attempts of fresh young artists to begin working in the film medium. What in fact has happened is that these artists are no longer quite so fresh and certainly no longer quite so young. Anthony Simmons, the director of Bow Bells and Sunday by the Sea, both highly praised, and prized, short films, has mainly worked on sponsored documentaries and TV commercials after spending two years trying to set up the feature project that was close to his heart. Gavin Lambert found his interesting, independently financed first attempt at a feature, Another Sky, virtually unsaleable in this country and went to the United States, where he has recently scripted Sons and Lovers.

Lorenza Mazzetti, whose distinctive talent is apparent in Together, left England for her native Italy after unsuccessfully trying to get an excellent story about Teddy boys financed in this country. The censor said at the time that he would object to any treatment of the subject which did not condemn them. Lindsay Anderson, who co-directed the Academy Award-winning Thursday’s Children and whose Every Day Except Christmas earned Britain a Golden Lion at Venice in 1957, is now working in the theatre after the failure of many an attempt at realising a feature film project.

And should it be thought that, as a result of Room at the Top and subsequent developments, the climate has miraculously changed, there is the highly topical example already quoted. Mr. Vane himself, incidentally, is turning his latest subject, a story of the Chelsea set, into a play…

It goes almost without saying that I fervently hope The Entertainer and Saturday Night and Sunday Morning will prove forerunners of a healthy new movement. But if I had to summarise in one phrase what a potential British new wave would be up against, I should say: the Dead Hand. The Dead Hand of apathy, of complacency and convention, whose grip is felt on all sides of the industry. In distribution it is manifest in the assumption that only what has been successful in the past can be so now and in the rigid compartmentalisation into first, second and co-features, each with its strict formula for casting, budget and schedule. In finance it is manifest in the attitude that films are a product not so different from sausages and in the rigidity of its system, which makes it very difficult for really independently financed films (such as many of the French nouvelle vague productions) ever to reach the screens of this country.

In production it is manifest in the attitude of the majority of technicians, in their obsession with ‘professionalism’, in their suspicion of any director entering the medium from ‘outside’ (i.e. from the theatre or novels), and in certain inflexible attitudes of the union, which still sometimes clings tenaciously to the past. It is apparent in the reluctance to shoot on location and the inability to do so without the paraphernalia associated with a large unit; in the emphasis on polish, on strict continuity, on smooth cutting and cold, glamorous camerawork at the expense of invention, of spontaneity. Mr. Vane, for example, had to cut a shot just because the letters R.A.C. appeared in tiny print on the side of a vehicle instead of R.C.A.C.

Perhaps the most serious manifestation, though, lies in the current exaggerated emphasis on pace, sometimes at the expense of atmosphere, poetry and emotional involvement. This relatively new vice in British films was referred to in the review of The Angry Silence in the last issue of Sight & Sound. Almost to a man, British film editors now insist on creating artificially whipped-up pace in the erroneous belief that audiences will somehow be bored by a slower moving story. Of course, many films are so bad that the sooner they are over the better for everyone; but a good film will always be able to hold its audience by involving it emotionally, and the pace should arise naturally out of the mood of the story. How would L’Atalante or Pather Panchali look if they were edited according to the current British practice?

John Osborne and Tony Richardson, writing some months ago to the Sunday Times about an article called The Cinema Tycoons, commented: “We believe that the best way to make adult films is to give the maximum of independence to those immediately, creatively concerned. Both the belief and practice of many film producers in England is in entrenched opposition to this approach… Very few people,” they sadly added, “can be persuaded to make uncompromising films on small budgets.”

Richard Attenborough and Donald Houston in The Man Upstairs, one of the few small-scale British productions of recent years which has risked originality. The film’s press was very good; its box-office returns, reportedly, were not

No one who has not actually worked in the studios will be able to realise how deeply ingrained is the attitude of the Dead Hand, how every attempt to breathe vitality into a film is apt to be met by the conventional objections: it won’t cut; it won’t match; it won’t hold. How often one hears these reiterated phrases from people who hold professionalism dear, but whose rigid adherence to set formulae of doubtful validity might suggest that they are not acquainted with many of the masterpieces of the cinema.

3

Cavalcanti, writing in Film Monthly Review 11 years ago, said: “The big films made since the end of the war are the reflection of a tired world – their themes lacking courage, their technique lacking imagination, their treatment lacking poetry. Our films are made by contract. To make a film is no longer an artistic adventure. There is no longer any experiment, even in the documentaries. There is no opportunity for youth.”

Lamentably, this is not a great deal less true now than it was then. Britain lacks enterprising producer-impresarios, men who have a nose for talent, an ability to select people who will work well together and stimulate one another, and a capacity to act as a bridge between the artist and the financier. Two such impresarios existed in Britain just after the war. One is dead; the other is no longer a film producer.

No one blames producers for being cautious or investors for wanting to recoup their investments; but films are not just ‘made by contract’ and one of their essential ingredients is ideas. One film of the calibre of Citizen Kane brings in enough new ideas to keep the run-of-the mill productions rolling for some years; and to neglect one’s most essential raw material is surely a foolish policy in any business. A film industry that is run by accountants on efficiency expert lines is like a bakery that forswears the use of dough.

Many people in the trade suspect that the writers of Sight & Sound would like to force highbrow films down the reluctant throats of an unwilling public. This is as ridiculous as it is impossible. Speaking personally, I do not even believe that the raising of standards of audience taste is something which can be accomplished on a mass level. But it is intolerable that a handful of people in the distributors’ offices should be the arbiters of public taste, when they have been proved wrong so often, having been guilty of so many misjudgments, and when they are so reluctant to give the public a real choice. Distributors might consider the financial success of the nouvelle vague in France, where backers have realised that if only one film out of six cheaply made hits the financial jackpot, they are still a good deal better off than if the one expensive picture they might have made with the same money shows itself a dead loss.

In the long run it is ideas rather than gimmicks that are needed; and before ideas can get a foothold the Dead Hand must be lifted. Let films be any length within reason and programmes be based on intelligent juxtaposition and elementary mathematics. If we must have double feature programmes, then at least let the second feature field be a training ground in which new directors and writers are really given a chance and in which the limitations of length and budget act as a healthy discipline, not a millstone as at present.

Let technicians admit that to experiment is to be alive and that to play safe means ultimate death to the medium. Let the union diehards realise that to stipulate a four-man crew for a piece of apparatus which an intelligent 15-year-old could handle is to invite ridicule and contempt.

In short, let there be fewer formulae and more invention, fewer rules and more give-and-take. No filmmaking robot has yet been invented, and heaven help us when it is. Only the living spirit of new ideas can rescue the industry from the dead grip of past conventions: face this one truth, and the way is free for a British new wave to roll in, clean, fresh and salty.

☞

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.