Web exclusive

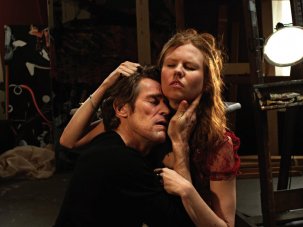

Blue Jasmine (2013)

There’s little doubt in my mind that Blue Jasmine (2013), which I just caught up with on DVD, is one of Woody Allen’s finest achievements. The film stars Cate Blanchett as Jasmine (though her ‘real’ name is Jeanette), a middle-aged woman whose privileged New York lifestyle came to an end when her husband Hal (Alec Baldwin) was exposed as a Bernie Madoff-style fraudster. Now virtually penniless, Jasmine has been forced to take refuge with her sister, Ginger (Sally Hawkins), in San Francisco.

Blue Jasmine is available now on DVD and Video on Demand.

Blue Jasmine is a typical auteur film. Rich as it may seem when viewed in isolation, it looks much richer in the context of its creator’s body of work. Allen often focuses on characters who, like Jeanette/Jasmine, reinvent themselves to blend with their surroundings. The key title here is Zelig (1983), whose eponymous protagonist regularly changes his personality, nationality, shape, and ethnicity.

Jasmine is a strikingly Zelig-like figure, though her situation is far more tragic. If the ‘true’ Zelig could not be revealed while he was imitating those around him, Jasmine will cease to exist if she stops acting (hence her constant monologues, delivered to anyone who will listen, or to herself). Whereas Zelig could fit in anywhere, Jasmine fits in nowhere.

She’s constantly upbraided for getting the details of proletarian existence wrong: she flies first class, turns her nose up at the thought of menial employment and despises Ginger’s working stiff boyfriend. Yet when she returns to her society-hostess persona after meeting the wealthy Dwight Westlake (Peter Sarsgaard), she is accused of having misrepresented herself. Her dilemma recalls that of Chris Wilton (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) in Match Point (2005), who meticulously eliminates all trace of his plebeian roots in order to be accepted by his wife’s aristocratic family.

Blue Jasmine (2013)

But Allen’s studies of genuine and false identities have now arrived at a point where all identity is shown to be false, all worlds theatrical, all relationships performative. Even Jasmine’s connection with her sister is rooted not in biological reality, but rather a form of familial role-playing: they were, it turns out, adopted. The sisters’ past history is notably vague (“Our paths just went in totally different directions”), and since they both appear to have assumed the personalities of their husbands, we are never certain whether it is Jasmine or Ginger who has deviated from her ‘authentic’ background – an ambiguity stressed by the casting of Australian and British actresses who are ‘doing’ American accents.

Blue Jasmine has a great deal in common with Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2008), which began by focusing on two women who were variations on the same dilemma, showed them splitting apart and fragmenting under a series of different influences, then returned them to point zero, effectively unchanged.

Blue Jasmine – which might have been entitled Jasmine Ginger San Francisco – charts a similar trajectory. But here, point zero is itself acknowledged to be illusory, just another in a long line of deceptive surfaces. By wilfully refusing to see that Hal is a calculating criminal, Jasmine even deceives herself, becoming both performer and audience.

Yet Allen is at pains to remind us that, if all gestures are performed, they nonetheless have consequences. When Jasmine insists she regrets calling the FBI, she becomes an actress having second thoughts about a spontaneous improvisation, and asking for another take. But this phone call had a number of concrete effect – Hal was sent to prison, where he committed suicide; Jasmine’s privileged lifestyle came to an end; her son (actually a stepson, another performed familial connection) cut all ties with her, and now claims to have “become a different person” – which cannot be erased by stylish gestures.

Blue Jasmine (2013)

Jasmine’s attempt to construct her identity from moment to moment (“I’m a new person”) is the only possible response to the situation she finds herself in, yet it is doomed to failure. She is as hopelessly ‘split’ as the protagonist of Melinda and Melinda (2004), whose conflicting genre worlds were as real and as fake as Blue Jasmine’s conflicting class worlds, and just as dominated by rules of ‘appropriate’ behaviour. At least the ‘funny’ and ‘serious’ narratives inhabited by Melinda were kept rigorously separate.

Jasmine’s dilemma, on the other hand, is that she can never tell which class she belongs to, just as we cannot tell if the text which presents her to us is comic or dramatic. Several scenes function in both modes simultaneously, making this a film as schizophrenic as its heroine.

Little wonder that Jasmine is confused; that she doesn’t understand why her inner life cannot be reconciled with her biography (“My feelings, my ideas, my humour. Isn’t that who I am?”); that she repeats conversations from her past (a past which seems as immediate as her present) as if she were rehearsing dialogue; and, in a concluding gesture of solidarity between director and character, that she becomes aware of the extra-diegetic music playing on the soundtrack.

All of which is to say that Blue Jasmine embodies a concept of seriousness directly opposed to the superficiality of postmodern culture. Woody Allen has been much under discussion in recent months, not because of this sublime film but rather because the accusations of child abuse that emerged in the wake of his breakup with Mia Farrow have been given a new airing by his adopted daughter Dylan.

What’s so dispiriting about this controversy is the passion it has aroused in people not involved. Whether they’re pro, con or somewhere in between, it seems everyone has an opinion on the subject, and a burning desire to express it. I don’t recall there ever being this much interest in discussing Allen’s actual work. Apparently, the gossip speaks to people in a way the films don’t.

In the April 2011 issue of Sight & Sound

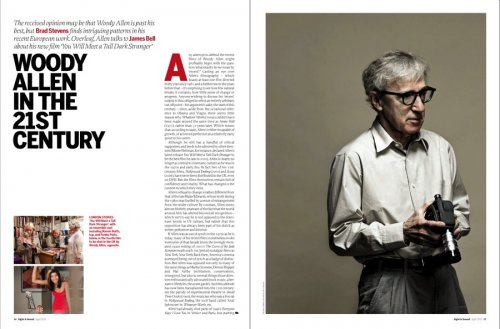

Cover feature: Woody Allen in the 21st century

The received opinion may be that Woody Allen is past his best as a director, but Brad Stevens finds intriguing patterns in his European-set films of the last decade.

+ A good bet

Woody Allen talks to James Bell about filming in London, living in a godless universe – and why he’s pessimistic about everything in life, except his work.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.