Difficult as it is to believe from the vantage point of the Brexit era, England was once among the world’s hippest countries. This was particularly so during the 1960s, when our national cinema was revitalised not only by the appearance of distinctive home-grown talents, but also by the contributions of several foreign-born directors who chose London as a setting.

Yet what did these visiting auteurs hear when they listened to Britain? This question might best be answered by considering three films that have a surprising amount in common: Otto Preminger’s Bunny Lake Is Missing (1965), Roman Polanski’s Repulsion (1965) and Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup (1966).

In the Preminger, an American, Ann Lake (Carol Lynley), learns that her four-year-old daughter Bunny has vanished from a pre-school where nobody can recall seeing her. Questions as to whether Bunny even exists are soon raised, casting doubts on Ann’s sanity.

Carol Lynley as Ann Lake in Bunny Lake Is Missing (1965)

In the Polanski, a young French woman, Carol (Catherine Deneuve), living with her sister in London suffers a mental breakdown when left alone in her flat. Incapable of distinguishing between reality and hallucination, she kills her landlord and her boyfriend.

In the Antonioni, a nameless photographer (David Hemmings) accidentally photographs a murder being committed in a park. Unable to convince anyone of what he saw, and with corpse and photos having vanished, he comes to doubt that the murder ever took place.

The pattern formed by these three distinguished films is strikingly clear, since they all pivot around individuals whose view of the world has become unreliable. And there are traces of this theme in other 60s London films by foreign-born directors, particularly Joe Massot’s Wonderwall (1968) and Jerzy Skolimowski’s Deep End (1970), which might both be described as male versions of Repulsion.

Mia Farrow and Elizabeth Taylor in Secret Ceremony (1968)

Other relevant titles include two by Joseph Losey, who arrived here during the 50s as a refugee from McCarthyism. In The Servant (1964), a wealthy young man finds his certainties concerning the class system (and his own sexuality) undermined by a servant who gradually effects a shift of power; while in Secret Ceremony (1968) a prostitute engages in a series of ritualistic games with a wealthy young woman who casts her in the role of a mother figure.

Francois Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 (1966) takes place in a futuristic England where books are illegal and firemen tasked with burning them, the hero being a fireman who comes to realise everything he has been told about history is untrue. Anthony Mann’s A Dandy in Aspic (1968) has a Russian double agent being assigned by British intelligence to hunt down an assassin who is actually himself, a task requiring him to play multiple contradictory roles.

Robert Aldrich’s The Killing of Sister George (1968) focuses on June Buckridge (Beryl Reid), an actress in a popular soap opera who discovers that her onscreen character, Sister George, is about to be killed off. Despite frequently being addressed as ‘George’ by acquaintances, June knows perfectly well that she is not ‘Sister George’ – indeed, the secret she must conceal from her adoring public is that she is in every way unlike this asexual and saintly character. Yet June nonetheless comes to perceive her onscreen death as tantamount to an actual murder. When her lesbian lover Alice (Susannah York), who treats dolls as if they were human beings (a motif shared with Bunny Lake Is Missing), chides June for talking about the soap opera “as if it was real”, June insists; “It is real to millions of people. Much more real than you or I or any of us.”

The Killing of Sister George (1968)

The sense that fantasy and reality, identity and role-playing have become hopelessly confused unites all these films. Consider what is implied by having Julie Christie play two unconnected parts in Fahrenheit 451; or by the sequence in Sidney Lumet’s The Deadly Affair (1966) which depicts spy games being played inside a theatre as no more (or less) consequential than the production of Edward II taking place onstage; or by the opening of Frank Tashlin’s The Alphabet Murders (1965), in which Tony Randall introduces himself directly to the camera as both Tony Randall and Hercule Poirot before demanding that we stop following him (“This is London! Nothing is going to happen!”), neatly matched by the ending of Jerry Lewis’s One More Time (1969), in which the two stars confess that they are Sammy Davis Jr. and Peter Lawford.

Although such themes are occasionally explored in 60s films by British directors, notably Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s Performance (1970), they seem particularly important to artists seeing London with fresh eyes. But fresh in this context does not mean uncritical. Bunny Lake Is Missing and Blowup both utilise pop groups to raise doubts about the cultural climate: Preminger shows a pub landlord deciding his customers will not be interested in a television report concerning Bunny’s disappearance, and switching to a channel broadcasting a performance by the Zombies; Antonioni shows his photographer entering a club in which the Yardbirds are playing before an audience comprised of young people staring vacantly at the stage. When one of the musicians smashes his guitar, this audience is transformed from mindless passivity to mindless violence, fighting for possession of the ruined instrument.

David Hemmings as the photographer of Blowup (1966)

Although Blowup is considered a key work of the swinging 60s, what catches Antonioni’s eye is not the London of Carnaby Street but rather a city in which signs of modernity are springing up like mushrooms within a landscape that is still recognisably pre-war, a landscape of doss houses, terraced buildings and antique shops. What these directors found was a country in transition from one way of life to another. In a milieu where all certainties – particularly those concerning class, gender and sexuality – were being called into question, it is hardly surprising that definitions of ‘reality’ felt increasingly provisional; Antonioni’s photographer casually invents a series of presumably non-existent familial ties, while the women of Secret Ceremony spin a similar web of relationships via a succession of actorly improvisations. Preminger and Antonioni bracket popular music with a burgeoning callousness, yet their sympathies for individuals navigating these treacherous waters has no truck with conservatism – Carol’s refusal to distinguish between ‘normal’ masculine behaviour and violent threats has obvious feminist connotations, while Ann’s determination not to succumb to ‘gaslighting’ anticipates #MeToo.

Antonioni and Preminger’s association of youth movements with apathy is shared by Lucio Fulci’s Lizard in a Woman’s Skin (1971), a London-based giallo in which a hippie couple look on emotionlessly as a murder takes place. Fulci’s film is another variation on the themes of Blowup, Repulsion and Bunny Lake Is Missing (like the latter, it includes a scene showing the heroine coming across a room full of trapped animals while wandering the corridors of a hospital), and it is here that we encounter a full-blown reactionary view of the period.

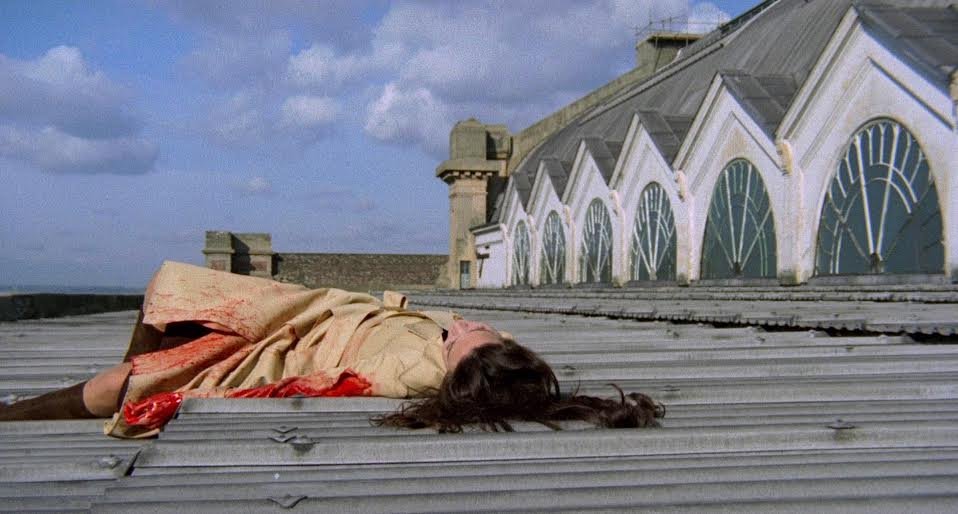

Lizard in a Woman's Skin (1971)

Lizard in a Woman’s Skin’s protagonist, who shares a first name with Repulsion’s, recounts dreams in which she kills her neighbour to a psychiatrist. When the neighbour dies in precisely the manner described in these dreams, Fulci’s Carol (Florinda Bolkan) falls under suspicion of having committed the murder. The film seems to be preparing us for a climax in which Carol, like Ann Lake, is revealed to be the victim of a masculine conspiracy.

On the contrary, it turns out that Carol was herself the manipulator, manufacturing evidence to conceal the fact that she is a killer whose crime was carried out to prevent her lesbian relationship being made public (sounding a crude echo of The Killing of Sister George). Fulci rejects Antonioni, Preminger and Polanski’s emphasis on characters whose views of reality have become unreliable, instead presenting us with a malevolent woman whose assertion of agency involves orchestrating reality to devious ends. All that’s left is for the police to reintroduce traditional authority in the final scene.

The shift from leftist uncertainty to right-wing venom signalled by Lizard in a Woman’s Skin anticipates a similar shift in British society, one which has led to a majority voting to leave the European Union for reasons as passionate as they are vague. Perhaps it was this extremely British disconnect between objective and subjective perceptions of reality that Preminger, Antonioni and Polanski were already picking up on more than 50 years ago, and which a handful of later works by sojourning auteurs – Skolimowski’s Moonlighting (1982), Woody Allen’s Match Point (2006), Nakata Hideo’s Chatroom (2010) – subsequently confirmed. In light of our politicians’ determination to proceed with Brexit despite knowing it will not bring about any of the intended results, the final scene of Blowup provides the perfect metaphor for Britain’s current predicament. Like the photographer played by David Hemmings, we cannot take our eyes off that tennis ball we know full well isn’t actually there.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.