Web exclusive

There was a gap of nine years between Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers and Me and You, due mainly to the fact that the back problems which have long plagued the director eventually meant that he became a wheelchair-user. Having come to accept his diminished mobility, he found a subject – in Niccolò Ammaniti’s novel Io e Te – that suited his purposes: the meeting of teenage boy, hiding out in the basement of the apartment block where he lives with his parents, with the 25-year-old half-sister he barely knew existed.

It’s more or less a two-hander, then, though Bertolucci opens the movie with Lorenzo (Malcolm McDowell-lookalike Jacopo Olmo) reluctantly undergoing a session with a psychiatrist (himself also, as it happens, in a wheelchair). Judging by the boy’s tantrum when he insists his mother let him out of the car at some distance from the bus where his schoolmates are gathered to go on a skiing trip, it’s clear that Lorenzo has his problems – though the real reason he wants to be dropped off away from the kids is that he’s no intention of joining them at all; he’d rather relax in secret in the cellar, alone with his books, music and ants for a week.

All that changes when Olivia – a junkie going into cold turkey – turns up out of the blue, looking for long-lost belongings. Inevitably, sharing both the cramped space and revelations about their father’s familial arrangements makes for conflict… but also, in time, for mutual support and even intimacy. As alert (and largely sympathetic) as ever to the confusions, curiosity, vitality and delusions of youth, Bertolucci makes the most of the pair’s few days together; since Lorenzo had already embarrassed his mother with some transparently Freudian questions, it’s hardly surprising that there’s a sexual element in the siblings’ responses to one another. (Fascinatingly, when we first glimpse Olivia, it’s a little difficult to tell if this hieratically handsome creature is a woman or a transvestite.)

Bertolucci explores the strange, subterranean realm of these enfants terribles with characteristic visual flair: décor, costumes, colour and camera movements combine to create a faintly feverish atmosphere. Interestingly, however, the mise en scène is not especially baroque; though expressive, it’s carefully controlled so that the style suits the parameters of the story.

A modest film, then, but enjoyably so: the two lead turns are spot-on, and the use of a reworded Italian version of ‘Space Oddity’ (but still sung by Bowie) deftly captures not only the dynamics of the pair’s brief encounter but the aching, fragile hopes of a boy in need of a friend.

← Previous: Last works and wakes: Alain Resnais in the underworld

-

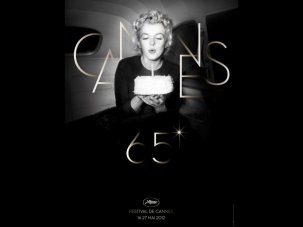

Cannes Film Festival 2012 – all our coverage

See our previews, first-look reviews, festival roundups and awards reactions.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.