Web exclusive

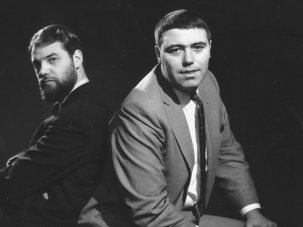

Le Donk & Scor-zay-zee (2009)

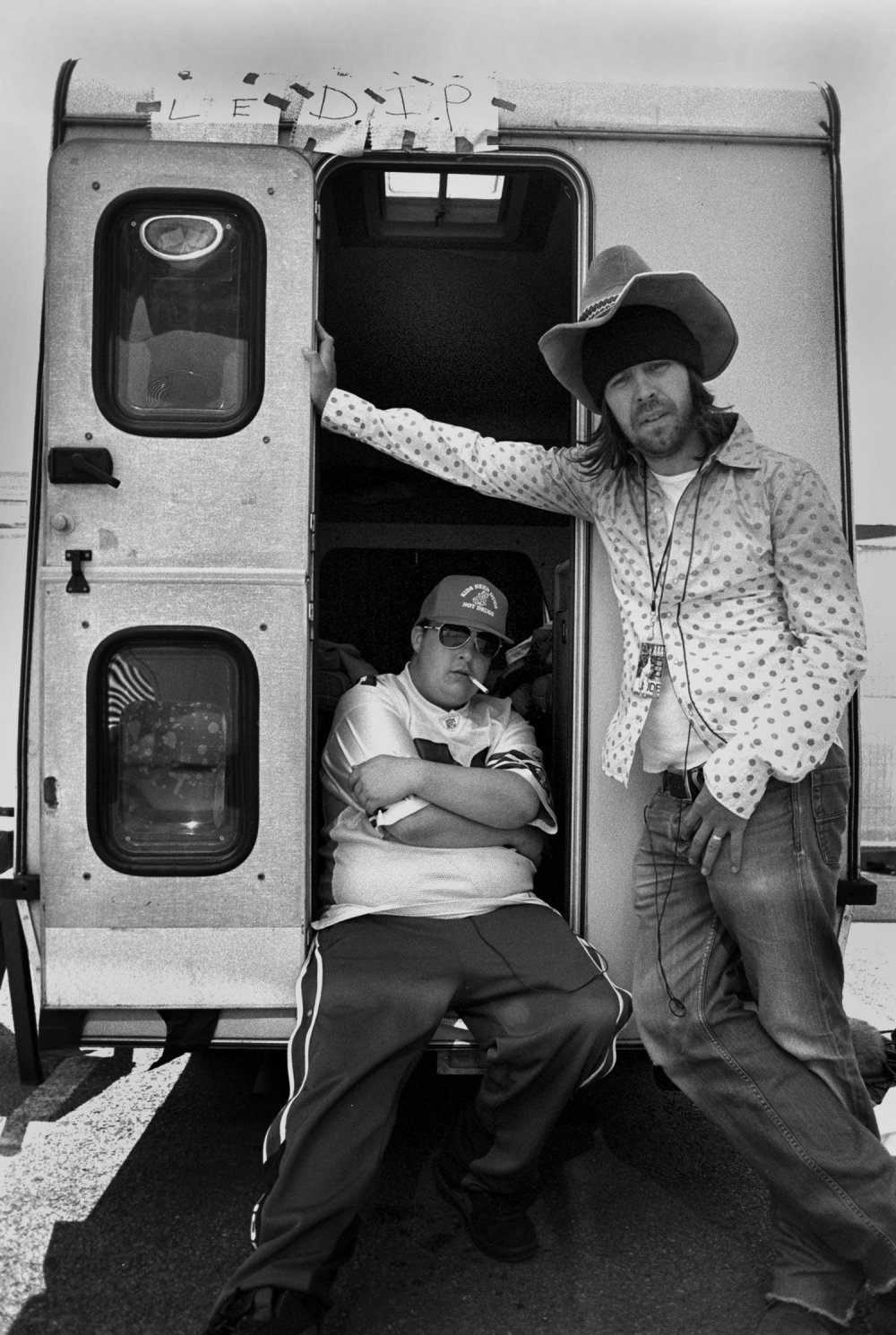

After the small-time suburban tempest of A Room for Romeo Brass and the provincial black-comic-operatic vendetta of Dead Man’s Shoes, Shane Meadows’ latest showcase for the talents of his fellow college dropout Paddy Considine, Le Donk and Scor-Zay-Zee, is their most off-the-cuff yet. Shot live over five days, the film teams one of Considine’s long-time alter-egos – Le Donk, a scabrous, blustering roadie and would-be industry fixer-cum-star – with the real-life Nottingham rapper Scor-Zay-Zee, playing Le Donk’s taciturn lodger.

As he and Scor-Zay-Zee pile up the M1 in an old VW campervan, aiming to blag their way to glory on stage at the Arctic Monkeys’ 2007 gig at the Old Trafford Cricket Ground, Le Donk’s ex-girlfriend (Olivia Colman) is giving birth to their child in the company of a more reliable man. (As Mark Fisher observes in his review in our November 2009 issue, Le Donk has “a stoner temperament coloured by East Midlands mordancy”; he’s a tragicomic figure “more like Tony Hancock than David Brent”.)

Meadows himself became a father in between the film’s five-day shoot and its more leisurely edit. He’s now working on a four-part Channel 4 series follow-up to This is England, and a feature based on Robert Lee’s exorcist memoir Beware the Devil; but as he discusses below, he’s also hoping to parlay Le Donk’s five-day shooting format into a whole new school of ultra-low-budget, no-excuses guerrilla filmmaking.

Where does the film sit in terms of autobiography? Is there a sense that Paddy could have been Le Donk in a different life?

I think it’s more that these are people you come across when you first join a band. Me and Paddy dropped out of art school and started a group [She Talks to Angels] that was like The Beatles without any good songs or any success. These people come up to you at a gig and say “I really like your stuff, I’ve got contacts at EMI and blah blah blah, you should come round to my studio and do some recording,” and you go home that night like “We’ve made it, we’re going to hit the big time.” Then you turn up at their house and it’s a stinky little terrace in the worst part of Burton-on-Trent. And he comes to the door in his underpants, and you think: “Jesus, this is not quite what was on the label.” You get hardened to it, but there’s a lot of people out there, small-town shysters who’ve got no talent themselves, they leach it out of other people and they’ve got no contacts.

So Le Donk is a mishmash of these people, roadies who claimed they’d been touring with the Black Crowes when in fact they’d been touring Walsall with Dumpy’s Rusty Nuts. This was a world we entered into, and as much as the film isn’t a heart-wrenching personal story, it’s still from somewhere quite real that we went through as kids. What am I now, 36? – so it’s 19, 20 years that this character’s been floating around.

Was there a nervousness about hanging a film entirely on Paddy and his improvisation, or were you quite relaxed about where the film was going?

We were improvising as a crew as well! We didn’t meet Scor-Zay-Zee until a couple of days before leaving for the concert. I’d cast a couple of people as lodgers in Le Donk’s house, and Scor-Zay-Zee turned up for an audition for this tiny part. We found out he was this retired real-life rapper and he reeled off a few raps, and I was like, “Paddy, we haven’t actually got a story here, we’re just going to a concert with no story, so maybe we should take him because it’s a music festival and he’s a musician, something might happen…” Paddy’s playing a character, but pretty much nothing else was pre-planned. The Arctic Monkeys only gave us permission to shoot backstage and Scor-Zay-Zee did blag his way on stage and get his keyboard plugged in, so there’s this lovely, liberating mix of fact and fiction.

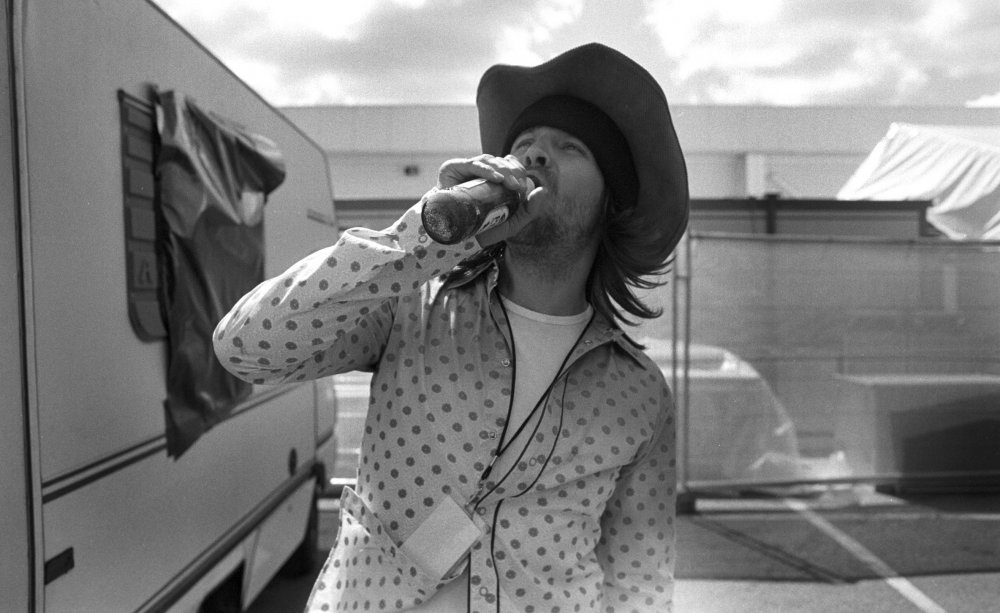

It really comes down to the gods a bit – you have to believe in the character, and I obviously believe in Paddy. I don’t know many other people that have that ability; the Steve Coogans and Sacha Baron-Cohens of this world are great and have a range of characters, but they have a lot of writers that help them to generate that material. Spinal Tap’s genius was probably written down and planned. Paddy generates it in his head on the spot, and that’s quite a different thing. Not many directors would know how to keep a handle on it, and my job as a director is to say I think you should follow this thread. You know, if we can’t get on stage then it’ll be a film about failure, but if we can then maybe it’ll be a bit different, and we’ll have the chance to get 50,000 people in a £50,000 film.

Le Donk & Scor-zay-zee (2009)

How did taking the stage in front of a live crowd affect Paddy? He’s not normally the board-treading actorly type.

It’s one thing going out knowing that the audience are being paid to love it, but when you go out and you’re just about to sing ‘Calm Down Deirdre Barlow’ [an incantatory ditty that Le Donk pulls out of his pocket the night before the gig], you could be in for a really rough ride. There’s a certain noise that 50,000 people make, even when they’re not shouting or screaming – you can just tell that there’s an immense amount of people 50 foot away. Paddy’s notorious for staying in character, especially when we work together. And looking around that backstage curtain and then looking back at him – every other second of that shoot it had been Le Donk looking back at me, but that was the one time it was Paddy. I think he was shitting himself, and it really helped. Whereas Scor-Zay-Zee was really calm.

Warp Films seem like a good outfit to be experimenting with on the film’s release.

This whole thing has been a chance to see everything from the other side. We’re releasing the film ourselves, and we’ve had to be creative. When we took the film to the Edinburgh Film Festival we wanted to hold a party – and we’ve now realised the reason we never make any money off films is because of all the parties the distributors throw for you up front. They take you out for a meal, offer whatever you want, and at the end of the night you say “Thanks so much” – you don’t realise you’ve just paid for it. In Edinburgh we got quoted about 15 grand for a party, and we were like, “Where are the magic rabbits who pay for this stuff?” And Mark [Herbert, the producer] said, “It’s us. And it always would have been us.” So we put it on for 300 quid. And it got party of the week in one of the newspapers.

All the way through we’ve tried to go against the grain a bit, taking inspiration from people like Factory Records who just got in there and did it: take the product yourselves and hand it out on the streets in white sleeves if you have to. Before, you’d get driven around in limos, treated like a king and all of that; but I think seeing how you can get it out there yourself gives you a lot of hope, because if the film industry does collapse – and it’s on its knees, in a way – you know that you’ve got this cottage industry; that Mark, Paddy and I could club together some of our own money and get the film out there ourselves. It’s been a real guinea pig of a project.

And now you’re proposing to become the Svengali of the ‘5 Day Feature’.

The idea came out of the first film I made, Smalltime, which was shot in five days. I don’t know why I put a flag in the ground; I just thought that part of the life-sapping thing about making a film is the amount of time everything takes. This Is England was a beautiful experience, but a really tiring one. After two or three months of filming you can go slowly insane. No-one can go insane in five days – you’d have to have an unbelievably heinous, Apocalypse Now-type experience, with all your equipment breaking down and tornadoes, water torture at night. If you went into a school and said to kids, you’re going to make a feature film, you’re going to be shooting every day for 12 weeks – man, that’s going to be a hard one to pull together. But if you go into even a primary school and try to do something for five days, everything seems possible, it shouldn’t seem out of anyone’s reach. And that’s the beautiful thing: for an established director, it’s a chance to have almost like a week off and get back to their roots, just enjoy themselves, and for someone just starting out it’s not so frightening, I don’t think.

I looked into the whole Dogme manifesto thing, and it was: you’re not allowed to eat a bacon sandwich; you have to smack someone with the tape recorder… It was so restrictive, and it isn’t actually helping anybody. If you want to do one then fine, but I wanted to say the five days is the only limit – that and your imagination. So although we haven’t got a pot of money yet, the dream is that we create this micro studio. Our whole entire budget might be less than half one low-budget film, but we might be able to create ten or 15 features with that. If we can help get some projects off the ground, give them our stamp of approval and say we believe in this person, that would be phenomenal.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.