The Cinémathèque Française’s 2008 restoration of Max Ophuls’ Lola Montès (1955) includes a remarkable moment which, so far as I’m aware, was missing from all previously circulating prints.

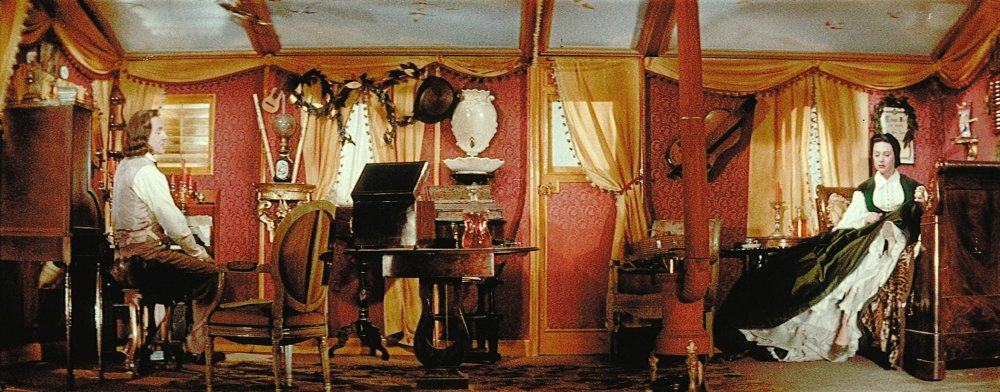

While travelling by coach with Franz Liszt (Will Quadflieg), Lola (Martine Carol) is shown lying on a bed at the extreme right of the screen as Liszt sits composing behind a piano at the extreme left. Suddenly becoming exasperated with her current lover’s artistic efforts, Lola jumps up and crosses the CinemaScope frame, leaving the right of this hitherto meticulously balanced shot vacant as she joins Liszt on the left. After demonstrating the correct speed at which the ‘battement de pied’ should be played (“I cannot stay on my toes that long”), Lola returns to her original position, causing Liszt to observe “Up to now, dancers have danced according to my music and not I to theirs.”

Max Ophuls directing Martine Carol on the set of Lola Montès (1955)

Movement here is linked with power – not only a woman’s power over a male composer, but also feminine power over a masculine auteur. “For me, life is movement,” declares Lola, and her journey across the screen suggests how much freedom she has to disrupt both Liszt’s expectations and Ophuls’ compositions, much as she will disrupt various social and political systems of organisation in the course of the film.

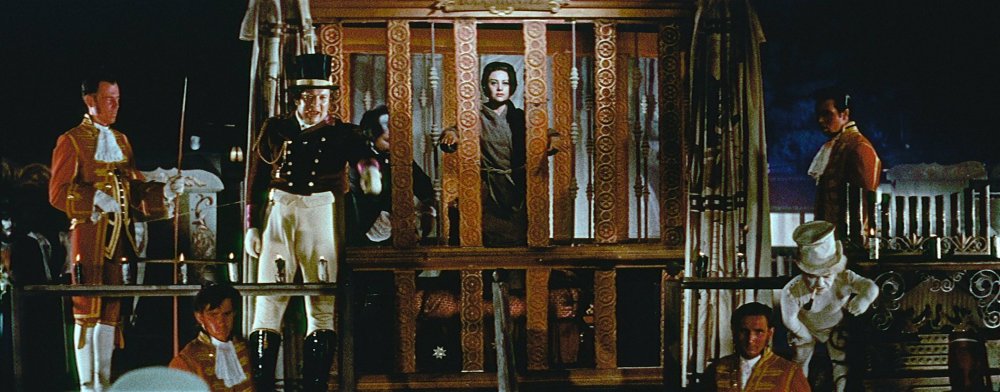

But, as always in Ophuls, freedom is possible only within rigid parameters, and Lola’s liberty is constrained by the very shots which show her in motion – she is free to move, but merely from here to here – as well as the overall narrative, which begins and ends with her on public display in a circus.

The nameless circus master, as played by Peter Ustinov, is both a representative of fate and another helpless victim of those social, romantic and financial structures which entrap Lola.

The relationship between these characters is neatly defined by their first encounter. When the cane-wielding Ustinov visits Lola in her hotel room, she immediately casts him as a spectator of her ‘performance’. Initially, the camera is controlled by Lola, its movements determined by hers as she walks both towards and away from Ustinov, who must meekly follow in order to remain onscreen, and is soon standing awkwardly on the left of an unbalanced frame, the right of which is occupied by a wall.

But as Ustinov begs Lola to “Stop moving about like that,” then, more decisively, commands her to “Stand still,” he raises his cane. With this phallic substitute stretching across the right half of the screen, Ustinov dominates that composition in which he had been helplessly lost a few moments ago.

Lola Montès (1955)

And this proves to be the scene’s turning point. When Ustinov moves again, the camera moves with him, not Lola, as he crosses the room, stopping only when he stops, even following him into an alcove as he explains that he is interested less in talent than in power and efficiency. It is now Ustinov who controls the screen space, assuming the right to define the nature of reality while transforming Lola from active subject to motionless object.

This link between controlling screen space and ‘power’ is often encountered in the work of classical filmmakers, particularly those associated with America’s studio system (through which Ophuls had himself sojourned). Routinely denied the right to choose which projects they undertook, cast the actors they preferred or shape the editing, Hollywood directors knew the only thing they could determine was the mise en scène. Camera movements and compositions were thus associated with control, and even directors who enjoyed greater liberty during pre and postproduction often made this connection.

Vertigo (1958)

Hitchcock is perhaps the supreme example, in that his films frequently focused on characters struggling to dominate cinematic space. We see this most clearly in Vertigo (1958) when Scottie (James Stewart) and Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore) attempt to outmanoeuvre each other during their first meeting, with Elster manipulating Scottie into a chair and standing on a slightly higher level of the room (which, we assume, Hitchcock had his set designer construct on two levels for precisely this purpose).

Similarly, Brandon (John Dall) in Rope (1948) controls both the camera and his reluctant partner-in-crime Philip (Farley Granger) – both are obliged to trail after him as he puts his homicidal scheme into effect – at least until Rupert (Stewart) begins outlining his theory of how the murder took place, and the camera obediently moves around the apartment to reveal precisely those areas he is referring to. Brandon and Rupert are depicted as competing auteurs, and despite the latter’s horrified repudiation of the former’s activities, Hitchcock makes it clear that there is no moral distinction to be made between them; as Philip says, “Cat and mouse. Cat and mouse. But which is the cat and which is the mouse?”

Alfred Hitchcock (to the right of the camera) with crew and cast on the set of Rope (1948)

The reason control of mise en scène became associated with control in a wider sense is not difficult to guess. The enormous sets (usually much larger than their real-life equivalents) typical of Hollywood in the studio era required great effort to construct and decorate. Similarly, cameras of that period were cumbersome, and moving them from point A to point B was a far from straightforward exercise, often requiring many technicians and the laying of tracks. Even the most innocent audiences must have suspected that movies were the result of strenuous labour.

Today, however, we are all masters of mise en scène, capable of manipulating the cinematic texts available to us (which we can pause at will) and creating moving images by simply pressing a few buttons on our mobile phones. It is, then, hardly surprising to find that control of camera movement no longer connotes power in modern cinema, except (in Scorsese, for example) as an ironic commentary on a character’s self-image – which is to say that it stresses the absence or illusion of power rather than its presence or actuality.

Although classical Hollywood provided us with a model of genuinely complex popular art, technological change has distanced us from not merely the immediate social context of these films, but also the assumptions needed to decode their rhetorical gestures. A generation growing up with the ability to ‘make movies’ literally at its fingertips may eventually find this cinematic language almost incomprehensible.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.