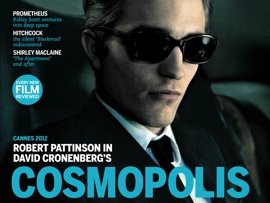

from our July 2012 issue

Doris Dowling and Ray Milland in The Lost Weekend (1945), directed by Billy Wilder

What’s your poison?: Doris Dowling and Ray Milland in The Lost Weekend

Double Indemnity

Billy Wilder; US 1944; Eureka/Masters of Cinema/Region B Blu-ray; 108 minutes; Aspect Ratio 1.37:1; Features: Audio commentary by film historian Nick Redman and screenwriter Lem Dobbs; ‘Shadows of Suspense’ documentary; Screen Guild Theater radio adaptation; theatrical trailer; booklet featuring 1976 interview with Billy Wilder; extract from a 1976 interview with James M. Cain; extract from original screenplay depicting excised ‘death chamber’ ending.

The Lost Weekend

Billy Wilder; US 1945; Eureka/Masters of Cinema/Region B Blu-ray; 101 minutes; Aspect Ratio 1.37:1; Features: video introduction by Alex Cox; three-part 1992 BBC Arena programme ‘Billy, How Did You Do It?’, featuring Volker Schlöndorff in conversation with Billy Wilder; 1946 Screen Guild Theater radio adaptation; original theatrical trailer; booklet featuring essay by David Cairns; vintage public service advertisement by Seagram’s about ‘The Lost Weekend’ and the social dilemma of alcoholism.

Probably even to themselves, Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett made one of the most unlikely collaborative teams in Hollywood – Wilder was the diminutive, Jewish, hard-grafting ex-crime reporter newly arrived in the US having fled Hitler’s Germany; the older Brackett was a member of the American aristocratic intelligentsia: the son of a senator, a metropolitan sophisticate who’d served as a critic for Vanity Fair and the New Yorker. And yet for nearly 15 years following their introduction in 1936, this mismatched pair formed one of the most productive partnerships of the studio era. They were celebrated initially as behind-the-scenes writers, crafting a string of hits for the likes of Ernst Lubitsch (Ninotchka, Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife), Howard Hawks (Ball of Fire), and Mitchell Leisen (Midnight, Arise My Love, Hold Back the Dawn), and then, following Wilder’s 1942 US directorial debut The Major and the Minor, co-written by Brackett, as a formidable filmmaking team in their own right.

Their differences inevitably caused friction, which grew over time, and they would split after winning their fourth shared Oscar for Sunset Blvd. in 1950, but both freely acknowledged that the other pushed them to explore areas they wouldn’t have alone.

However – perhaps in an indication of the differing regard in which ‘pulp’ was held between Europeans and Americans at the time – adapting James M. Cain’s novella Double Indemnity, about an insurance man lured into murder by a manipulative temptress, was a step too far for Brackett, who considered Cain’s writing beneath his talents and left the project after helping to write a treatment. Wilder then went to a fellow emigré living in Los Angeles, Raymond Chandler, who had his own snobberies, and who fought with Wilder throughout, but knew better than anybody the particularly American poetry and profound disquiet embedded in the ‘tawdry’ crime story.

Fred Macmurray and Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity (1944), directed by Billy Wilder

Anatomy of a murder: Fred MacMurray and Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity

Double Indemnity, of course, needs no introduction as the cornerstone of film noir, but Masters of Cinema’s new Blu-ray does it proud, capturing John F. Seitz’s cinematography in its full glory; the dusty air of Phyllis Dietrichson’s Spanish-style villa shimmering sharply in the bars of light cast by the Venetian blinds. What would become well-worn tropes in countless imitators are found here in irreducible freshness. Fred MacMurray was never much of an actor, but such was the luck or inspiration of the casting that his earnest schmuck is the perfect foil for Barbara Stanwyck’s Phyllis – all other femmes fatales trail in her wake. Though always striking, not least in her outrageous blonde wig, the fact that Stanwyck was never one of the great screen beauties only adds to her character’s sense of ruthlessness – she has to work to ensnare her prey. Any greater beauty would be out of MacMurray’s league, just as any more assured man would be beyond hers.

Brackett returned for Wilder’s next film, an adaptation of Charles Jackson’s novel The Lost Weekend, about an alcoholic writer who recognises that he’s drowning his talents, but is powerless to address his problem. Wilder read the book and felt it could make an important picture – “the first film with an alcoholic who isn’t a comedian.” As David Cairns notes in the booklet accompanying Masters of Cinema’s Blu-ray, that’s not strictly true, but the film did much to shift the engrained idea that alcoholism was the result of a character flaw and not a sickness – that alcoholics could be seen as sufferers and not merely losers.

That it succeeds in imparting that perception is due in no small part to Ray Milland’s performance as Don Birnam, the alcoholic at the centre of the film. Milland had felt anxious about taking on the role, and had to be talked into it by Wilder, but he delivers the performance of his career, as was acknowledged when he won the Oscar for best actor in 1946.

Perhaps the most celebrated sequence in the film is one following Milland as he trawls downtown New York city streets desperately looking for a pawn shop to flog his typewriter so he can buy drink. Wilder, working again with Seitz, had cameramen hidden in boxes along 3rd Avenue as Milland, in character, stumbled through the unsuspecting public.

It’s a stretch to call such scenes, as some have done, an equivalent to Italian neo-realism, but the use of real locations showing the unseen, grimy New York, as well as the frighteningly expressive, almost Wellesian passages portraying Birnam’s nightmarish drink-induced hallucinations, was shocking for the time, and almost prompted Paramount to shelve the film. They relented, but Wilder and Brackett felt duty-bound to tack on a wholly unconvincing happy ending.

The many extras include Billy, How Did You Do It?, a fascinating, exhaustive five-hour-long series of interviews with Wilder by Volker Schlöndorff. Wilder was in his eighties at the time of filming, but his infectious energy is entirely undimmed; he swivels constantly in his chair, his hands animated throughout as he reminisces about his life and work.