Web exclusive

Wild Grass (Les Herbes folles, 2008)

“Right on the edge of the film, there’s another system: an array of heterogeneous objects, from flowers to sewing-machines. They’re mysterious, Surrealist, almost alive. They need the brain to make sense of them. And that’s where we live. The links which make life meaningful are the cracks between the facts.”

— Raymond Durgnat on Mon Oncle d’Amérique

It starts like a Brian De Palma movie, in a mode of full exhilaration. Shots of feet take us to a chic shopping centre. A voice-over informs us that a woman – Marguerite (Sabine Azéma), whose face will not be fully seen from the front until six and half minutes into the film – has special shoe requirements, and this specialness is what will kick off ‘the incident’ (the title of Christian Gailly’s novel) at the heart of the narrative.

Jonathan Romney’s analysis of Wild Grass and interview with Alain Resnais, and Tony Rayns’ review of the film, are published in the July 2010 issue of Sight and Sound.

Point-of-view rules, but on a split register: both the character’s sensorial experience of her surroundings, and the camera’s insistent display of its own, peculiar way of seeing things. Sudden bursts of slow-motion linger on the saleswoman who thrills Marguerite (it is her secret), and eventually on the roller-blading thief who snatches her purse. Mark Snow’s musical score soars. Within the shoe shop itself, we could almost be watching a scene from Sex and the City: a rapid but luxuriant montage surveys shelves, brands, boxes.

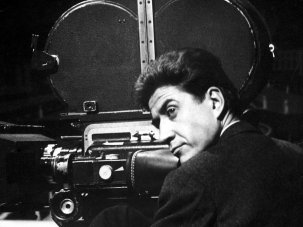

Straight away, Alain Resnais’ masterful new film announces its proudly mixed-up character. Resnais is a director who has always complicated drama with comedy, realism with surrealism, philosophy with pop culture – and vice versa. Invention and surprise are his watchwords: as the French critic François Thomas once remarked, Resnais’ gambit as an artist is to outrage or confound viewers at the start of a film, but hold them in their seats to the very end. Wild Grass is a relatively gentle work when placed beside Hiroshima, mon amour (1959) or Providence (1976), but it still has the pundits guessing: what is this brazenly youthful film from a man of 87 – deadly serious, or an extended joke? A summing-up of the œuvre, or a taking-off into unknown skies? It manages, magisterially, to be all of these things at once.

The fact is that, although Resnais is undoubtedly an auteur, he has never sought to guide his career in any overarching, thematic way. Projects were posed to him by producers, he claims; people (writers, actors, composers, designers) happened to be available to collaborate with him. However, a certain adherence to ‘automatic writing’ in the Surrealist sense – giving himself over to whatever script was before him, following his intuitions and impulses – has led Resnais, despite himself (which is exactly the way he wants it), to construct a body of work of astounding coherence, a garden of many paths that always lead to the same emotions and concerns.

Wild Grass (Les Herbes folles, 2008)

Thus, as in so many Resnais films, the inciting incident of purse snatching in Wild Grass leads to a strange kind of seemingly-destined encounter: the luck (good or bad, we must decide) of Georges (André Dussolier) in finding Marguerite’s discarded accessory leads quickly to his full-blown obsession, even stalking, of her. Phone calls are made and messages left, letters are sent, cops are called in to issue stern warnings to Georges.

It’s not Fatal Attraction – although Resnais, dancing deftly between genres, leads us to expect this for a while, especially given the dark, never-clarified hints about Georges’ criminal past – but nor is it standard French arthouse fare glorifying amour fou. For, at some almost indiscernible point, something twists in this plot, and Marguerite finds herself interested in, maybe even smitten by Georges – while he begins to dart off on other tracks, including a mind-boggling flirtation with Marguerite’s best friend Josepha (Emmanuelle Devos) in the front seat of her car.

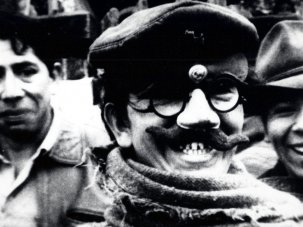

Resnais juggles so many elements in this film. Flashes of the associative editing he mastered long ago rub up against jolly, nostalgic evocations of a pilot’s life – here, Resnais finds in the material at hand an unexpected opportunity to pay homage to the wartime experiences of his old friend, Chris Marker. A riot of artifice in the colour, lighting and décor schemes – “I really like it when a film looks like a film”, he humbly declared in a recent interview – is tempered by shrewd observation of a very real, social mise en scène, a comedy of manners grounded in the everyday: look at all the marvellous scenes involving Mathieu Amalric as a cop, with their protocols of ‘personal space’ and authority subtly challenged, breached or reinforced at every step.

Even before the opening incident of Wild Grass, images under the credits show us tufts of grass that have appeared between the cracks in a pavement, and the film will return often to this motif in many forms. Is this a signal of unconscious dreams, of the return of the repressed? Yes and no. Because, thanks to Gailly’s novel, Resnais is able to tune into something at once more fantastical and more mundane than the familiar Freudian realm. Resnais credits his producer Jean-Louis Livi with the fine formulation that Wild Grass is less about raw desire than something far trickier and more quizzical: a “desire to desire”.

Wild Grass (Les Herbes folles, 2008)

The film captures and enacts – deeply true, on this level, to Gailly’s prose – that odd, inner voice within all the characters that oscillates between conscious, unconscious and preconscious impulses: there is desire, yes, but also the rationalisation, the ‘talking up’ of this desire, the whimsical playing with one’s own desire (and its consequences) as a cat plays with a mouse. And, as in Mon Oncle d’Amérique, it is cinema itself which, as Resnais constantly underlines, both feeds the fantasies and provides the often unliveable ego-ideals. It is all so glorious, and all so frustrating.

Even though Wild Grass is about nothing less than life, love and death, it is not a grandly existential statement; far from it. Exploring the merry maze of what Durgnat called “the cracks between the facts”, Resnais fully finds here what he has sought since at least Life is a Bed of Roses in 1983: an unbearable lightness of being.