Vertigo (Paramount) finds Hitchcock toying weightily with a thriller by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, authors of Les Diaboliques. As with their earlier novel, the mystery is a question not of who done it but of whether it was really done at all – in this case, how can a girl who has fallen spectacularly to her death from a church tower reappear a few months later in the streets of San Francisco, and is she in fact the same girl?

USA 1958

Certificate PG 122 mins approx

Director Alfred Hitchcock

Cast

John ‘Scottie’ Ferguson James Stewart

Judy Barton/Madeleine Elster Kim Novak

Midge Wood Barbara Bel Geddes

Gavin Elster Tom Helmore

[1.50 : 1]

Original UK release date 7 August 1958

UK 60th anniversary re-release date 13 July 2018

Distributor Park Circus

parkcircus.com/film/114360-Vertigo

► Trailer

This question of identity, central to the novel, is disposed of by Hitchcock in a brisk and curiously timed flashback, leaving only the secondary problem of how the hero, a detective who first trails the girl, then becomes obsessed by his memories of her, will react to discovering the truth. But in a story of this kind, a sleight-of-hand affair built on deception and misdirection, mystification counts for everything; to introduce questions of motivation, to suggest that the people involved in this murder game are real, is to risk cracking a plot structure of egg-shell thinness. Only speed, finally, could sustain the illusion that the plot hangs together – and Hitchcock has never made a thriller more stately and deliberate in technique.

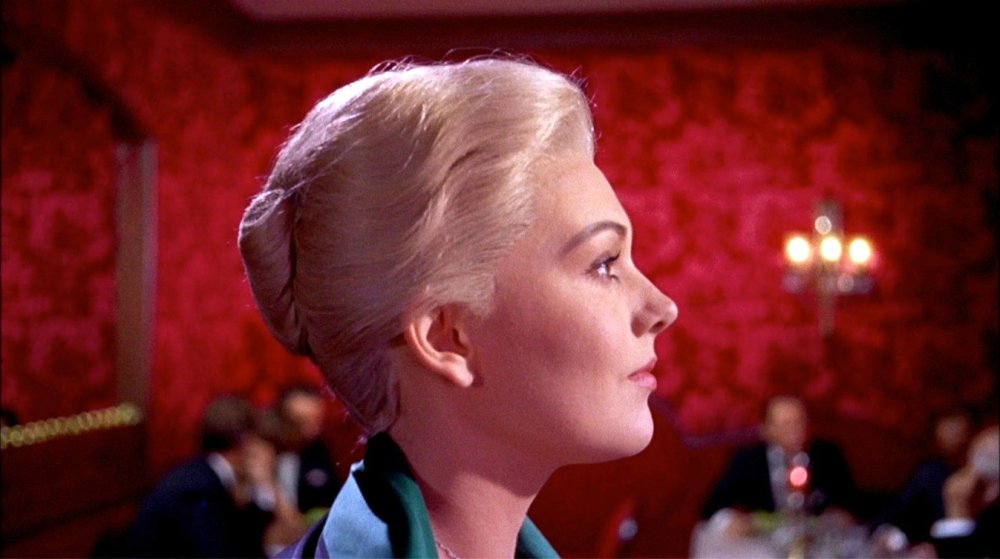

Novak with James Stewart as ‘Scottie’ Ferguson

If the plot fails to work, there are still some good suspense diversions. These include a macabre, misogynistic sequence in which the obsessed detective (James Stewart) enlists dressmakers and hairdressers to make over the lightly disguised Kim Novak number two in the image of the lost Kim Novak number one; a typical Hitchcock joke, in which the detective tracks the girl down an alley, through a dark and dingy passage-way, and finds that this sinister approach is the back door to an expensive flower shop; and a single shot of stunning virtuosity, with a corpse spread eagled across a church roof at one side of the screen, and the detective slinking out of the church door at the screen’s opposite edge. A rooftop chase, decisively opening the picture, a struggle in the church belfry, some backchat in the manner of Rear Window with a cool, astringent second-string heroine (Barbara Bel Geddes) are all reminiscent of things Hitchcock has done before, and generally done with more verve. One is agreeably used to Hitchcock repeating his effects, but this time he is repeating himself in slow-motion.

☞

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.