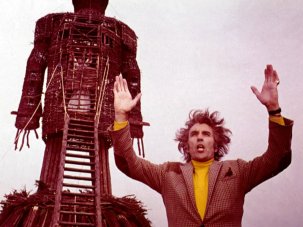

Ari Aster’s debut Hereditary (2018) was a clever ghost story of great freshness and menace. His follow-up is just as charnel but less obviously commercial, and without the attics or ghosts – it’s a daft, hallucinogenic, Ikea folk-horror along the lines of The Wicker Man (1973), as rich, polished and worked as that famous ancient vessel the Gundestrup cauldron. Midsommar has no overt supernatural elements, no sense of gods or eerie forces, and everything is explicable in terms of human belief, hallucination and perhaps folly – with a powerful dose of ritual psychotropic plants. This haunt is herbal. It is a tisane of terror.

USA 2019

Certificate 18 140 mins approx

Director Ari Aster

Cast

Dani Florence Pugh

Christian Jack Reynor

Josh William Jackson Harper

Pelle Vilhelm Blomgren

Mark Will Poulter

Connie Ellora Torchia

Simon Archie Madekwe

[2.00:1]

UK release date 5 July 2019

Distributor Entertainment Film Distributors

midsommar.co.uk

► Trailer

So that’s the first thing: the incontrovertibly supernatural is absent. But there is instead a lurking, a supernatural imminence that flickers around the edges of the action, as if something ghostly might manifest at any point during the movie’s 140-minute running time.

Though the story takes place mostly in Sweden (and was filmed in Hungary, to avoid shooting being restricted to eight hours a day) during the 24-hour sun of the subarctic summer, it begins in a brutally frozen world of snowed-under America, as Dani (a commanding Florence Pugh) desperately tries to contact her parents. The phone rings by their bedside, but they are already dead.

In horror and shock from the tragedy that develops from this point, Dani clings ever more closely to her boyfriend Christian (Jack Reynor), an unreliable meaty oaf who before the crisis was on the brink of ending their relationship. When he unwisely decides to travel to Sweden with some friends to witness a little-known pagan festival in an obscure village inhabited by the Aryan Hårga people, Dani tags along. No one wants her, but she comes anyway. The catalyst for the trip is that one of the friends is writing a postgrad thesis on this strange anthropological scenario – and in a nice touch, he is played by African-American actor William Jackson Harper.

Jack Reynor as Christian (centre) with Pugh

On their arrival, the visitors are warmly welcomed by the white-clothed members of what can only be called a commune, and are immediately given psychotropic herbal drinks and feisty dry compounds to ingest. In all that howling sunshine, the resulting visions are intimations of things to come.

Yet the location is ostensibly without threat – beautiful and open, its woods, cliffs and meadows strewn with flowers, and the few timber buildings exquisitely fashioned and painted with Scandinavian motifs and runes. But what develops, as Dani is crowned May Queen after a bout of dancing that brings to mind stories of medieval ergotism (the hallucinations and feverish impulses that were brought on by eating crops infected with the ergot fungus), is a cornucopia of blood sacrifice and sex magic.

It’s a story that poses a formidable challenge for any cinematographer, since it takes place in constant sunlight, a scenario already used to gothic effect by Christopher Nolan in Insomnia (2002). Here, Pawel Pogorzelski returns following his excellent work on Hereditary: there is overexposure in the place of shadows, pale translucence instead of darkness. The whole idea of inversion, day for night, widdershins and backwards, recurs throughout Midsommar.

The art direction is exceptionally good – the input of designer Henrik Svensson was, by all accounts, key to every stage of the film’s development. The floral horrors are summoned by a camera that is often roving, and are best when they are merely unnerving rather than exploring the material of butchery. The music is cleverly calibrated, from the chilled dissonance of the beginning scenes to the Wagnerian-style pomp of the ending. The insights into European folkloric traditions have a weight of substantial research that is very welcome, but the introduction of fratboy comedy touches doesn’t quite work, the squabbles and vulgarities of these straight male postgrad students shifting Midsommar from a great film to just a very good one.

Early on, the camera lingers on small sources of light, mirrors and reflections, hinting at the whole occult rigmarole of ‘as above, so below’. Sometimes it is trees mirrored in a lake; sometimes the roots of a tree, or a road that becomes the sky when the visitors enter this counter-world of everlasting summer. But the film’s final shot is a moment of complete, jet-black gothic darkness in the blinding, solarised land.

In the August 2019 issue of Sight & Sound

Demons by daylight

Inspired by Midsommar, Kim Newman explores a run of horror films, from The Birds to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, in which the terror moves out of the darkness and into the light.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.