If you’re familiar with Robert Greene’s films or his writings on cinema (he’s a regular contributor to Sight & Sound) then you know he works in anything but absolutes. In fact, over the last half-decade Greene has consistently utilised the medium as a means to locate a more elusive, intermediate state of filmic documentation, one predicated more on inquiry, analysis and reflexivity than strict verisimilitude, often arriving, paradoxically, at something more honest in the process.

USA 2016

110 mins

Director Robert Greene

His latest, Kate Plays Christine, takes this prismatic approach to nonfiction storytelling further than ever before, and was duly awarded the U.S. Documentary Writing Award at Sundance. Not simply an acknowledgment of the film’s self-evident creativity, the award is more so instructive of Greene’s restless, inquisitive approach to the nonfiction form. His films function as much as exercises in dramatic (de)construction – and, indeed, writing – as they do intrepid excursions into social and historical margins.

There are a multitude of subjects explored in Kate Plays Christine. First and foremost are its namesake female subjects: Kate, being the actress Kate Lyn Sheil, and Christine, the real-life television journalist Christine Chubbuck, who committed suicide on a live news broadcast in 1974. On a very elemental level, Greene’s film is a study of how an actor prepares for a role. Fascinated by the performative as well as the psychological dimensions of this fatal display, Greene and Sheil traveled to Sarasota, Florida, to the scene of Chubbuck’s death, to learn about her life and to make a film in which the actress would attempt to portray a woman whose motivations and mindset remain all but irretrievable from the tides of time (even an infamous videotape of the incident is said to be under lock and key).

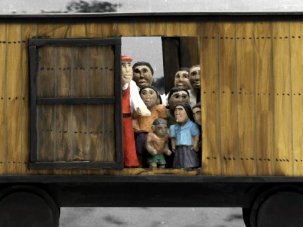

Greene, like many key nonfiction filmmakers before him (Claude Lanzmann, Hara Kazuo, Rithy Panh etc), is interested in reconstructing an historical record of events which have no visual correlative. Here, in the absence of tangible documentation, Greene has enlisted Sheil as both a physical representation of Chubbuck and a cinematic cipher for the reimagining of her psychology.

Needless to say, lines begin to blur between subject and performer, as well as between the film’s various narrative modes. Much of the film follows Sheil as she researches and prepares for her role, which she does cosmetically by spray-tanning and fitting herself for wigs and coloured contact lenses, and analytically when reading aloud from a summary (a script?) of Chubbuck’s actions and absorbing the first-hand recollections of a handful of her subjects’s friends and colleagues. She even retraces bits of Chubbuck’s own footsteps by visiting the television station where the gruesome incident transpired, and later inquiring about a revolver at the very same gun shop where Chubbuck bought hers decades prior.

In between these sequences are reenactments of Chubbuck’s life and the events leading up to her suicide, scenes of speculative drama which Greene and cinematographer Sean Price Williams purposefully stage with an artificiality bordering on the sterile. The austere texture of these episodes, which play something like Fassbinder by way of Sirk, though with little of their grace or elegance, hint at the moral complications and absolution of accountability which Greene believes muddies even the most sincere depictions of the trauma and tragedy which beset Chubbuck and so many like her. As Sheil immerses herself in the role, her own misgivings about the responsibility of her performance likewise begin to take a noticeable toll, though it’s never quite clear – save for in the closing moments, in which Greene simultaneously confronts and subverts the film’s inevitable climax – if what we’re witnessing is Kate playing Christine, or Kate playing Kate playing Christine, or simply Kate herself.

By burrowing past the more sensational aspects of Chubbuck’s story to the more troubling nuances of her psyche (and how those same feelings can manifest in any one of us), Greene and Sheil have a fashioned a more holistic and sympathetic portrait of Chubbuck than any straight fiction could ever hope to.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.