The first part of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s film-autobiography (La Danza de la Realidad, 2013) took a couple of years to get British distribution, but this crowd-funded sequel arrives here less than a year after its Cannes premiere, perhaps because it’s sexier and more flamboyant.

France/Chile 2016

Certificate 15 128 mins approx

Director Alejandro Jodorowsky

Cast

Alejandro Adan Jodorowsky

Sara/Stella Diaz Pamela Flores

Jaime Brontis Jodorowsky

Enrique Lihn Leandro Taub

Alejandro as a boy Jeremias Herkovits

old Alejandro Alejandro Jodorowsky

Maria Lefevre Carolyn Carson

Andres Racz Adonis

Pequeñita, little girl Julia Avendaño

General Carlos Ibáñez del Campo Bastián Bodenhöfer

[1.85:1]

Subtitles

French/Chilean theatrical title Poesía sin fin

UK release date 6 January 2017

Distributor Curzon Artificial Eye

endlesspoetryfilm.com

► Trailer

Endless Poetry is essentially ‘the Santiago years’: it opens with the Jodorowsky family arriving in the city by boat from their former small-town home and closes with the young adult Alejandro leaving for Paris, again by boat. Set mostly in the 1940s and 50s, the action spans young Alejandro’s break with his harsh father Jaime and their eventual reconciliation on the eve of his departure; in between Alejandro grows up, mingles with Santiago’s bohemian artist circle, dabbles in puppet-theatre and circus clowning and comes to embrace his destiny as an anti-fascist poet. The real-life, elderly Jodorowsky – now looking much more dapper and better groomed than he did before his long lay-off from directing – pops up every so often to reassure his younger self (played by his son Adan) that he’s on the right path.

As anarcho-surrealist life stories go this is pretty soft-centred; the auteur has certainly moved on from the time when he was happy to align himself with Arrabal’s theatre of cruelty. Although theism and organised religion took some stick in earlier Jodorowsky movies, bourgeois piety barely gets a mention here and there are none of the scorpion stings found in Buñuel’s best work.

But then Buñuel lived with his Jesuit upbringing all his life, and 2016’s Jodorowsky has only the tarot deck to anchor his poetry. We know from his earlier-life cult hits El Topo (1970) and The Holy Mountain (1973) that Jodorowsky has always had a strong mystical bent, so it probably shouldn’t be a surprise to find him born again as a new-ager. Still, the sheer sappiness of much of the action and the reluctance to linger on episodes of pain and loss are, to say the least, unexpected. Explanation is found in an uncredited press-kit interview with Jodorowsky: “I describe my films as ‘psychomagic’… To me, an art that does not serve a healing purpose is not art… who is it out to heal? Mainly myself. Secondly, my family. And only in third place, a hypothetical audience.”

Someone with first-hand knowledge of Santiago’s boho set in the 1940s might take issue with some of the caricatures and episodes in the film, but the only old score that Jodorowsky is clearly trying to settle is with the poet Nicanor Parra, introduced as young Alejandro’s culture-hero (he makes a puppet of him as a tribute) but later denounced for selling out to academia: he’s shown recommending Alejandro to get a degree and a cushy teaching job with a steady income.

Fortunately the young Alejandro is far too busy living in colour in a black-and-white world for such square advice to cramp his style. The streets of Santiago are filled with crowds in identical masks staring blankly at such incidents as the beating-up of a shoplifter, the notionally hip Café Iris is frequented by somnolent deadbeats in grey suits, but our poet-in-the-making takes up with a succession of inspirational chums who (usually by negative example) guide his progress.

Foremost among them at the outset is the capricious show-off Stella Diaz (played in a crimson wig by Pamela Flores who also – you’ll never guess – plays young Alejandro’s singing mother), who promises the young man non-penetrative sex and provides him with undreamed-of Orphic ecstasies. But then she gives her virginity to an offscreen mystic and disappears from Alejandro’s life and the film, setting a pattern that subsequent chums will follow. The word to define this narrative is ‘episodic’.

The one surprise here is the almost complete absence of heterosexual fulfilment, although there’s heavy emphasis on young Alejandro’s relief at the discovery that he’s not gay. (The fear dawned when his inevitably homophobic dad called him ‘Maricón!’ for reading Lorca.) He later affirms his heterosexuality by nude crowdsurfing across a circus audience, an event which also serves to establish his shift from clownish adolescence to anti-fascist maturity.

Most of the film is as shallow and silly as it sounds, but it’s rarely boring and it generally looks quite vibrant; it’s Chris Doyle’s most prestigious cinematography gig since the break with Wong Kar Wai, and he rises to the occasion with brash, carnivalesque images. The visual effects have an agreeably non-industrial magic to them, particularly in the unfurling of huge old photographs over tacky shopfronts to represent a street’s former magnificence.

—

Correction (6 January 2017): this review (like the version printed in our January 2017 issue) originally claimed that La Danza de la Realidad, the first part of Jodorowsky’s film autobiography, was never released in the UK. In fact Curzon Artificial Eye released it on 21 August 2015. The sentence has now been amended.

-

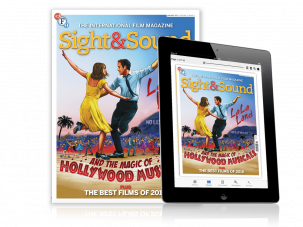

Sight & Sound: the January 2017 issue

Damien Chazelle’s modern musical La La Land, and a new look at exemplary toe-tapper Gene Kelly. Plus Krzysztof Kieslowski, Issa Rae, Eugène...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.