Given that Joel Coen’s previous claim to fame is as an assistant editor on The Evil Dead, it is perhaps appropriate that his directorial debut should be marked by such a strong sense of construction. Here, however, this is not a matter of pacing and rhythm – indeed, the only real criticism one would have is that the film flags somewhat before reaching its wonderful climax – but of plotting. Everything is sacrificed to the machinations of a plot which progresses only by ensuring that none of its characters ever comprehends the web into which they are being spun. The deception worked by Visser on Marty – the doctored photograph showing the ‘dead’ lovers – is an unobtrusive metaphor for the film’s central strategy, whereby each character’s constant misreading of appearances guarantees the fulfilment of a larger scheme of things.

USA 1983

Certificate 15 96 mins (original cut 98m 42s)

Director Joel Coen

Cast

Ray John Getz

Abby Frances McDormand

Julian Marty Dan Hedaya

Visser, private detective M. Emmet Walsh

Director’s cut release date 6 October 2017

Distributor StudioCanal UK/ICO

independentcinemaoffice.org.uk/films/bloodsimple

► Trailer

And this is both refreshing and significant given that outside the specifics of this narrative arrangement, Blood Simple might be following in the path of any voguish film noir – or more specifically, James M. Cain – update: adultery, abundant neon, murder, villainous detective, etc. But by avoiding the trap of making the relationship between Abby and Ray the centre of interest – as one would expect – the film prevents the nightmarish situation from turning into a simple, misogynistic expression of Ray’s anxieties, provoked by his encounter with an 80s femme fatale. Instead, the plot becomes an abstracted, stylised expression of nothing in particular outside itself.

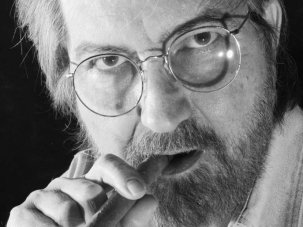

Frances McDormand as Abby

If anything, it is perhaps a matter of geography. An opening voiceover narrows things down from “a world” where “something can always go wrong” to Texas, where “you’re on your own”. Visser opposes the Lone Star state to Russia, where people look out for each other but make only “50 cents a day”; in Texas, he can make $10,000 for the double killing.

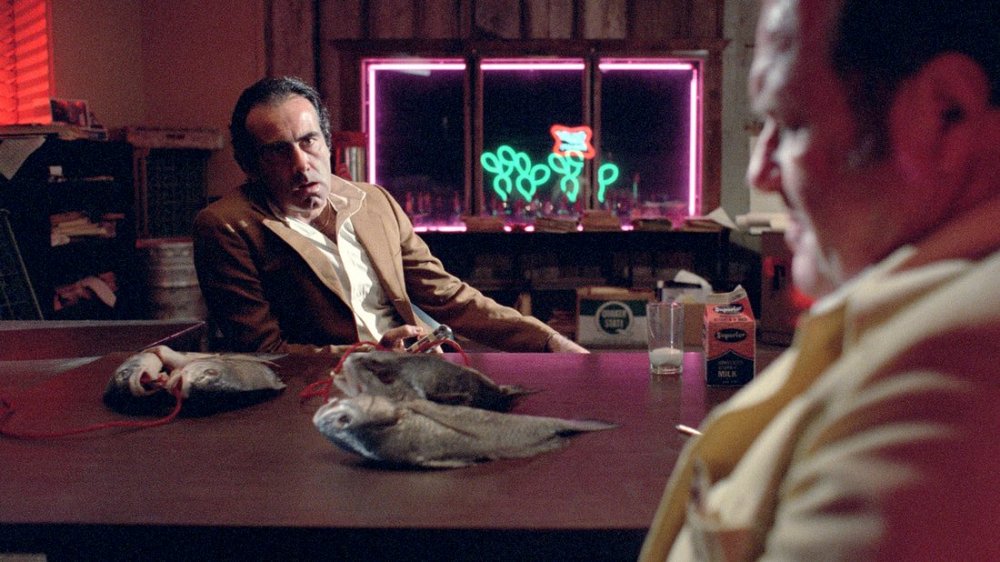

But since the film is devoted to exposing the fatal flaw in this crude opposition – by making arbitrary the relationship between individuals and their actions – it is fitting that Visser should provide the most graphic demonstration of the message. In the final, perfectly judged scene, he finds himself punching his way through a wall with one hand in order to withdraw the knife which has impaled the other on a window sill. The excruciating humour of the contrivance emphasises the peculiar appropriateness of the image – something to do with the left hand not knowing what the right is doing, and the consequences this has for the characters’ interlocked but resolutely separate destinies. Here one might also mention the cigarette lighter which Visser leaves by mistake at the scene of his crime. It is subsequently heavily emphasised, but proves to be the major ‘red herring’ as far as the plot goes. Hence, perhaps, the two dead fish, caught by Marty, which stand guard over the useless clue.

Dan Hedaya as Julian Marty and M. Emmet Walsh as Visser

This kind of imagery is symptomatic of Blood Simple’s strikingly detached sense of style. Coen mobilises his camera around the characters, rather than on their behalf, creating a fatalistic sense of space in which they are all trapped, and in which objects – rather like Marty’s ‘corpse’ – refuse to lie down, taking on a life and significance of their own. Again, this is sometimes arbitrary – a newspaper flying through the air – and sometimes only loosely connected to the plot – the burning garbage which Marty retrospectively fits into his murder plan, as a way of disposing of the bodies.

But the formalism never strays into ‘artiness’, since it reinforces the film’s overall design which, it should be stressed, always maintains its humorous edge. In this respect, one slight regret is that there isn’t room for more to be made of M. Emmet Walsh’s marvellous performance as Visser, an object lesson in villainous seediness. Overall, however, Blood Simple is certainly a strikingly assured first feature.

☞

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.