Spoiler alert: this review reveals a plot twist

Brazil’s most exportable films tend to be those that depict working-class or poverty-level life – prominent successes include City of God (2002), Elite Squad (2007) and, most recently, Gabriel Mascaro’s Neon Bull (2015), about rural rodeo workers. A notable exception was Kleber Mendonça Filho’s Neighbouring Sounds (2012), an ensemble drama featuring characters of different social and racial origins, but set in the predominantly middle- or upper-class milieu of Boa Viagem, a beachfront district of Recife in the north-eastern state of Pernambuco. With its multiple plotlines and allusions to Brazil’s troubled past, Neighbouring Sounds was a panorama film, its dense sound design conveying a sense of how different lives, stories and social spaces pervade each other by way of sonic leakage, either benign (music, the sound of the sea) or invasive (barking guard dogs).

Brazil/France 2016

Certificate 18 146m 7s

Director Kleber Mendonça Filho

Cast

Clara Sonia Braga

Ana Paula Maeve Jinkings

Roberval Irandhir Santos

Diego Humberto Carrão

Ladjane Zoraide Coleto

Cleide Carla Ribas

Seu Geraldo Bonfim Fernando Teixeira

[2.35:1]

Subtitles

UK release date 24 March 2017

Distributor Arrow Films

► Trailer

Mendonça Filho’s follow-up Aquarius is in many ways more conventional; it lacks the exuberant shifting from locale to locale, while toning down the stylistic effects (abrupt zooms, fragmented editing) that gave Neighbouring Sounds a distinctly modernist edge. It essentially tells a single linear story and focuses on one character, Clara, a well-off widow in her sixties; yet this simple conception allows the director to include much incidental and background material that puts Clara’s personal drama in a wider context.

For example, the brief prelude, set a quarter of a century before the main action, doesn’t serve – as one might have expected, given the mass of faces on screen – to introduce the film’s characters. Each face we see merely notifies us that everyone at a party to celebrate Aunt Lucia’s 70th birthday has their own story, which could just as well be told in this or another film. The only backstory we discover at this point is Lucia’s. We hear that she was persecuted at some point – clearly, under Brazil’s military government of 1964-85 – and glimpse moments of her youthful sex life, as she fondly reminisces in telegraphic flashbacks.

We also learn here that her niece Clara is recovering from cancer – hence her cropped hair, which someone compares to the look of singer Elis Regina. The prelude serves, then, to signal that before the present, there was a past – and another past before that. It gives Mendonça Filho’s story historical density – a theme that strongly emerges when Clara shows interviewers a newspaper clipping found in the sleeve of a second-hand John Lennon LP, calling it “a message in a bottle”. Later, other fragments of information will be dropped in, more or less unobtrusively, to further sketch in this sense of history – as when Clara’s daughter reminds her that, at some point, she left her husband and children for two years. It is the only reference to this episode, but it tells us a lot about the tensions in Clara’s family, and about her emotional independence.

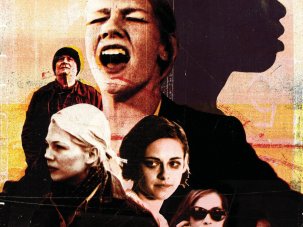

Another element providing a sense of history is the central performance by an iconic figure of the Brazilian screen, Sonia Braga. Known internationally for starring roles in Bruno Barreto’s Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands (1976) and Hector Babenco’s Kiss of the Spider Woman (1985), Braga became a national icon in various telenovelas of the 1970s, including the disco-themed Dancin’ Days. She came to embody a Brazilian archetype of the tough, sexually independent woman, and echoes of that image are evident here; her Clara is at once a strong, autonomous intellectual, a sensualist (a lover of the sea, of music, of dozes in her hammock) and a compassionate family matriarch. The film stresses her independence, making a strong case for the pleasures of living alone (with a visiting maid to make life easier), while also suggesting a more difficult dimension of solitude.

Braga’s charisma highlights Clara’s sexual power, with more than one man commenting on her beauty. Clara unreservedly enjoys her night with a gigolo recommended by a friend – like Sebastián Lelio’s Gloria (2013), the film stands up for the sexual pleasure of middle-aged to elderly women – though her anxiety about her mastectomy scar makes her back away from intimacy with a silver-fox widower. Clara is proudly aware of her own complexity (“I am an old lady and a child all together”), a complexity that is palpable, and not just because her musical tastes accommodate Villa-Lobos, Gilberto Gil and Queen. Making the most of her regal smile, raspy voice and hawkish profile, Braga’s imposing, tender, sometimes playfully mannered performance should by rights have earned her a nomination for the Best Actress award at Cannes.

While Aquarius might appear to be exclusively about the experiences of a privileged social sphere – working-class characters are less prominent than in Neighbouring Sounds – the film nevertheless offers an analysis of the political realities behind Recife’s luxurious facade (that the film was not selected as Brazil’s Academy contender this year is widely seen as government retaliation for the makers’ protest at Cannes against the impeachment of Brazil’s former president Dilma Rousseff). Aquarius opens with a series of stills showing the district’s magnificent skyscraper-lined shore, the image of chic Atlantic modernism, set to the lush orchestrations of Hoje, a ballad by the singer-songwriter Taiguara. But later, walking along the beach with her nephew and his girlfriend, Clara points out a pipe pumping sewage directly into the ocean: this, she says, marks the unofficial border between Recife’s rich and poor neighbourhoods.

Without over-explaining, the film suggests that beneath the elegance of Boa Viagem and, by implication, respectable Brazilian society, there runs an undertow of filth – made apparent by the faeces left on Clara’s staircase by the property developers pressuring her to sell her apartment. Late in the film, her journalist friend Ronaldo reminds her that they inhabit a profoundly compromised world, her own brother being involved in some kind of political ugliness. Corrupt power is represented by Diego, the handsome, faultlessly charming grandson of construction company head Geraldo; a well-mannered graduate from a US building school, he soon turns nasty, without ever dropping his smile, as Clara resists the coercive attempts to drive her out of her home (this brutal dynastic business enterprise, with strong church connections, has a distinctly Trumpian flavour). In a magnificently rebarbative characterisation from Humberto Carrão, Diego reveals his true nature when he expresses condescending respect for Clara’s family – “a family who fought to get where they are” – before adding, “a darker-skinned family”.

Sometimes shot in unobtrusively realist fashion, especially in the conversations, the film nevertheless opens up stylistically from time to time, making full use of the widescreen format – for example when the camera moves from events outdoors to pull back, passing over Clara dozing in her hammock, and pan across her flat, showing the interior’s porousness to light and sound from the outside world. There are also editing effects such as repeated Roeg-esque flurries of montage showing Clara with her gigolo, before closing her door and going to bed – moments that give this otherwise linear film an additional layer of rhythm and breathing space.

Given this stylistic elasticity, it is disappointing that the film ends abruptly with a somewhat crowd-pleasing moment of triumph, temporary at least, when – in a traditionally Loachian way – Clara gets one over on her oppressors. Dumping termites in their office may not solve her problems in real terms, but it provides a buoyant ending, and a striking final image. The earlier revelation of her flat overrun by insects – another of the construction company’s ploys – is a horrifying but oddly beautiful moment, their tunnels snaking over the walls like an elaborate art installation. The final close-ups of the creatures running in and out of their tubes make a bitterly ironic counterpoint to the opening images of radiant Recife: we finally discover one secret, unacceptable community lying beneath the visible one, and manipulated for its exploitation.

-

Sight & Sound: the April 2017 issue

Kristen Stewart, the star for our times, plus Paul Verhoeven and Elle, The Love Witch, Graduation, Jacques Becker and the range of Indian cinema.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.