Audrey Hepburn’s star has never really dimmed. A new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery brings us the Hepburn look across her various roles – actor, style icon, mother, humanitarian – at different stages of her life. One recurrent motif is her relationship with the couturier Hubert de Givenchy, whose designs she emblematised across the disciplines of fashion, photography and film.

Audrey Hepburn: Portraits of an Icon

2 July–18 October 2015 | National Portrait Gallery, London, UK

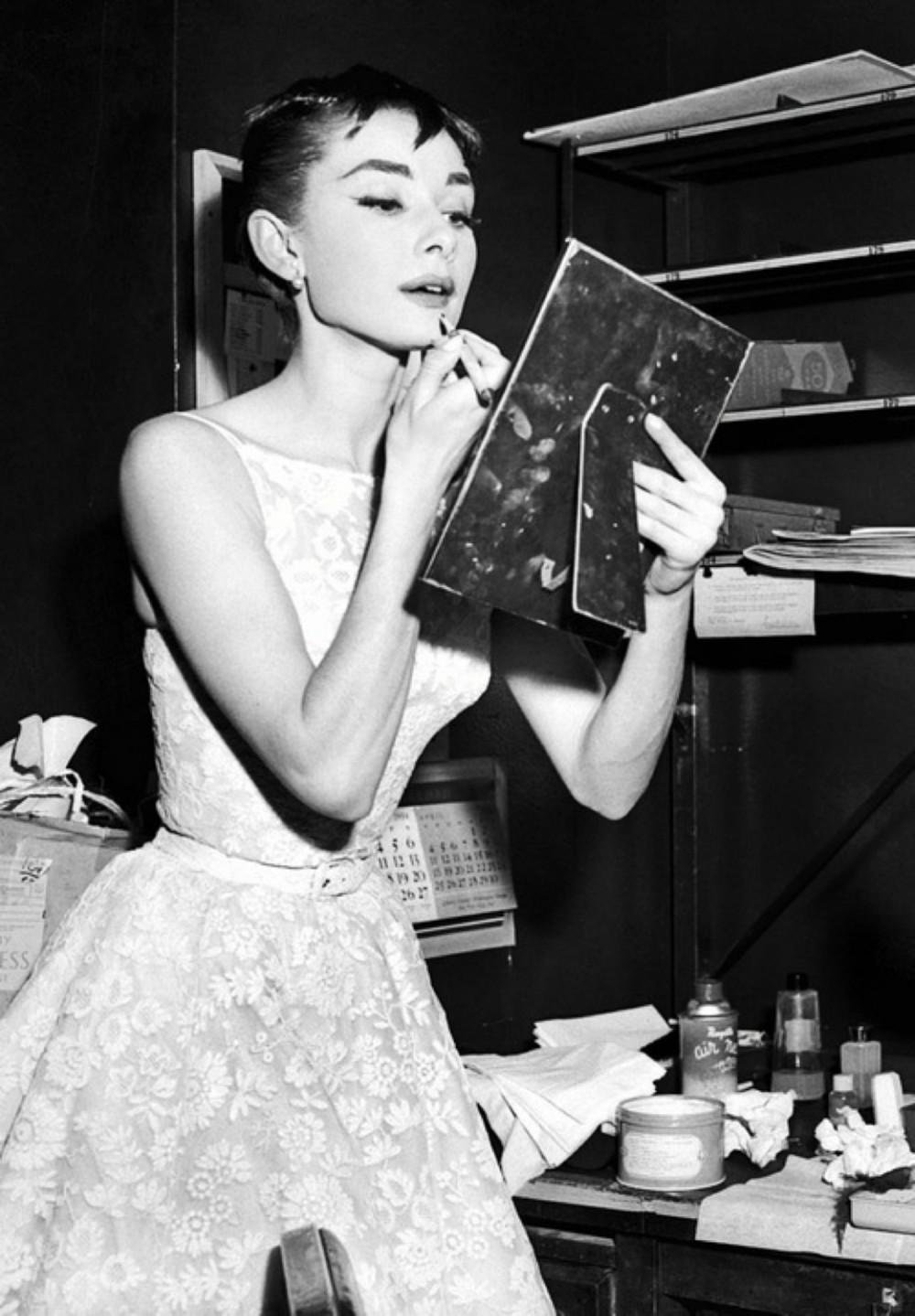

In 1954 Hepburn won an Oscar for her performance in Roman Holiday, her maiden starring screen role, playing a European princess who escapes her duties to lead Gregory Peck’s reporter on a merry tour of Rome. She accepted the award clad in a white floral sleeveless Givenchy gown with a narrow belt to emphasise her slender waist, an appearance which would become ingrained in Hepburn’s own mythology as well as as in the history of film-awards fashions.

This was an expression of Hepburn’s personal and professional friendship with Givenchy, a union that started the previous year when she filmed Sabrina in Paris. Hepburn had originally hoped to secure a gown from the designer Christóbel Balenciaga for the film, but Balenciaga turned her instead to his former student Givenchy. Though the latter had assumed that the visiting Hepburn would be Katharine, he was enthralled by Audrey’s elegance and they formed a lifelong bond: he would refer to Hepburn as his ‘sister’ while she would call him her ‘best friend’.

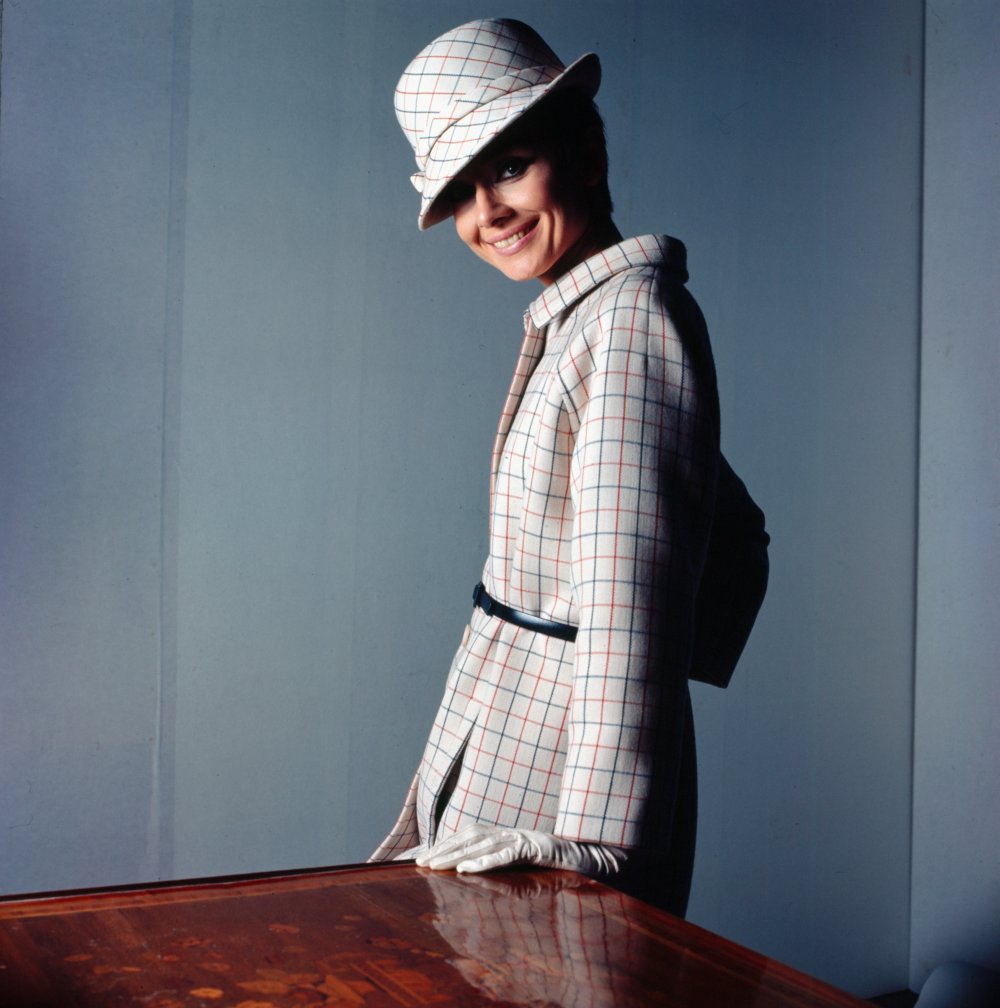

Audrey Hepburn in the Givenchy dress she wore when she won an Oscar for Roman Holiday in 1954

The fashion world soon picked up their bond. “We have a wonderful camaraderie,” Givenchy told British Vogue, while American Vogue discerned: “What fires his imagination races hers. The message he cuts into cloth she beams into the world with the special wit and stylishness of a great star.”

Reminiscing to Vanity Fair in 1995, two years after Hepburn’s death, Givenchy said:

“She gave life to the clothes – she had a way of installing herself in them, that I have seen in no one else since… [they] just adapted to her. Something magic happened. Suddenly she felt good – you could feel her excitement, her joy.”

The critic and film historian Alexander Walker, quoted in Drusilla Beyfus’s 2013 biography of Givenchy, meanwhile emphasised Givenchy’s role in honing not just Hepburn’s image but her career:

“It was from him that she acquired the cosmopolitan touch that distinguished from her the other young stars of the day. Such an education was much in evidence in her role in Vogue as Givenchy’s role model. Maybe we can see Givenchy as having something in common with Professor Henry Higgins, the character in My Fair Lady, based on George Bernard Shaw’s myth of Pygmalion. They both are seen to effect a transformation of Hepburn’s image: Higgins’s fictionally upon the character of Eliza, the Cockney flower girl, played by the star, the designer in reality in his influence on Audrey, his muse.”

What follows are Hepburn and Givenchy’s eight screen collaborations as we see how they came to define Hepburn’s films, establish Givenchy’s reputation as one of the greatest cinematic couturiers and cement Hepburn’s status of one of the foremost style icons of the twentieth century.

Sabrina

Billy Wilder, 1953

Sabrina (1954)

Though Sabrina is now remembered for establishing the Givenchy/Hepburn partnership, the majority of Hepburn’s costumes were the responsibility of esteemed costume designer Edith Head, who won an Oscar for her work. It was Givenchy, however, who created the film’s centrepiece costume, evidenced after Sabrina’s transformation from chauffeur’s daughter into a chic Parisienne who pines for married playboy brother (William Holden) while pursued by his brother (Humphrey Bogart).

The white strapless ball gown, a style very similar to Hepburn’s Academy Awards dress, has a strong fairytale aesthetic, and Sabrina’s attendance at the ball is very much her Princess moment.

Offscreen it also signalled a new direction for fashion. Hepburn’s dancer’s physique was the antithesis of the voluptuous curves then in favour, and wardrobe departments usually concealed her very slim and long-necked body under voluminous items. Whereas her wardrobe in Roman Holiday sheathed her prominent collarbone with a button-up shirt and scarf around the neck, Givenchy structured gowns that displayed her svelte proportions. The dress directs the eyes to Hepburn’s narrow waist and slim upper torso, while the embroidery ensures that your eyes follow every inch of the design.

According to Wilder’s co-screenwriter Ernest Lehman, “The way Audrey looked in Sabrina had an effect on the roles she later played. It’s fair to say that if she had never gone to Paris she wouldn’t have had that role in Breakfast at Tiffany’s…” Hot on the heels of Roman Holiday, Sabrina was Hepburn’s own Cinderella moment: she had arrived in Hollywood.

Funny Face

Stanley Donen, 1957

Funny Face (1956)

A skilled dancer who had taken ballet lessons since she was a child, Hepburn was a good fit for this fashion world-set romantic musical. She plays Jo Stockton, a bookseller (clad in the boho uniform of polo-necked sweater and skinny black trousers) who is whisked away to Paris by Fred Astaire’s fashion photographer. Once again Edith Head designed the majority of the costumes, but the custom dresses into which Jo metamorphoses were entrusted to Givenchy.

Especially worth noting is Givenchy’s design for Jo’s bridal dress. A slight departure from the usual long length and strapless style he had previously favoured, it is shorter, with netting for a puffed-out effect, a high, scooped neckline and capped sleeves, slightly similar to what have since become referred to as ‘prom style’ dresses due to their associations with the 1950s. We can think of it as an updated version of Sabrina’s Cinderella gown.

Love in the Afternoon

Billy Wilder, 1957

Love in the Afternoon (1957)

In her second romantic comedy with Billy Wilder, Hepburn is a cello player who poses as a femme fatale to prevent the murder of Gary Cooper’s American businessman at the hands of his lover’s husband.

Rather than clothe her in revealing garments, the uncredited Givenchy created pieces that that would retain her character’s elegance and flatter her shape while capturing the attention of her elder-gentleman suitor with a hint of provocation. The designs cuminate in a white point d’espirit ball gown, accentuated with a detailed trim and bow at the waist, which she wears to the opera.

Charade

Stanley Donen, 1963

Charade (1963)

This Paris-set romantic comedy/mystery/crime caper offered audiences a visual feast of Hollywood glamour through its leads of Hepburn and Cary Grant, supported by stars including Walter Matthau and James Coburn.

Givenchy dressed Hepburn in contemporary styles now very evocative of the era, including a selection of elegant high-buttoned jackets, coats and raincoats, sleek pencil skirts and shift dresses in colours of red, cream, mustard and black, all accentuated with accessories – hats, gloves and scarves – of equal importance. The image of Hepburn in a red suit and pillbox hat walking the banks of the Seine with Cary Grant has become of one the film’s most enduring images.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s

Blake Edwards, 1961

Breakfast at Tiffany's (1961)

It is the moment that defined Hepburn’s career: when Holly Golightly decamps from a taxi on a New York morning, still dressed in the pearls and little black cocktail dress from the previous evening, to glance in the window of Tiffany’s jewellers while sipping her morning coffee and pastry, her eyes clad in oversized dark sunglasses. Hepburn’s Givenchy dress soon became one of the fashion world’s most sought-after items and her style continues to be emulated over 50 years on.

Givenchy kept Golightly’s look simple and chic and the epitome of elegance with the chignon hair, pearls and long black gloves, successfully disguising her taboo profession. He took his inspiration from Coco Chanel’s innovation of the little black dress, which evolved from her 1925 ‘garçonne dresses’. This was a looser, more ‘boyish’ style that heralded a new era for women’s dresses, one when women could enjoy their clothes having more freedom and movement without the structural trappings of corsets.

After filming completed Givenchy donated the dress to writer Dominique Lapierre and his wife to auction for their Calcutta charity; it sold for £140,000, double the expected sum. The dress was auctioned again for £427,600 in 2006, when Christie’s description noted:

“The sleeveless, floor-length gown with fitted bodice embellished at the back with distinctive cut-out décolleté, the skirt slightly gathered at the waist and slit to the thigh on one side, labelled on the waistband Givenchy; accompanied by a pair or black elbow-length gloves [made later]; an envelope addressed in Givenchy’s hand to his friends Monsieur Dominique Lapierre in Paris; and a November 2006 U.S. edition of Harper’s Bazaar magazine, the cover featuring Natalie Portman modelling the dress in this lot.”

In 2010 Givenchy’s design placed top of a LoveFilm survey of The Greatest Female Movie Outfits of All Time.

Paris – When It Sizzles

Richard Quine, 1964

Paris – When It Sizzles (1964)

Paris – When it Sizzles falls into the more understated category of the Hepburn-Givenchy union, the star largely costumed in elegant two-piece suits and shift dresses as she was playing a secretary to William Holden’s playwright. Still, it’s hard to forget the ‘perfume’ credit given Givenchy at the start of the film (something recently replicated in Peter Strickland’s The Duke of Burgundy). The couturier’s perfume was an exclusive gift for his muse, never reproduced.

How to Steal a Million

William Wyler, 1966

How to Steal a Million (1966)

With her heavily kohl-lined eyes, short beehive hairstyle and wrist-length gloves, Hepburn had never looked more ‘60s’ than in opposite Peter O’Toole in Wyler’s Parisian heist comedy. Still, the trademark Hepburn/Givenchy elegance persisted under the film’s modishness. Hepburn continues to be the perfect muse and palette for Givenchy’s creations and makes quite the entrance in her all-white ensemble of jacket and skirt, large white-rimmed glasses – much like those of Breakfast at Tiffany’s – and white pillbox hat. As she drives into the frame and emerges from her tiny red Autobianchi, the humorous aesthetic immediately sets the tone for the ensuing frivolity.

Love Among Thieves

Roger Young, 1987

Love Among Thieves (1987)

In this made-for-television production Hepburn stars as baroness Caroline DuLac, a concert pianist who flees to the Latin American city of Ladera after stealing three Fabergé eggs from a San Francisco museum. The film borrows liberally from Hepburn’s past crime capers, and so too Givenchy’s costumes from his previous designs, most noticeably a red dress that evokes the one Hepburn wore in Funny Face. The films were 30 years apart yet Hepburn’s grace and Givenchy’s couture proveds a timeless combination.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.