A gay, white, corporate lawyer (Tom Hanks), who is fired from his white-shoe firm when his bosses discover he has Aids, hires a homophobic, black, storefront lawyer (Denzel Washington) to defend him in the discrimination suit he brings against his former employer. Nothing if not high concept, Philadelphia, directed by Jonathan Demme, is the first major Hollywood movie to deal with Aids since the disease was first recognised in the US in 1981. In that sense, it has been 13 years in the making and bears the burden of all the films that have not preceded it.

It is standard wisdom within the industry that ‘difficult’ films – and the presence of two major stars notwithstanding, a film about Aids is difficult – are review-driven. If Philadelphia had relied on the critics to bring audiences into the cinemas, it would have bombed in a week. Most reviews were not only tepid, they were wildly off the mark. Even the critics who were supportive overlooked most of what is interesting in the film. Philadelphia was dismissed as “too packaged” (as if films costing over $25 million weren’t always produced with an eye on demographics). Demme was scolded for leaving on the cutting-room floor the scene in which Hanks and Antonio Banderas, who plays his longtime companion, kiss on the mouth. The script was scorned as agit-prop and the characterisations as one-dimensional.

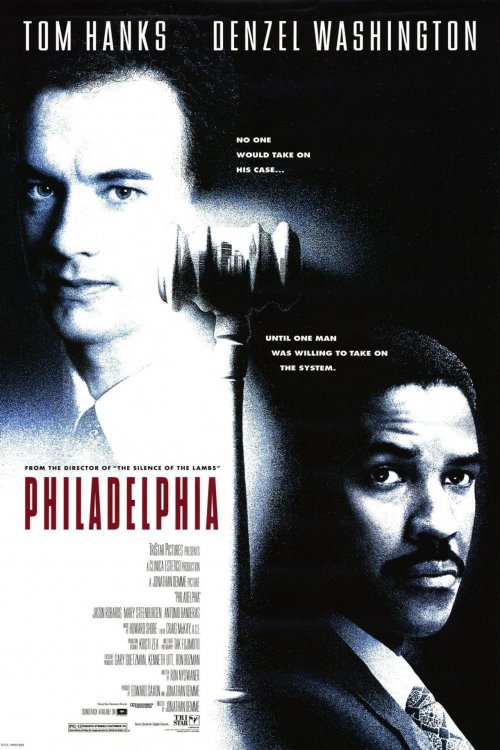

The US poster for Philadelphia (1993)

To be fair, some critics, myself included, were irritated before they saw the film by TriStar’s schizoid advertising campaign. “No one would take on his case until one man was willing to take on the system” was the catch-line on full-page press advertisements that showed a healthy-Iooking Hanks and a poker-faced Washington with a gavel and a bit of Philadelphia skyline between them. This last-minute strategy to sell the movie as a generic discrimination case seemed not only cowardly but silly, considering the Aids angle had been at the centre of newspaper and magazine coverage for over a year and that Hanks, Demme and Washington had all given interviews in which they, at least, pulled no punches.

Demme was also burdened by his double-edged reputation. Those who pigeonholed him as a quirky independent seemed astonished that he hadn’t spent TriStar’s millions to make an American Savage Nights. Others thought that he was atoning (though insufficiently) for having coded the serial killer Buffalo Bill in The Silence of the Lambs as a gay man. Demme still denies that there are aspects of that character that could be read as gay (and I agreed until I went to a screening where people in the audience yelled “Kill the faggot” when Jodie Foster undid the safety catch on her gun). But he allows that the attack on the film by gay rights activists made him aware of the lack of positive gay characters in movies.

The ‘positive gay image’ dilemma haunts Aids films as different as Longtime Companion (Norman Rene, 1990), criticised for confusing positive with bourgeois and prudish, and The Living End (Gregg Araki, 1992), which flies in the face of the positive-image brigades with its pair of narcissistic nihilist wannabes. Earlier this season the HBO adaptation of And the Band Played On (Roger Spottiswoode, 1993), a sharply scripted attack on the Reagan administration’s Aids policy, turned laughable during a scene in a gay bathhouse that looked like a yoga retreat.

As Torn Hanks plays him, Andrew Beckett is a very appealing guy and, fortunately, much too complicated to fit whatever one might imagine a positive image to be. But Demme’s expressed concern about positive images skews his depiction of Andrew’s large suburban family, every member of which offers him nothing less than unconditional love. It also makes him wary of showing sexual intimacy between Andrew and his lover Miguel (although they dance cheek to cheek and, when Andrew is dying, Miguel kisses his fingers one by one). From a gay perspective, it would have been an affirmation to show Andrew and Miguel at least sharing a bed. And if such a sight had sent die-hard homophobes running from the cinema, so what? Philadelphia stops short of confronting straight viewers (to whom it is primarily addressed) with the kind of images that might trigger their homophobia. That’s a failing, but it doesn’t cancel out everything else the film has to offer.

Colour blindness

As for the packaging quibbles, the same critics who objected to the packaging of Philadelphia had no such problem with Schindler’s List, which wears the mantle of Steven Spielberg as if it were the Shroud of Turin. It is not just their concurrent release that makes comparison between the two inevitable. Where Philadelphia constructs a narrative about Aids around a straight, homophobic lawyer’s coming to consciousness, Schindler’s List filters the experience of the Holocaust through a Nazi entrepreneur who saves over a thousand Jews. But unlike Philadelphia, which keeps its gay character in the foreground, Schindler’s List presents the Jews as an anonymous mass, the background for Schindler’s transformation.

Generically speaking, Philadelphia is a women’s picture crossed with a courtroom drama. Like Camille, Andrew Beckett is mortally ill in the first reel and expires in the last – but not until a jury of his peers has rendered a verdict in his favour. Philadelphia may be more mainstream than Demme’s previous films (it’s about the possibility of human connection rather than the inevitability of isolation), but like The Silence of the Lambs (1991) or Melvin and Howard (1980), it’s an odd-couple story. The high-voltage relationship is not between Andrew and his lover, but between Andrew and Joe Miller (Washington), the lawyer who reluctantly agrees to handle his case.

Though Andrew is the showier part (Hanks, who goes through a physical transformation in the course of the film nearly as extreme as De Niro’s in Raging Bull, is likely to win the Oscar), Joe is the central character. The narrative of Philadelphia is less about being gay and living with Aids than about being heterosexual and homophobic. Joe comes to understand how his homophobia, which he regards as integral to his manhood, underlies his fear and loathing for people with Aids. But Philadelphia is a breakthrough film not only because it deals with Aids and homophobia, but because it is the first major non-action Hollywood movie in which a black man personifies mainstream America. Joe’s homophobia is a sign of his normality (he’s a regular Joe); Andrew’s white skin privilege is cancelled by his homosexuality and his disease.

Casting Washington in the lead guaranteed the film the black audience that otherwise might not have had much interest in the problems of a rich white homosexual with Aids. But Aids is rampant in inner cities, where it attacks not just gay men, but IV drug users and women. Regardless of how the disease is transmitted, homophobia has everything to do with its public perception, and homophobia is no less virulent among blacks than among whites. A homophobic society didn’t create Aids or direct its early demographics, but it uses the epidemic as proof that homosexuality is a contagion.

What is interesting here is not that black audiences are corning to see Washington; it’s that white audiences are reacting to him and to the film in a colour-blind way. Joe is not the first black character to represent family values (in that respect he’s similar to the Danny Glover character in the Lethal Weapon series), but he is the first both to represent family values and to run the show (Glover played second to Mel Gibson’s borderline rogue male) in a film that is not primarily about black identity (Joe is not Malcolm X). That Joe is African-American complicates his relationship to Andrew. He understands Aids discrimination from his own experience of racial discrimination (that is one of the reasons he takes Andrew’s case), but having struggled for middle-class status he is desperate to keep a distance between himself and someone who is perceived as a social pariah.

As Brecht discovered during his exile in Hollywood, agit-prop is a form without honour in America. Middle-brow wisdom has it that a film or a novel can take a political position only so long as no one comes out and says what that position is. That so much of Philadelphia has the ring of agit-prop indicates either courage or naivete on the part of the filmmakers. But despite its determination to impart useful information about constitutional rights, homophobia and living with Aids in every scene, Philadelphia is not simply a political tract.

Passion for life

Demme combines a script (written in collaboration with Ron Nyswaner) that could have been produced as an after-school television special with an expressionist mise en scène no less gripping in its effect than that of The Silence of the Lambs, and then throws in a few scenes shot documentary style for good measure. It is the hybridity that makes the film formally interesting. Hanks and Washington, who are never less than movie stars, play scenes with people who may or may not be professional actors, but who actually have full-blown Aids. Supporting parts are played by performers from the avant-garde theatre (notably Anna Deavere Smith as a token black para-legal and Ron Vawter as the only Jewish, liberal partner in Andrew’s firm) and by members of Demme’s family. The mix-and-match casting suggests one of the film’s major themes: that to be fully human means to recognise and respect the difference of the other.

As in The Silence of the Lambs, there are an extraordinary number of extreme close-ups and shot-counter-shot sequences between the two main characters in which their faces, shot frontally and slightly from below, loom out of the shadows, seemingly close enough to touch. Philadelphia is an extremely tactile movie. Demme is out to make the audience as aware of Hanks and Washington’s physicality as they are of each other’s.

An attraction/repulsion dynamic, similar to that between FBI trainee Clarice Starling and genius serial killer Hannibal Lecter, connects Joe and Andrew. If the terror of contagion in The Silence of the Lambs had to do with the psyche (Clarice is warned that Lecter could infect her mind), here it is about the body – Joe’s fear that he can be invaded not only by Andrew’s disease, but by his sexuality. In The Silence of the Lambs, Clarice learns that Lecter is best kept at a distance. At the end of Philadelphia, however, Joe sits on Andrew’s hospital bed and adjusts the dying man’s oxygen mask. Considering that when Joe first learns that Andrew has Aids he pulls away from his handshake as if he’s felt shit on his fingers and then runs to the doctor to find out if he could have caught the disease by being in the same room as someone who has it, he has come a long way.

Despite the close-ups that put the actors in the viewers’ laps and the percussive use of camera movement, Philadelphia is extremely theatrical: it seems like opera. That is an effect of the frontality of the blocking and of the actors’ gaze (not directly into camera, but sometimes deflected by as little as ten degrees). And the scenes are as disjunct as those of opera – one remembers them as recitatives, duets, arias.

The climax of the film comes in the only scene that is inflected with subjectivity. Joe has stayed behind after a party in Andrew’s loft to coach him in the testimony he is to give in court the next day. But Andrew is less interested in his case than in showing Joe the place where he really lives. He has put on a recording of Maria Callas singing La mamma morta from Andre Chenier. Wheeling the stand to which his IV drip is attached around the floor, he begins to translate the lyrics: “I am life, I am love, I am oblivion.” Embers are still glowing in the fireplace, but that doesn’t account for the crimson light that floods the room. Demme shoots Hanks from an angle high above his head, as if the music had transported him. Hanks’ performance is extraordinarily subtle – only for a second or two does Andrew become so caught up in the aria that he crosses the line from evoking the diva to embodying her. Had he been alone and doing this performance for himself, he might have acted with more abandon. But he is not alone, as the reverse-angle cutting of the scene emphasises. He is trying to communicate something about himself as Andrew while taking into consideration Joe’s limitations and not giving him more than he can take. (Despite the close-ups, Philadelphia is no more an in-your-face movie than Andrew is an in-your-face kind of guy.)

Even so, the baldness of the emotion terrifies Joe, who makes a fast retreat. Outside he hesitates, goes back to the door, starts to knock, hesitates again, and finally flees in confusion to the comfort of his wife and child. But Washington makes it clear that it isn’t comfort Joe finds. As he clutches his family, we still hear Callas in the background, evoking inchoate feelings of mortal dread and passion for life.

In a more sentimental film, Joe would have hugged Andrew and homophobia would be irradicated forever. Instead, Demme lets us understand that what Joe has seen in Andrew and been moved and shaken by, and even envious of, is everything Joe has repressed in order to be a man. It is a feminine desire (the mother’s desire and the desire for the mother). And for a man to give way to that is to transgress the law of the father; it leads to castration and death. For Joe, to embrace Andrew is to risk losing everything – his wife, child, heterosexual male identity and the privilege this confers.

Homophobia rules

Set in the ‘city of brotherly love’ and the ‘cradle of American democracy’, Philadelphia takes the courtroom as its main arena. The principles invoked there are set down in the constitution, the Bill of Rights and the Declaration of Independence: “That all men are created equal and that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights: that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” “Nowhere in the constitution does it say that ‘all straight men are created equal’,” is Joe’s retort to the gauntlet of homophobic demonstrators outside the courtroom. Joe’s passionate argument convinces the jury that Andrew has been discriminated against because he is a homosexual with Aids, and that in discriminating against him the law firm which employed him violated his constitutional rights.

But Joe can advocate for Andrew’s constitutional rights and still be a homophobe. He tells the jury as much: “I feel like you do [about homosexuals] but it’s against the law [to discriminate against them].” The constitution notwithstanding, homophobia and racism are the rule in America. That is why the Callas scene is so important: it shows that the struggle against homophobia doesn’t begin and end in the courtroom. Philadelphia may be a package, but it refuses to tie up its loose ends.

Jonathan Demme in the Sight & Sound archive

Get access to our digital archive for more of our writing about the films of Jonathan Demme, including:

Caged Heat

Review: Monthly Film Bulletin December 1975, page 258

Crazy Mama / Crazy Ladies

Review: Monthly Film Bulletin April 1981, pages 64-65

Fighting Mad

Review: Monthly Film Bulletin August 1976, page 165

Citizens Band

Review: Monthly Film Bulletin November 1978, page 216

Last Embrace

Review: Monthly Film Bulletin November 1980, page 216

Melvin and Howard

Review: Monthly Film Bulletin April 1981, page 72

Swing Shift

Review: Monthly Film Bulletin December 1985, pages 390-391

The Perfect Kiss

Review: Monthly Film Bulletin September 1985, page 295

Something Wild

Feature: Sight & Sound Winter 1986/87, pages 30-31 (considered with True Stories and Blue Velvet)

+ Review: Monthly Film Bulletin July 1987, pages 217-219

Swimming to Cambodia

Review: Monthly Film Bulletin September 1987, page 284

Married to the Mob

Review: Sight & Sound Summer 1989, pages 210-211

+ Review: Monthly Film Bulletin July 1989, pages 209-210

The Silence of the Lambs

Review: Sight & Sound June 1991, pages 53-54

+ A.L. Kennedy column: Sight and Sound June 1995, page 34

Philadelphia

Review: Sight & Sound March 1994, pages 45-46

Storefront Hitchcock

Review: Sight & Sound January 1999, pages 57

Beloved

Review: Sight & Sound March 1999, pages 34-35

The Truth About Charlie

Review: Sight & Sound August 2003, pages 60, 62

The Manchurian Candidate

Review: Sight & Sound December 2004, pages 55-56

Rachel Getting Married

Preview: Sight & Sound November 2008, pages 24-32

+ Review: Sight & Sound February 2009, pages 69-70

Ricki and the Flash

Review: Sight & Sound October 2015, page 95

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.