Spoiler alert: this article reveals many plot turns in Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia.

Sam Peckinpah’s work, made over a brief, intense career, can be divided into three unequal parts. The first is comprised of three films – The Deadly Companions (1961), Ride the High Country (1962) and Major Dundee (1964) – which announced his remarkable talent as a filmmaker, but also provided his enemies with the ammunition to portray him as difficult, erratic and undisciplined. As a result, he would spend the better part of the next three years following Dundee essentially blacklisted as a feature director.

Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia screens on Friday 21 and Monday 24 August 2015 in the National Film and Television School’s Passport to Cinema strand at the BFI Southbank, London.

A Sam Peckinpah retrospective runs 5-15 August 2015 at the Locarno Film Festival, Switzerland, with talks and introductions by guests including Garner Simmons, Katy Haber and more.

Desperate to prove himself, he eventually was forced to return to television where he had first made a name for himself directing half-hour westerns. Hired by producer Daniel Melnick to adapt and direct Katherine Anne Porter’s dark novella Noon Wine for ABC Stage 67, Peckinpah was once again able to demonstrate his considerable gifts. On the strength of this film and his original promise as filmmaker, Warner Brothers was persuaded to take a chance on him, hiring him to rewrite and direct a moderately budgeted western called The Wild Bunch.

Shot in 1968 and released the following year, The Wild Bunch marks the beginning of the second and most productive period of his creative life. It was followed by The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970), Straw Dogs (1971), Junior Bonner (1972), The Getaway (1972), Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (1973) and Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974): seven films in less than seven years. Challenging, emotionally intense and extremely personal, each stands alone; no two are alike. Indeed, his original vision and unwillingness to conform was both Peckinpah’s problem and appeal. Despite being typed early on as a director of westerns, Peckinpah continually broke the mould, defying easy stereotypes. Attempting to dismiss him, his critics labelled him as ‘Bloody Sam’, pointing to his use of violence and falsely decrying it as gratuitous while failing to explain the simple humanity of a film like Junior Bonner or the lyricism of Cable Hogue.

As for the final four films of Sam Peckinpah’s body of work, they sadly demonstrate the destructive impact of cocaine upon a creative genius. The Killer Elite (1975), Convoy (1978) and The Osterman Weekend (1983) all contain flashes of brilliance but without Peckinpah’s earlier sustained vision. Only Cross of Iron (1977) stands out as worthy of serious critical appraisal. Significantly, that is the result of being shot in Yugoslavia where harsh anti-drug laws forced Peckinpah to put aside his mounting addiction to cocaine and return to alcohol to keep his demons at bay while directing.

Sam Peckinpah and cast members on the set of Cross of Iron (1977)

Thus, the most exceptional film in Sam Peckinpah’s remarkable body of work becomes not Ride the High Country or The Wild Bunch, films which have traditionally been singled out by most critics as quintessential examples, but Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia. Coming as it does at the end of his most productive period, Alfredo Garcia is the true culmination of all his creative forces. A highly personal and uncompromising film, it is like no other. Dismissed by most critics upon its release and unfairly maligned in some quarters even today, it nevertheless demands our attention as a significant and seminal work of art by a major filmmaker. For at its core, Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia is less an action adventure than a love story.

~

As a graduate student in Northwestern University’s Department of Radio/Television/Film, I had the good fortune to have as my adviser the late Stuart Kaminsky. The author of Don Siegel: Director, Kaminsky had managed to get Sam Peckinpah to write the afterword for his book in order to assuage the fears of his publisher. As a result, he was able to obtain for me the phone number for Peckinpah’s bullet-riddled trailer in Paradise Cove, a beach community north of Malibu.

The year was 1973, and I called him cold. It was a little past noon on the West Coast, so naturally I woke him up. Still recovering from the aftereffects of a brutal war of attrition with MGM’s James Aubrey over Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, Peckinpah wasn’t in much of a mood for conversation, so I did most of the talking as I attempted to persuade him to allow me to write a book on his life and films. His silence lengthened. I ran out of things to say. The silence continued. At last, he suggested that if I were really serious, I should send him whatever I had and he would let me know. Then he hung up.

Obviously he had neglected to say where to send it. That was a test. The first of many obstacles designed to question my resolve and test my resourcefulness. How I met and successfully passed these challenges are recorded elsewhere, principally in the book I would eventually write, Peckinpah: A Portrait in Montage (1982, revised 1998). In the end, he rewarded my persistence by suggesting I meet him in Mexico City.

We met in the lobby of the Aristos Hotel. It was mid summer, the first day of prep on what was to become Peckinpah’s next feature film, Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia. Based on what I had sent him to read along with that initial meeting, he invited me to join him as he scouted locations, met with actors and key members of the crew including Mexican cinematographer Alex Phillips, Jr.

Sam Peckinpah filming Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia with cinematographer Alex Phillips

In truth, the Peckinpah I met that first time in Mexico City did not strike me as someone capable of the legendary mayhem and madness generally attributed to him. He seemed fragile, not at all what I had expected. Clearly suffering from the aftereffects of his battles with MGM over Pat Garrett, his health was so poor that if a month or so later I had opened a newspaper to find Peckinpah’s obituary, I would not have been surprised. Yet as pre-production moved ahead, Peckinpah seemed to grow stronger each day. It was as if the filmmaking process itself were the only elixir capable of restoring his health. Indeed, as I would eventually come to realise, everything else in his life came second.

A few days after my arrival, after the Mexican censors had finally cleared the film’s script and given it their stamp of approval, Peckinpah handed me a copy to read. Given its provocative title, I was clearly intrigued. Co-written with Gordon Dawson (who would also co-produce) from an original story idea by Frank Kowalski, it had been sold to producer Martin Baum and eventually the studio as a dark and violent action adventure – in short, A Sam Peckinpah Film, with all that that implied. Returning to my hotel that night, I sat down and immediately began to read. As with other Peckinpah films, the story intentionally opens with misdirection:

EXT. A WALLED HACIENDA – DAY

IS IT SPAIN – Maybe Italy – or possibly MEXICO – or BRAZIL – or ARGENTINA – or…? It is not Mexico.

In any case, we are far enough away to see the expanse of the large complex of buildings and stables, far enough not to see too may details.

Specifically, we see horses, specifically we do not see automobiles. Specifically it is a pastoral scene of great wealth…

Like soldiers who turn out to be outlaws or deer grazing in what turns out to be a prison compound, the opening ten minutes of Alfredo Garcia mislead us to believe we are in the 19th century American Southwest. As a young pregnant daughter is brutally forced to betray her lover’s name, and her father (referred to in the script simply as ‘El Jefe’) places a million-dollar bounty literally on the offender’s head, the script abruptly shifts to the present day:

EXT. HACIENDA – A SERIES OF ANGLES – DAY THE MEN LEAVE. BUT NOT BY HORSE. MERCEDES, FERRARIS, CORVETTES… (page 6)

And thus we find ourselves propelled into the twentieth century. As a precondition of the Mexican Board of Censor’s approval, much is made of jet planes taking off and landing as they scour the globe in search of Alfredo Garcia. Eventually, El Jefe’s men arrive in Mexico at an out-of-the-way tourist trap described as:

INT. SIEMPRE VIVA BAR – NIGHT

A THIRD-RATE CLUB COMPLETE WITH FOUR GIRLS (waitresses?), a bandstand and a piano player.

THIS IS BENNIE, WHO PLAYS AND HANDLES THE CUSTOMERS.

BENNIE ISN’T BIG, BUT LOOKS LIKE HE COULD BE ROUGH. BUT HE ISN’T HALF ROUGH. He’s not going soft – he’s gone soft. Maybe he’s always been soft, but in any case he’s learned to be friendly enough to talk his way out of more fights than most men can find.

He’s near the wrong side of 40 and is the only gringo bartender on the Mexican side of the border who can’t speak decent Spanish… (page 8)

Two bounty hunters – Sappensly and Quill (Robert Webber and Gig Young) take the lead. They show Bennie a photo of Alfredo. Immediately recognising the picture as the former lover of Elita, the woman he now lives with, Bennie plays along, promising to let them know if he sees him. After they leave, Bennie goes to confront Elita, who confesses that Alfredo was her first lover, long ago. And while it is true she was with him recently, he died in a car crash and is buried in a remote village.

Elita (Isela Vega) and Bennie (Warren Oates)

Recognising the opportunity, Bennie immediately seizes on it. There is a price on the head of a dead man. All he has to do it return with Alfredo’s head as proof he’s dead and the money is his. A chance at a fresh start for both Bennie and Elita. So he makes a bargain with El Jefe’s henchmen. Then he and Elita set out to on their dark and troubling quest.

Just as we begin to settle into a story we think we know, Peckinpah takes us in a totally unexpected direction. What originally seemed like a straightforward action adventure abruptly shifts becoming a complex, multilayered love story – totally unpredictable. A vivid, unsettling exploration of the true meaning of love and the consequences of allowing it to slip away.

Peckinpah starts with two unlikely lovers. Neither is young. Bennie (played by Warren Oates) is a loser described in the script as having “…gone through 40 years of life with a $1.35 in one hand and an erection in the other and now, when it’s time to find out which is which, he doesn’t want to look.” Elita, on the other hand, is a sometime prostitute and part-time actress, who loves him despite his failings. Here is how Peckinpah introduces her in the script as she spots Bennie entering the bar and brothel where she is working as a hostess:

SHE SEES HIM AND REACTS HAPPILY. Elita [once] was capable of giving herself for money, but you know now you can’t buy her. Her life with Bennie is the first happiness she’s had in years.

He is all things to her – a trusted friend and lover. She prays for him and herself in a clear, hopeful way. Elita is a purist. Maybe is also a little past 30 – maybe not.

Before arriving in Mexico, Peckinpah had already cast Oates as Bennie. In fact, he had intentionally shaped the script to take advantage of Oates’s intense, offbeat screen presence. Character actor turned leading man, Oates was not a traditional Hollywood star. His face had a lived-in, world-weary quality that was more reminiscent of Humphrey Bogart than William Holden (who had played Pike Bishop in Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch). In fact, as has been noted more than once, over the course of Alfredo Garcia Oates bears a more than passing resemblance to Peckinpah himself.

Warren Oates as Bennie

However, the casting of Elita was more complicated. Soon after settling in to the Aristos Hotel, Peckinpah met with casting director Lonka Becker, who arrived with a stunningly beautiful young Mexican actress in her early twenties. Calling himself ‘San Samuel’, Peckinpah charmed and flirted with both Lanca and her protégé but remained non-committal. Over the course of several hours, other young ingénues came and went. With each, Peckinpah attempted to explain what it was he was looking for. Elita, he said, was a woman of complex emotions whose beauty radiates from within. He asked Lanca about Aurora Clavel, the actress he had previously cast as Pike Bishop’s lover in The Wild Bunch as well as Pat Garrett’s wife in Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid. Brightening, she assured him the actress would be there shortly.

When Clavel finally arrived, Sam met her with a warm embrace. As they discussed the role, Peckinpah asked her to remove her makeup. When she did, he turned to the two American members of the preproduction team he had brought with him to Mexico – co-writer/producer Dawson and first AD/production manager William C. Davidson – and said: “You see…? This is Elita.” With the casting session over, Peckinpah asked Dawson to be sure to include Aurora among the actresses he would screen-test with Oates later in the week. Then, saying goodnight to the others, he asked Aurora to remain.

In the corridor, Davidson looked confused. Why waste money on screen tests if Peckinpah had already decided on Clavel? Dawson shook his head: “Until Sam can actually see them with Warren, nothing’s set in stone.” Indeed, after the half-dozen tests, it would not be Clavel but Isela Vega who could convey the earthiness of Elita that Peckinpah was after. In her mid-thirties and fearless, she brought an ethnic authenticity to the role. And working with Oates, she lit up the screen.

Elita (Isela Vega) and Bennie (Warren Oates)

The casting of Vega was the first indication that Peckinpah was interested in making an unconventional love story. By de-coupling love from sex, he begins to explore the true nature of the complicated relationship between a man and a woman. As their quest begins, Bennie believes that money will solve all their problems. Elita disagrees but goes along because she cares for him and believes in her heart that she can change him. It is an uncertain journey.

Stopping along the side of the road, they have an intimate picnic in a grassy field beneath the shade of a tree. As written, it is a scene where they begin by confessing their dreams and hopes for the future. It is here that Elita asks Bennie why he’s never asked her to marry him. As Bennie struggles to answer, she says: “So ask me.” And because he can’t say no, he does. But clearly neither believes he really means it.

Changing the subject, Bennie attempts to explain why they need to find Alfredo’s grave. Without explicitly saying how they will do it, he explains that proof of his death is worth $10,000 – a chance for them to go away together, to make a new start. Troubled by the implication that they may have to desecrate a grave, she suggests that he could not possibly want her to take part in such an act. But Bennie insists: she already is part of it, and if she can’t do it for Bennie, she should do it for Alfredo because he would have wanted her to be happy. Passing a bottle of tequila, they drink a cynical toast to Alfredo and happiness.

Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974)

As written, this is where the scene ends. But in filming it, Peckinpah, without telling Oates beforehand, instructed Vega to go beyond what is on the page. Challenging Bennie, she says that if he really means it, he will ask her again to marry him. Caught completely unprepared, Oates never breaks character. We see in his face the realisation that despite all his procrastination and inability to commit, he in fact does truly love her. We watch Oates as Bennie, thus struggling with his emotions, ask her again, only this time speaking from his heart. And we see Isela, now completely immersed in the character of Elita, give in to her emotions. In this remarkably candid moment, it is no longer a scene about Alfredo or money or anything except the love between two people. She curls in against him and he holds her tight. It is as nakedly emotional and honest a love scene as has ever been filmed. And in it hangs the balance of the entire film.

The sequence of events that follows is unpredictable and exceptionally complex. That night, Bennie and Elita decide to camp out under the stars only to be accosted by two American bikers, identified in the script as John and Paco, played by Kris Kristofferson and Donnie Fritts. In a scene filled with sexual tension and totally improvised, the bikers get the drop on Bennie. John then forces Elita to accompany him off into the rocks intent on raping her. Overwhelmed by a sense of helpless rage, Bennie calls after John, swearing he’ll kill him. But Elita turns back saying: “No, you won’t, Bennie. I’ve been here before, and you don’t know the way.”

In the screenplay, John’s violent rape of Elita can be heard taking place off screen. But in shooting the scene, Peckinpah again takes things in an unexpected direction. Away from the campsite, John stops and using a switchblade, tears open Elita’s blouse, exposing her breasts. Refusing to be dominated, she slaps his face hard, then does it again. When he then hits her back, she defiantly refuses to give in to tears. Denied the ability to subdue her with violence, John backs off. Brooding, he walks a short distance away, takes out his gun and sits down against the rocks considering what to do.

Paco (Kris Kristofferson) and Elita (Isela Vega)

Sensing that unless she acts, John will turn his anger and frustration on Bennie, Elita becomes the sexual aggressor. Moving to him, she drops down before him and whispers: “Please don’t… please.” Then reaching out, she takes his face in her hands, drawing him into a kiss. At the same time, overpowering the other biker, Bennie grabs his gun and races to her rescue only to discover not rape but what appears to be the prelude to lovemaking. Enraged and confused, he kills both John, then his partner as he comes rushing up. Shaken by the intense emotions of these events, Elita runs to Bennie who holds her. Then turning, he leads her back to their car, and they drive away.

Playing against all of our preconceived notions, Peckinpah has turned a predictable rape scene as originally written in the screenplay completely upside-down. Instead of a helpless woman being violated who must be rescued by the man who loves her, it is the woman who rescues herself. Bennie’s subsequent actions – killing the bikers – have nothing to do with saving her, but everything to do with salving his own male ego. By portraying it this way, Peckinpah exposes rape as a crime of violence, not sexual gratification. From the moment rape seems inevitable, it is Elita who is in charge. For her, sex is not love. It is simply an act to be endured as a means of protecting the man she loves.

Consistently throughout Alfredo Garcia, Peckinpah underscores this lesson. The men may think they are in control, but without question it is the women who drive every key story point. Opening with El Jefe’s daughter’s refusal to submit to her father’s will, Peckinpah sets the story in motion. It is Elita who knows where Alfredo is buried and reluctantly takes Bennie there against her better judgment. It is Alfredo’s grandmother’s relentless obsession to retrieve and return the severed head that results in the senseless massacre of her family. And in the end, as Bennie holds El Jefe at gunpoint, it is his daughter who commands: “Kill him…!” Throughout the film, the women act while the men react. The depth and complexity of this revelation runs counter to the common assumption that Peckinpah’s work is simply a reflection of unfettered machismo. For Sam Peckinpah, nothing is simple.

Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974)

Let us now turn to the darkest and most disturbing point in the film: when Bennie wakes to find himself buried alive in Alfredo’s grave with Elita’s lifeless body there beside him. It is at this moment that Oates’s performance transcends every expectation. Allowing himself to be completely buried, his clothes covered in blood and grime, dirt in his hair, his ears, his mouth, Oates delivers an astonishing transformation as he fully gives himself to Peckinpah’s vision. A man now lost and beyond salvation, Bennie learns too late that he has failed to cherish and protect the one person in his life who really loved him. A sense of tragedy pervades the scene. “Like the base Indian, threw a pearl away. Richer than all his tribe…”

Bennie has nowhere to turn and no hope of redemption. And so begins a strange black comic odyssey as he takes the only course he left open to him – to recover Alfredo’s head and return it while making those responsible for Elita’s senseless death pay. In doing this, of course, Bennie must confront his own culpability. Thus his journey becomes one of existential self-discovery and destruction.

When Sam Peckinpah had first given me the screenplay for Alfredo to read that first week in Mexico City, this was the ending:

EXT. HACIENDA ENTRANCE – DAY

THE CAR SLIDES ONTO THE MAIN HIGHWAY – finally regains control and speeds away.

INT. CARLOS’S TAXI – DAY

BENNIE SINKS BACK INTO THE SEAT – looks down at the bulging flight bag – pats it.

BENNIE:

Relax, Al… we’re going home.

EXT. HIGHWAY – DAY

AND THE CAR CARRIES HIM OFF DOWN THE HIGHWAY WITH ALL OF THE MARBLES BUT ONE – The only one that really mattered. As the car gets smaller and smaller… FADE OUT.

The next day when we met, Peckinpah had asked me what I thought. Candidly, I said that I felt it was a potentially powerful story, but the ending had two problems. First, Bennie should not have a getaway driver (Carlos in the script) – it is his quest and he needs to finish it alone. And second, he lives.

Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974)

Weighing my objections, Peckinpah shook his head. “That’s because he’s a survivor,” he countered. “And exactly what is he surviving for?” I asked. “The one person who really mattered is dead. What’s he escaping to?” “Interesting,” he replied gruffly, then turned to the business of the day.

Clearly, though, our discussion that day resonated somewhere in Peckinpah’s subconscious mind. Because four months later, when he actually committed it to film, he changed the ending as Bennie completes his revenge then dies alone in hail of bullets: an existential choice made by a man with nowhere left to go.

~

One final observation. It’s been said that great artists are both selfless and selfish. They compulsively steal time from those they love and give it to their art. Like Bennie, blind to how much Elita matters to him until it is too late, Sam Peckinpah throughout his life intentionally sabotaged every important relationship in the name of what mattered to him most: his films.

On Tuesday 11 December 1973, Peckinpah completed shooting the complicated sequence that takes place along the rural road where Sappensly and Quill brutally murder the Moreno family and in turn are dispatched by Bennie. The following day the company would travel to its final location, the Hacienda de San Juan north of Mexico City, not far from the pyramids of Teotihuacan.

Garner Simmons, his wife Sheila and stuntman Whitey Hughes on location on Alfredo Garcia

Credit: Garner Simmons

Since it would provide us an uninterrupted time to talk, Peckinpah suggested I join him in his trailer for the move. And so we spent that night drinking and discussing his life, his films and filmmaking in general as he candidly answered every question I posed. We arrived at the Hacienda a little before midnight. In the background of the audio tapes I made at the time, it is possible to hear the constant chanting of the pilgrims as they make their way to the nearby Basilica of the Virgin of Guadalupe. A strange eerie mix of pagan and Catholic rituals. As a sign of devotion, many make the journey literally on their knees in hope of a miracle. It was dawn by the time they finally stopped. And so did we.

By week’s end, Peckinpah had completed the scenes for what would be the opening of the film – the discovery of the girl’s pregnancy and her father’s command that they find Alfredo and bring him his head. Having been cast as one of El Jefe’s bodyguards, I was given the opportunity to observe Peckinpah at work firsthand. It was an invaluable experience. He had also cast my wife, Sheila, who had flown down from Chicago, as one of the ladies in waiting. Taking Sunday off, he began preparing for what is perhaps the film’s most complicated sequence: Bennie’s confrontation with El Jefe and the final shootout.

Around six that evening, Peckinpah’s assistant Katy Haber came up to say that Sam would like Sheila and I to join him for dinner and drinks in his trailer. His ex-wife, Begonia Palacios, had arrived from Mexico City, brought out by her brother, Juan Jose, who also happened to be Peckinpah’s personal driver. Having prematurely given birth to their daughter and only child Lupita in October, Begonia had spent several weeks recuperating as Sam’s guest in the home he was renting in the Zona Rosa in Mexico City. But once the baby had been discharged from the hospital, Begonia had taken her and gone to live with her mother. Since Sheila and I were the only other couple on location, Sam’s invitation made sense. We obviously accepted.

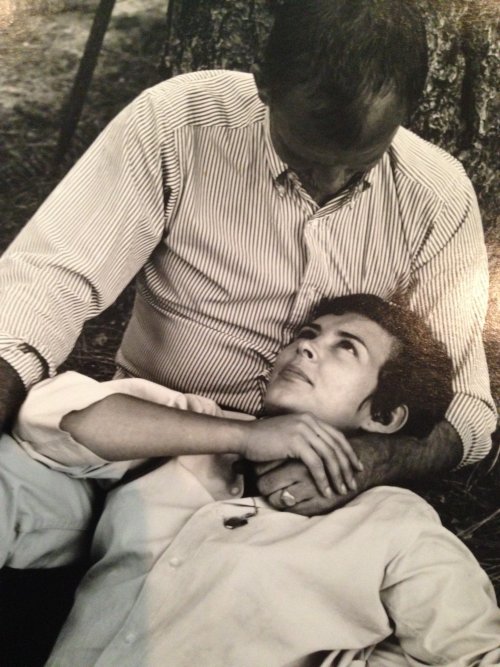

Sam and Begonia Peckinpah in happier times (circa 1967)

Credit: Garner Simmons

Petite and radiant, Begonia was charmingly animated. And as the evening made its way towards midnight it became clear that she was attempting to invite both herself and their baby back into Sam’s life. As he had been with the actresses in the casting session, Sam was both courtly and flirtatious, telling stories of how they’d met while shooting Major Dundee, and how he’d married her and the time they’d spent in Europe as Sam was trying to resurrect his career after the short-lived debacle of The Cincinnati Kid.

Between the laughter and Mexican brandy, Begonia picked her moment and suggested to Sam that she not return to Mexico City but stay there with him. They could even send for the baby. Be a family again. Clearly she wanted to rekindle their relationship.

Listening to her, Sam became very quiet as Begonia continued to press her case. And then in an instant, Sam’s mood completely changed as he turned on her, his voice filled with a dark cryptic edge. In a heartbeat, she knew she had crossed a line as Sam summoned Juan Jose and ordered him to drive her back to town, and never bring her back.

Later, after they had left and we were alone finishing off what was left of the brandy, Sam looked at me and said: “You understand…? Why I had to do it…? The film comes first. Nothing else matters.” And the next morning in his trailer, Katy Haber took charge of his day, making certain that Sam was in control of the one thing in his life that mattered most: the film he was making.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.