Peter Watkins is a filmmaking hero and his masterpiece Edvard Munch is my favourite movie. These two things have been the case since my professor and Watkins expert (and friend) Dr. Joseph Gomez introduced me to his work when I was an undergraduate at North Carolina State University in the late 1990s. Watkins’ Munch film is a kaleidoscopic, profoundly expressionistic, semi-nonfiction historical bio-pic that does truly radical things with sound and image. The film has influenced me greatly and I return to it regularly, like an old friend. This seems somehow appropriate considering how personal the film was to Watkins – its once beloved, long-since-exiled creator.

On occasion of the new Masters of Cinema Blu-ray release of the 221-minute ‘long version’ of Edvard Munch, I talked over email with Gomez (who also supplied some writing for the release) about this movie and the man we both admire so much.

You’ve always talked about how Peter Watkins felt like an outsider and how he came to identify deeply with Edvard Munch, the human being. For a filmmaker that was, as I understand, a kind of ‘superstar’ at the BBC in his twenties, Peter came to feel deeply alienated from his peers and the business, in general, which helped push him to make Edvard Munch. How did he get there?

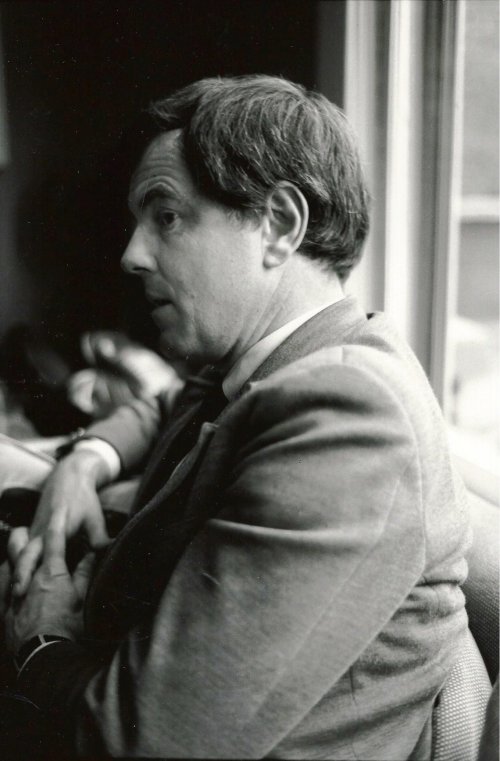

Peter Watkins in the 1980s

After making Culloden (1964), Peter joined Ken Russell as a young BBC superstar, but after the BBC refused to telecast The War Game in 1965, Watkins resigned. However, he did not ‘go gentle into that good night’. Rather, in un-British fashion, he complained loudly and publicly that his film had been banned for political reasons. Some of his former BBC colleagues supported him, but a much larger number personally attacked him for having made the film.

Privilege (1967), his first feature, was, according to critic Penelope Gilliatt, a “brilliant” one that asked the kinds of question that politicians should but never do.

Still, in addition to depicting an Orwellian future for Great Britain, the film was also a very personal one. Watkins clearly identified with the situation of protagonist Steven Shorter, who became a kind of metaphor for his own suppression by the BBC. The film was not well received critically and was deemed un-Christian by a key executive at Rank, who kept it from getting general circuit bookings. As a result, in 1968, Watkins began an exile which has lasted to this day.

This is crazy considering The War Game won the Academy Award for Best Documentary – despite being a fictional dramatisation of a future nuclear war. You’d think he’d be celebrated as an innovator. How did this self-imposed exile result in him making Edvard Munch?

To make films, he journeyed from one country to another, and often, especially with Punishment Park (1971), he was forced to travel with the film just to insure that it was seen in non-commercial settings. Organisations such as Norsk Rikskringkasting (NRK) and Sveriges Radio (SR) in Scandinavia supported him in the making of individual films, but no organisation agreed to hire him on a permanent basis.

After Watkins decided to make a film on Edvard Munch and began extensive research, he realised the many touchstones that he had with the painter: childhood insecurities, awkward personal relationships, critical rejection (often in strikingly similar language!) and a lonely, seemingly endless exile in order to make his personal and experimental art. I would also add that both Munch and Watkins, throughout their lives, remained true to themselves in terms of both their artistic vision and personal integrity.

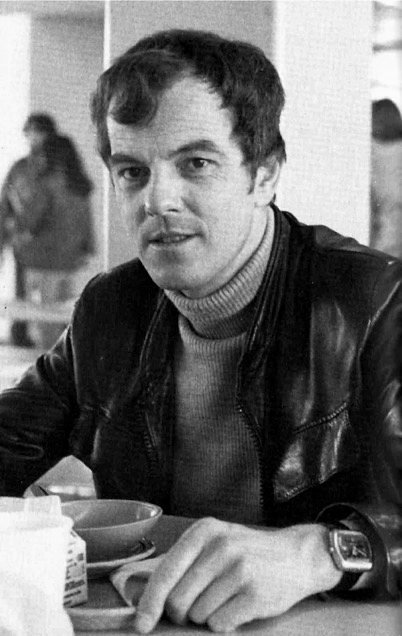

Geir Westby as Edvard Munch

When you showed us Edvard Munch when I was an undergraduate at North Carolina State you screened a 16mm print of the film. This was before it had been released on VHS or DVD, I believe? Was it true that you had the only print of the film in the US? How did you come into possession of that print?

From the mid 1970s to the late 80s, Peter would tour various colleges in the US and screen Punishment Park. I kept his own 16mm print of Punishment Park from the early 70s until the late 90s, and he said that his copy was the only one available anywhere. Most certainly that was the print you saw of Punishment Park in class. When Oliver Groom (of distributor Project X) decided to bring the film out on DVD, a new print was struck from the original negative, which, fortunately, had not been lost after all and was in excellent shape.

When Peter first screened Edvard Munch in the US in the mid-70s he brought a 16mm print of the 210-minute television version, but it had no subtitles, so Peter sat in the projection room with a microphone and spoke the translation of the non-English sections. I believe that version – in this unique format – was only screened at Mohawk Valley Community College, Utica College, and the University of Kansas. Finally, in 1976, New Yorker Films began to distribute the cinema-release version (167 minutes). Peter’s own print of that version was also stored with me, and that was probably the print that you saw at NCSU, but it was not the only one available.

That clears things up, except for the question of the different versions of the film. Why are there so many versions? And do you know how Peter conceived of and executed the different versions and which one he preferred?

Peter first encountered the paintings and drawings of Edvard Munch while screening and discussing The War Game at the Munch Museum in 1968, and it took him six years to complete his film about this Expressionistic artist. There were various tensions between NRK and SR (co-producers of the film) during the shooting and even more after the film was telecast and received a number of superb reviews.

Edvard Munch (1974)

At first, it was unclear whether there even would be a European television release, let alone a cinema release of the film. Finally, with the help of Florence Bodin, Peter got SR to support a 35mm cinema release, somewhere between two and two-and-a-quarter hours. He knew, however, when he started working on this new version that his cut would be considerably longer than that.

Weren’t you actually in the editing room with him at some point?

In the summer of 1975, I spent two weeks in Stockholm with Peter, frequently in a windowless, cramped, stuffy editing room, where temperatures soared to extraordinary heights (it was the hottest summer in Sweden in over a hundred years). Peter knew that the cinema version would have its own rhythm and its own uniqueness, and I don’t think that he approached the editing process as one in which he had to eliminate sections from the long version. Rather, he saw each version as having its own integrity, and often he worked hard at removing a few frames of film instead of cutting out entire shots. Once he did that, however, he then reworked the film’s complex sound patterns and remixed up to four tracks of sound. It was a long and tedious process which, trusting his intuition, he did entirely himself.

During one editing session, he indicated that he was doing this not just to get the film released in cinemas, but because he felt he could further advance the film. As he said then, “It means that somebody seeing the cinema version as opposed to the television version will get slightly different things out of it at times: slightly more emphasis… or slightly less. But this is such a complex subject that it doesn’t matter. I mean who is to say that one is better than the other? There are so many issues and tangents and sub-tangents.”

I watch the film every few months and I recently decided that I absolutely prefer the theatrical cut. To me it has an energy and sense of expression that the longer cut loses, if only just a bit. How about you?

Over the past 40 years, I have gone back and forth with my preferred version. There is a faster rhythm to the cinema-release print and more of a dramatic flow, especially in the first section of the film.

Gro Fraas as Fru Heiberg

Still, the long version offers more information to establish social, political, and artistic contexts. The television version has some unnecessary repetition at times, but the final sequence of this version continues to impress me. The metaphorical representation of Munch’s The Dance of Life presents especially effectively editing patterns that provide a fitting climax to the film, and the cinema-release print seems a bit lacking in comparison.

When you were in the editing room with him, did he seem to have a clear plan or was he working more by feel? I’ve always sort of imagined it as him working like we see Munch work in the film: painting, scratching and gauging the canvas until something expressive emerges. What was the experience actually like?

Peter was in a high state of agitation during this period. He was attempting to get a position at SR, and that was not working out. There also were other issues with SR, and he was editing against a deadline (I can’t remember if it was self-imposed or one desired by SR). As I said before, the editing suite was ungodly hot with no air-conditioning.

Still, Peter was living the film and saw much of his own filmmaking methods in the painting techniques and themes of Munch. He came in each day, at least those during the time I was there, and seemed to work and rework the sound and image according to what he would call “his feelings” or what I would describe as his intuitive imagination.

This method began, to some degree with Privilege and The Peace Game (aka The Gladiators, 1969), but reached a peak in Punishment Park, where most of the film was improvised and the editing process took 8 months. In The War Game, everything was tightly controlled – right down to characters’ “uuughs” in the script.

Edvard Munch (1974)

With Edvard Munch, Peter had the journals to know what Munch said, but the director allowed a number of his amateur actors to improvise responses to Munch and when they addressed the camera. There was a loose script to the film, which overlapped sounds and images, and even had quotations from the diaries, but when I was watching him edit, only on very rare occasions did he even bother to look at it.

Also, in one instance, Peter did not take kindly to some of my questions about why he was doing something in a specific way and responded with the following: “The way I work is like the film itself. I’m fusing together all the different levels all the time… Much of this is not conscious, which is why I’m not going to disturb and formalise the process by which I created that, which was very often an entirely subjective experience. I refuse to put that into rule books. I refuse to lay it out so anyone else can analyse it.”

Wow. Regarding those ‘improvised responses’ from the amateur actors, this is where the film might be most influential to my way of thinking about and even making movies. I’ve always considered those moments virtually nonfiction which, along with Peter’s voiceover, operates on another level of reality that is felt as well as understood narratively.

Would you consider those ‘interview’ segments ‘documentary’, in a sense? How do you think Edvard Munch fits into the very modern discussion of so-called ‘hybrid’ cinema?

Over the years, Peter’s films have changed stylistically in various ways, but most obviously in terms of shot length and editing patterns. Also, from the late 70s on, his criticism of the media and its dependence on what he called the ‘monoform’ became central to his filmmaking and to his writing, especially his essays and letters [see his website]. From his amateur films through The War Game, Watkins made films that, while they did not fit conventional documentary definitions, could be and were frequently described as ‘reconstructions’. After those films, classification according to genre becomes more difficult. I don’t think that Peter ever thought specifically in terms of genre, but he knew, from his first days at the BBC, that their linking of ‘objectivity’ with documentary was not his approach.

Edvard Munch (1974)

I think in the early 70s, Peter was still in the process of seeking forms. He had finished writing a massive screenplay, State of the Union, about the American Civil War, but when the opportunity to make the ultra-low budget Punishment Park came about, he discarded the idea of a script and, with a loose outline, gave his amateur actors the opportunity to improvise, or in most cases to speak their political positions through the characters they portrayed.

This experiment was carried over into the making of the far more complicated film on Edvard Munch. In some cases (especially Geir Westby as Munch and Kåre Stormark as Hans Jagger), actors looked strikingly like the historical figures, but often the actors had similar sensibilities to those they were portraying. Thus, when bohemian women from Kristiania speak about how they are ignored or suppressed, the actresses ‘improvising’ are presenting their own attitudes about life in 1970s Oslo.

Watkins’ images often looked like Munch’s paintings, too, of course.

In many ways, as Watkins pointed out, Edvard Munch was about the past and the present, about Munch and about Peter Watkins and, ultimately, about all of us. I doubt if Peter is familiar with Jean-Luc Godard’s statement that “All great fiction films tend toward documentary, just as all great documentaries tend toward fiction,” but I don’t think that he would see the comments, say, of Eli Ryg as Oda Lasson in the film as ‘fiction’. For him, what she says is true to the character and to Eli’s own beliefs.

Peter Watkins

I suspect that Peter would dismiss the term ‘hybrid cinema’ as just another academic term which attempts to pigeon-hole creativity, but clearly Edvard Munch could fit into any discussion of the term. In my post-academic life, I have found that I too tend to use fewer and fewer terms that I once depended upon. Since I do not write many critical essays anymore, I can simply say that I do not care about attempting to classify Edvard Munch as a documentary or as a hybrid genre; I simply consider it one of the great films of the last half of the 20th century – and it gets even better every time I watch it.

I hate the term ‘hybrid’, for what it’s worth. Why do you think so few filmmakers have been able to take the baton, so to speak, from what Peter accomplished with Munch? It’s a film that has birthed very few children, despite its invigorating ambition and formal expansiveness.

Peter’s ideas about the so-called ‘reconstruction’ film may have been influenced, in part, by the old You Are There and the David Wolper Biography TV programmes, but he pushed his methods further than either of these shows did. By the time he is making Edvard Munch, his methods of making films have become immensely complicated, and the risks that he is taking are greater than anything he has ever done before. Although it focuses on just ten years of the artist’s life, the film has political, social, artistic, sexual and historical contexts that flow together, like the many layers of paint on some of Munch’s paintings. Filmmakers such as John Cassavetes have depended on significant improvisation in their films, but with actors, not with amateurs who, in Watkins’ films, are often expressing their own beliefs.

Finally, Watkins wants to create new relationships with his audience and to make them question the ‘nature of truth’ and the entire form of the documentary. Some of this is only implicit in the Munch film, but it becomes explicit in both The Freethinker and La Commune.

I think about Peter’s work every time I start to embark on a new project, but it’s almost like I know going in that I won’t reach his heights. I’ve always associated the film with you and with learning about the possibilities of cinema. So it has a special place. You’ve told me that Peter might be working on another Munch film? A follow up, of sorts? What can you tell us about that project?

After making Edvard Munch, Peter was offered biopic projects from West German Television (Alexander Scriabin) and Italtelevisionfilm (Tommaso Marinetti), but both came to naught: one because of an unstable economic situation and the other because of changes in administrative executives. Watkins then proposed a sequel to the Munch film, but SR was not interested. He was able, however, to salvage his plans to make a film on Strindberg, The Freethinker, largely through the production assistance of high-school students.

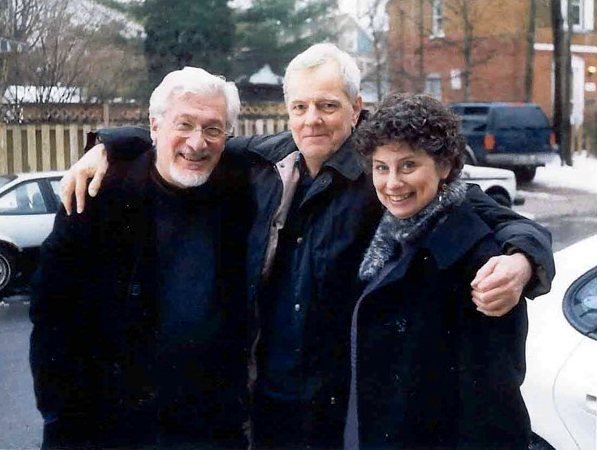

Joseph Gomez (left) with Peter Watkins and Andrea Gomez

Credit: Vida Watkins

Two years ago, after a 40th anniversary reunion party in Oslo for the Munch film, Peter began thinking of a next-to-no-budget film about Munch’s last years. Since then, he has had wonderful co-operation from Munch scholars and from the Munch Museum. Now, at age 80, in a village in France where he and his wife, Vida Urbonavicius, live in a modest house, he works almost every day researching what can only be another personal work about the man with whom he feels such a close kinship.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.