Web exclusive

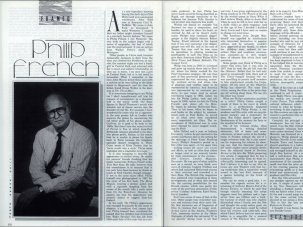

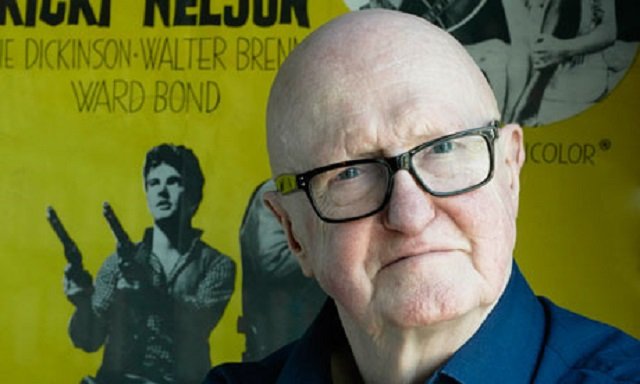

I first got to know Philip French in the mid-1980s, shortly after I’d joined the film section of Time Out. If memory serves, our first encounter was at some lunch given for the press, and he thanked me for a few words I’d written in praise of a season of films about journalists and journalism which he’d programmed for the National Film Theatre (now BFI Southbank). We hit it off immediately, and I was struck not so much by his enormous erudition – with which, as a reader of his books and Observer reviews, I was already very familiar – as by his easy-going warmth and quick sense of humour. Though he was one of the best and most important critics in the UK and I was a mere rookie, I never for a moment felt he was talking down to me; on the contrary, he seemed genuinely interested in my opinions and happy to sit discussing movies with me as long as the restaurant was prepared to tolerate our presence.

I mention this not to make some special claim on his affections (though I’m happy to say that while Philip and I never got to become close friends, we always remained on excellent terms thereafter), but because my experience appears to have been quite typical, as anyone reading other film critics’ responses to Philip’s death will be aware. He was immensely courteous, kind and generous with both his time and his encyclopaedic knowledge. Once, when he heard I was writing a book about the films of Nicholas Ray, he suggested I read a New Yorker article which had been the original inspiration for Ray’s 1956 masterpiece Bigger than Life; entitled Ten Feet Tall, it was an essay about the perilous side-effects of cortisone, and was by one Berton Roueché, who specialised in writing about medical matters. Unsurprisingly, I’d never heard of the writer, but as it happened, Philip had a collection of Roueché’s essays, and insisted on giving it to me. Which aspect of this story is most telling about Philip? His generosity in parting with what was by the late 80s, I presume, a pretty rare volume? Or the very fact that he was not only familiar with the obscure essay in question, but had it in his library? Whatever, I find it very hard to imagine relating such an anecdote about most other people of my acquaintance.

It is all too easy to focus on Philip’s professional brilliance; for instance, when I commissioned him, as one of ten top writers on the cinema, to contribute to a book I was editing called Film: the Critics’ Choice, he typically turned in excellent copy that hadn’t a single error, typo or punctuation mark out of place. But there was of course far more to him than professional expertise and integrity and his famously formidable memory and intellectual acuity; he was immense fun to spend time with.

Many of my own fondest memories are of dinners at the Cannes Film Festival – we used to try to fit in one or two together most years – but perhaps my most vivid recollection from the Croisette is of sitting with him in the enormous Salle Lumière for a special screening of John Ford’s Wagon Master; this was, I think, in 1995. As it transpired, he and the Standard’s Alexander Walker were there partly to receive some kind of special award to mark the longevity of their attendance at the Festival (each had also served on the main jury, Philip in 1986); but what most thrilled the eternally dedicated moviegoer sitting next to me was not his own gong but the chance to watch the newly restored western while sitting just a few yards away from its now elderly but stylishly Stetsonned stars, Ben Johnson and Harry Carey Jr. Philip, two decades older than I, was then in his early 60s, but as we stood applauding the old timers while they took their bows, I felt almost as if I were in the company of a schoolboy fan who would never ever tire of his beloved westerns.

The last time I saw Philip was in September 2013, on the evening he received his BFI Fellowship. We spoke at some length, and though his slowly but steadily deteriorating health was making it harder for him to get around, he was clearly enjoying himself and determined to make the most of the occasion; in short, he was as dazzlingly bright, in both senses of the word, as when I had first met him.

Thereafter, we communicated occasionally by phone or email, most notably when I invited him to write the brochure notes for a BFI Southbank season of films by Louis Malle, a filmmaker he liked and admired enormously. (His extensive bibliography includes a wonderful book of interviews, Malle on Malle.) He wrote the notes – to perfection, of course – but unfortunately, because of problems with prints, the retrospective had to be cancelled at the last moment. I called Philip to explain the situation and apologise for having wasted his time, adding that we would try to do the season if and when adequate materials became available. Characteristically, he could not have been more understanding, joking that he hoped, despite his health problems, still to be around for the season whenever it eventually took place.

Very sadly, that was not to be. But if ever we are able to do the retrospective, I for one will be arguing that it should be dedicated to Philip’s memory. (And what a memory!) Meanwhile, whenever I watch a good western, or a Malle movie, or Wild Strawberries, I’ll be remembering the many moments I spent with Philip – in person, or simply enjoying his writing.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.