It may be that the current spate of – sometimes grudging – accolades for Jerry Lewis, who died this week, may be the last substantial praise that the comic and director will receive. It has been decades since Lewis, as an active filmmaker, enjoyed the support of illustrious enthusiasts such as Jean-Luc Godard, Robert Benayoun and Luc Moullet (French highbrow regard for Lewis has often been considered a prize joke in the US), although in recent years, his work has still been subject to scholarly critical discussion in studies by Chris Fujiwara and Frank Krutnik.

But it’s easy for admirers to feel defensive. The problem is partly that, even in the best of Lewis’s films, his gags – as seen today – often come off as brilliant, rather than actually raising laughs. That’s a matter of changing taste, and if Lewis’s humour and persona were of their time, they nevertheless absolutely defined a predominant comic mood of that time, the American 50s and early 60s. If Mad Men’s Don Draper had ever found an afternoon to take his kids to a movie, it would have been one of Lewis’s comedies; they would have loved it, he’d have looked on with pained tolerance (but probably recycled one of the gags for an advert).

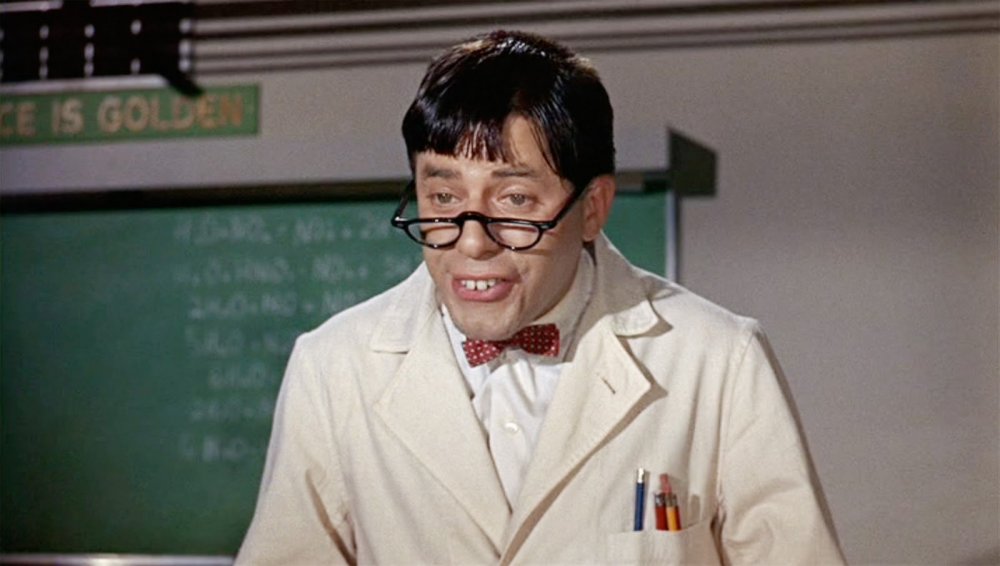

Jerry Lewis in The Nutty Professor (1963)

It’s hard today to feel entirely comfortable watching Lewis’s patented persona, the gawky, twitchy, childlike idiot – still the enduring template for the American ‘nerd’ archetype. But what is remarkable is what Lewis did with that persona, and how it changed over the years. His most celebrated film remains 1963’s Jekyll-and-Hyde comedy, The Nutty Professor, in which lovably goofy boffin Dr Julius Kelp transforms himself into glamorous but loathsome smoothie Buddy Love (generally regarded, despite the comic’s denials, as a cruel lampoon of his former stage and film partner Dean Martin). In later Lewis films, a version of the dapperly groomed, oddly cold, Buddy persona would increasingly dominate, as Lewis insistently projected the notion of his mastery and control – as in the self-aggrandising title of his 1971 book The Total Film-Maker, a considered résumé of his thoughts on comedy and the craft of cinema. One famous example of that craft was Lewis’s pioneering of the now-standard technology of video assist in order to direct his own performances on set.

Lewis had the archetypal ‘born in a trunk’ showbiz childhood. Born in Newark, New Jersey in 1926 to entertainers Daniel and Rae Levitch, he grew up as Joseph Levitch – although biographer Shawn Levy has pointed out that his birth certificate carries the name Jerome. Becoming part of their act at an early age, he rapidly became a fixture at hotels on the so-called Borscht Belt of the Catskill Mountains; in his teens, he performed solo. His breakthrough came when he met crooner Dean Martin, and in 1946 formed a massively successful comedy and cabaret duo. Based on Lewis’s gangling child-like hyperactivity and Martin’s leisurely sophistication, it was a combination that Lewis defined as “a handsome man and a monkey”. This unsettlingly self-deprecating formula might seem implicitly to invoke the antisemitic rhetoric of which Lewis must certainly have been a target in his time, but in a New York Times article this week, Jeremy Dauber has persuasively argued that the contradictions of American Jewish identity were something that Lewis consistently explored to great effect in his work.

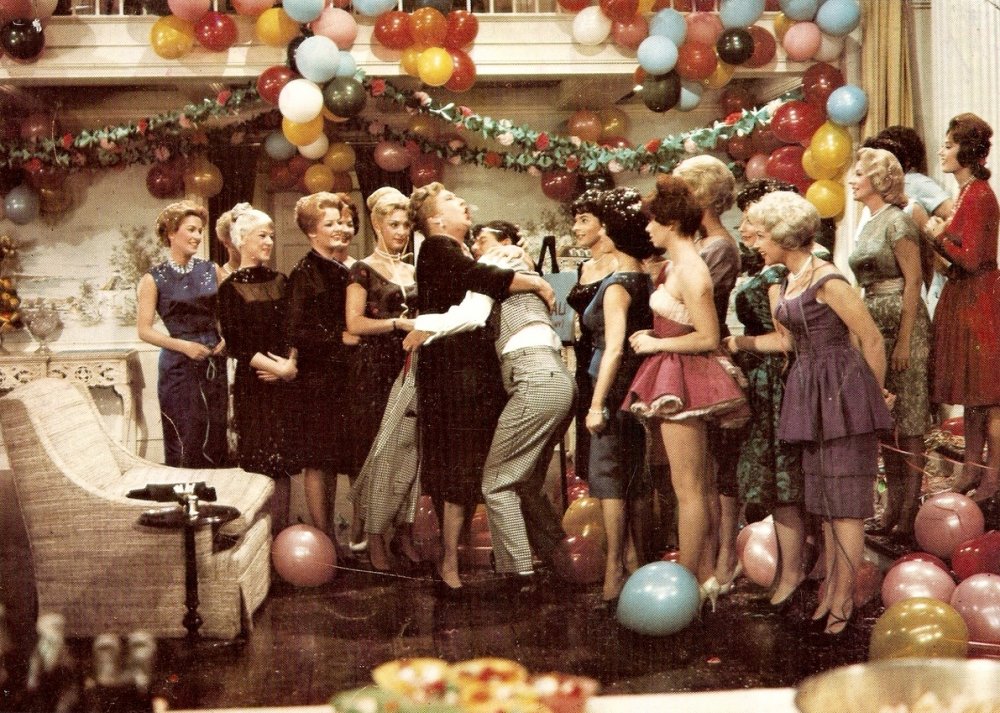

Lewis with Dean Martin in Artists and Models (1955)

Having conquered stage and TV in the late 40s, Lewis and Martin were brought to Hollywood by producer Hal Wallis, making their screen debut My Friend Irma (1949). Their most celebrated screen work was with director Frank Tashlin (Artists and Models, 1955; Hollywood or Bust, 1956) whose pedigree as an animator made him a perfect candidate to orchestrate Lewis’s cartoonish humour. After the duo’s acrimonious break-up, Tashlin directed Lewis solo vehicles including Cinderfella (1960) and The Disorderly Orderly (1964).

But it was Lewis’s transition to directing that established him as a truly individual force in American screen comedy. His first directing venture, 1960’s The Bellboy, was shot at the Fontainebleau Hotel, Florida, in 26 days immediately after Lewis had completed a live engagement there. Essentially a narrative-free assemblage series of gags photographed in elegant black-and-white by Haskell Boggs (the film is, among other things, an elegant visual essay on early-60s hotel modernism), the film stars Lewis as hapless, yet sometime inspired (and until the very end, silent) bellboy Stanley, observing or triggering a series of surreal incidents. Highly uneven, at the best, the film uses space and the human figure in a way not unlike Jacques Tati (as in the trick-edited sequence where Stanley furnishes a cavernous ballroom with tables in seconds flat); the film also comes across as a brash but acute satire, in the manner of Mad Magazine, of the American capitalist way of leisure.

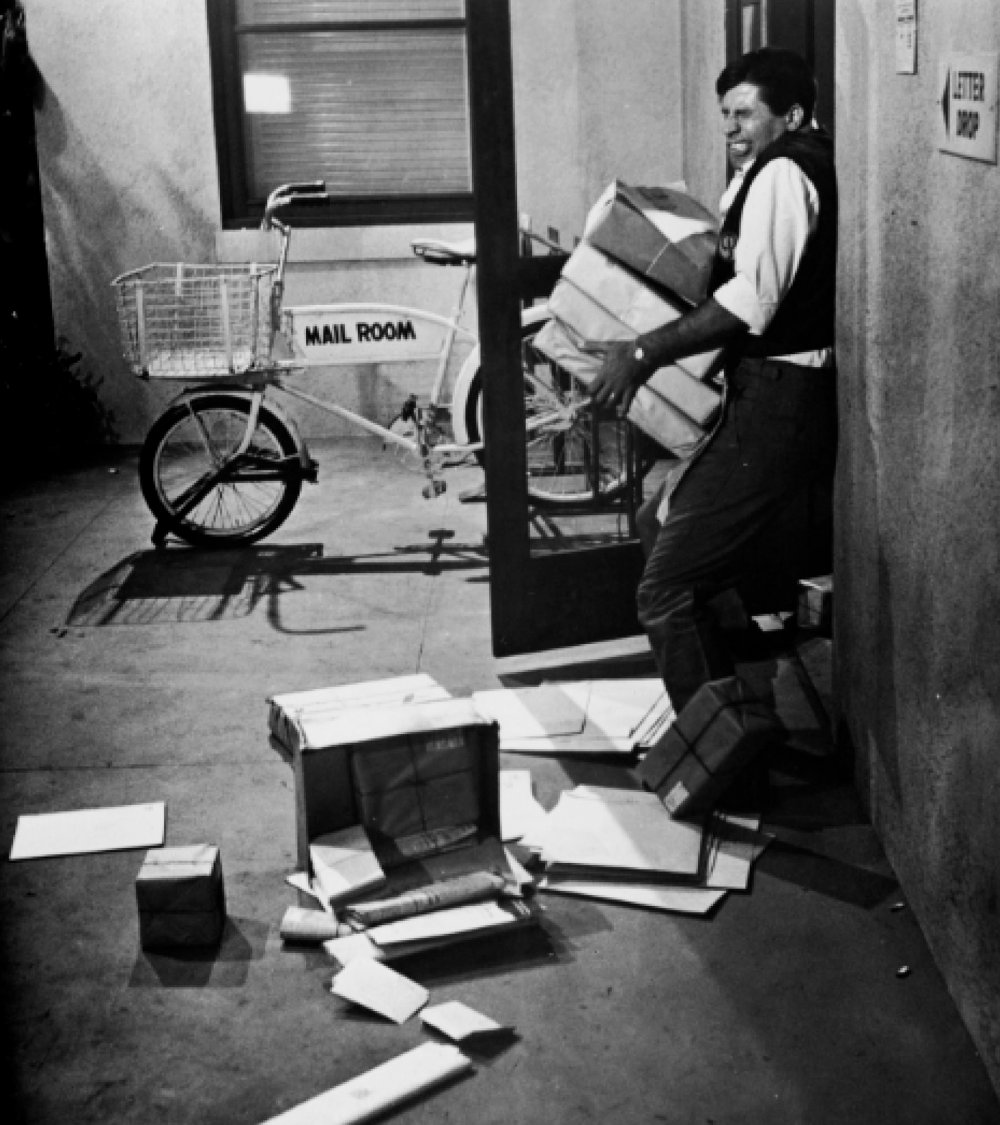

Lewis in The Errand Boy (1963)

The Bellboy also introduced a self-reflexive streak that became a Lewis trademark, with ‘Jerry Lewis’ appearing as a character (and with ‘Joseph Levitch’ listed in the opening credits) as a neurotic, baffled celebrity attended by a bustling host of sycophantic minions. He would repeatedly play on the split identity theme, not just in The Nutty Professor but also in the multiple roles of The Family Jewels (1965) and Three on a Couch (1966) – a trend that lent some plausibility to the Lacanian reading of his work later proposed by critic Serge Daney in Cahiers du Cinéma. His films constantly drew attention to themselves as artificial products of the showbiz machine, notably his comedies about the mechanics of star-making in film (The Errand Boy, 1963) and pop (The Patsy, 1964). His self-directed work reveled in artifice and, in The Ladies’ Man (1961), in the splendour of mise en scène: that film contained surreally balletic dance sequences and an elaborate ‘doll’s house’ set that spawned knowing echoes in Godard’s Tout va bien (1971) and Julien Temple’s Absolute Beginners (1986).

Lewis in The Ladies’ Man (1961)

But Lewis’s directing career saw him moving further away from public favour. Later films Hardly Working (1979) and Smorgasbord (1981) were significant to French critics, but barely to audiences. Most notoriously, Lewis made the abortive The Day the Clown Cried (1972), a comedy about a clown in a German concentration camp; the film remains unreleased, and a holy grail to connoisseurs of what may or may not be truly unwatchable. Curiosity about the film has been fueled by years of speculation – and in recent years, teasing comments by Lewis – as well as recent footage showing Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin visiting the set. Can Lewis’s film really be the unforgivable lapse of taste that rumour has deemed it, or was it perhaps an audacious attempt to confront painful questions about inhumanity and the consoling power of comedy? Did Lewis simply attempt to go where Roberto Benigni would later venture, to near-universal acclaim, in Life is Beautiful (1997)? Certainly, Jean-Michel Frodon, one of the few critics to have seen a version of it, recently called it “a very interesting and important film”, comparing it favourably to Schindler’s List (1993).

As with so many screen comics, Lewis ended up being eclipsed by his own trademark – a cartoon of his laughing profile became the logo for Jerry Lewis Cinemas, a chain that went bankrupt in 1980 after just over a decade in business. A more enduring activity, starting as early as 1952, was Lewis’s regular hosting of an annual TV telethon to raise funds for muscular dystrophy research – although the tear-jerking sincerity of his presentation of ‘Jerry’s Kids’ became proverbial as a coercively insensitive presentation of disability.

Lewis as talk show host Jerry Langford in The King of Comedy (1983) with Robert De Niro

That the once insouciant young clown might have become solemn, introverted or even embittered patriarch was brought home by Lewis’s casting as TV host Jerry Langford in Martin Scorsese’s 1983 The King of Comedy (a role originally intended for real-life compere Johnny Carson). As the solitary Langford, dealing with the unwanted attention of Robert De Niro’s would-be acolyte and Sandra Bernhard’s deranged superfan, Lewis gives one of the great ‘lonely at the top’ performances, all the more affecting because a) he doesn’t attempt to be remotely ingratiating or win our favour, and b) because it seemed perfectly plausible that he was essentially playing himself.

A similarly self-reflexive part came in 1995, in Peter Chelsom’s eccentric Funny Bones, with Lewis as George Fawkes, a revered comedy star who insisted that you were either born with funny bones or you weren’t. It was revealing that at the end of the film, George turns out to have stolen an essential part of his shtick from a Blackpool end-of-the-pier act; Lewis himself never made a secret of his debt to Chaplin, Keaton and especially Stan Laurel (the subject of several surreal cameos in The Bellboy, where he’s impersonated by Bill Richmond). There was also an appearance alongside Johnny Depp and Faye Dunaway in Emir Kusturica’s awkwardly surreal Arizona Dream (1993) in which, although playing a car magnate, Lewis again essentially appears as a sort of ‘objet trouvé’ resembling himself. His last lead role, as an elderly jazz pianist in Max Rose (Daniel Noah, 2013), received a lukewarm thumbs-down when it premiered in Cannes; other late credits include playing Nicolas Cage’s father in thriller The Trust (2016), and (probably one for the obsessive completist) a cameo as ‘Bellboy’ in Brazilian comedy Till Luck Do Us Part 2 (2013).

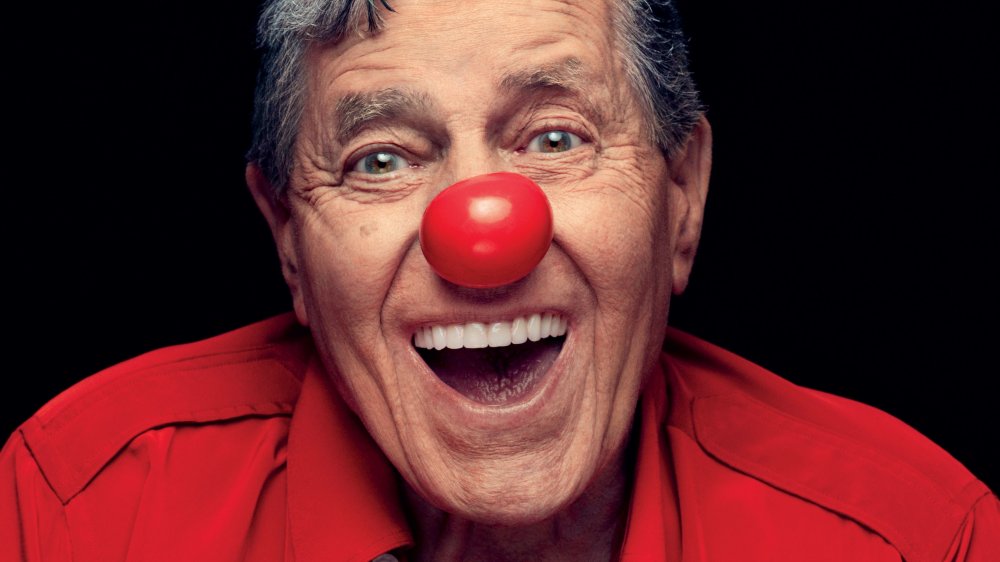

Jerry Lewis

Lewis’s last genuine triumph, however, was a magisterial Broadway debut in 1995, playing Lucifer figure Mr Applegate in a revival of the musical Damn Yankees (he had previously been involved in an ill-fated mid-70s attempt at the 30s revue Hellzapoppin’). Damn Yankees saw him hoofing alongside Broadway star Charlotte d’Amboise and replaying various phases of his ever-changing persona to a rapturous audience – some of whom may have remembered the ‘monkey’ from his heyday, but all of whom clearly knew which nostalgia button Lewis was pressing when he donned a firefighter’s helmet, went cross-eyed and whined, “Hey, lay-deeee … ”

It remains to be seen whether Lewis will mean much to future generations, or be considered anything other than the father figure to later generations of American comedians. Notwithstanding Eddie Murphy’s affable genial restyling of The Nutty Professor, it would be a terrible shame if Lewis were remembered as the true progenitor of Adam Sandler. Either way, there will always be critics to insist that Lewis, whether or not you care for his humour, had a coherent auteur identity, both as star and director – that there exists not just “Lewisian time” and “Lewisian space” (Fujiwara) but, in the formulation of Serge Daney, a full-blown, unmistakable “monde lewisien”.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.