Web exclusive

Francesco Rosi

The past week’s terrorist murders in France have strengthened the belief that artists should always be free to ask uncomfortable questions of those with power. Few filmmakers felt this more keenly than Naples-born Francesco Rosi, whose career was characterised above all by rigorous socio-political engagement.

Rosi’s father worked in the shipping industry but was also a cartoonist who at one time had fallen foul of the authorities for his satirical drawings of Mussolini and King Vittorio Emmanuele III. The young Rosi followed in his father’s footsteps and by the end of World War II was working as an illustrator for children’s books. He contributed to the local newspaper Sud and radio station Radio Napoli before leaving Naples for Milan in late 1946 where he spent a short period working for another newspaper, Milano Sera.

He soon found himself in Rome where fellow Neapolitan Ettore Giannini invited him to collaborate on a theatrical production of Salvatore Di Giacomo’s O Voto. Rosi not only served as Giannini’s assistant, he also took on an acting role and designed the playbill.

After this experience in the theatre, Rosi planned to apply for Italy’s prestigious Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia film school, but his entry into the world of film was expedited when a mutual friend introduced him to the director Luchino Visconti, who was about to embark on his second feature, La Terra Trema (1948). Chronicling the lives of a family of Sicilian fishermen, the project was a major undertaking. Not only was it to be shot on location, it would feature non-professional actors speaking in Sicilian dialect.

Rosi worked as Visconti’s assistant (alongside Franco Zeffirelli) and also supervised the film’s dubbing into a more widely intelligible Italian. “This first extraordinary experience allowed me to enter the world of film through the front door,” he told Aldo Tassone in 1979. Visconti “took a Verghian nineteenth-century structure [Giovanni Verga’s 1881 novel The House by the Medlar Tree] and made it his own. I believe that my experience with Visconti on La Terra Trema was fundamental to my way of working.”

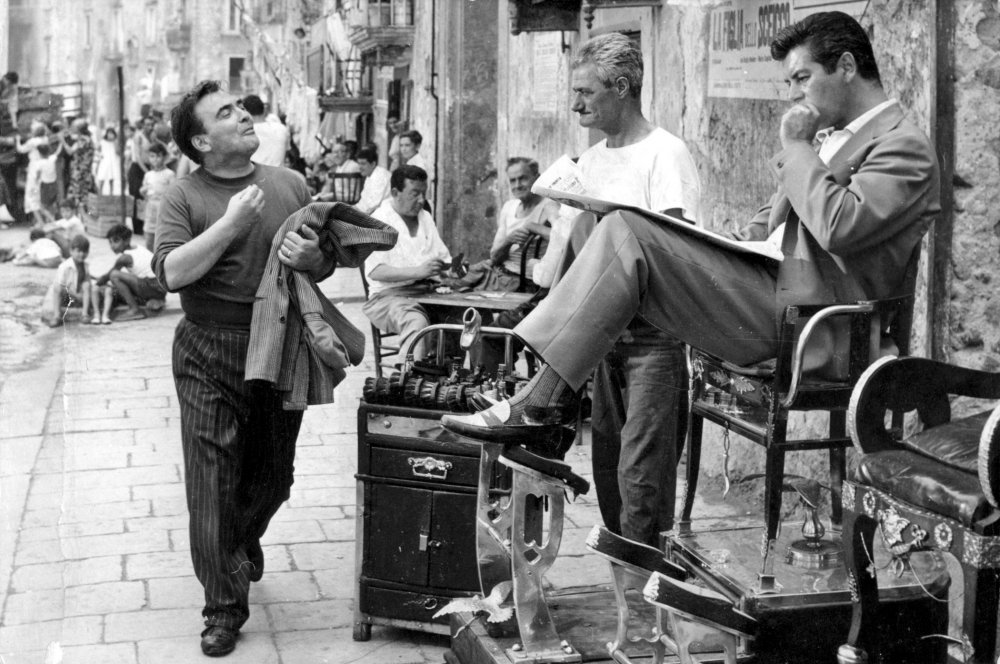

The Challenge (La Sfida, 1958)

Rosi’s collaboration with the Milanese director continued into the 1950s, on films as diverse as Bellissima (1951) and Senso (1954), but he also worked with Luciano Emmer (A Sunday in August, 1950), Raffaello Matarazzo (Torment and Nobody’s Children, both 1951), Michelangelo Antonioni (I Vinti, 1952) and Mario Monicelli (Proibito, 1955) before making his own feature debut with 1958’s The Challenge. Based on the life of Neapolitan gangster Pasquale Simonetti (aka Pascalone ’e Nola), the film drew heavily on the post-war American realism of directors such as Jules Dassin (The Naked City, Thieves Highway) and Elia Kazan (Panic in the Streets) as well as lessons learned during his apprenticeship with Visconti.

The Challenge was the first time Rosi addressed issues of the Italian South and he would return to the meridione for several of his best works. “I’m a man of the South with certain Northern characteristics,” the director remarked in the 1979 Tassone interview. “The choice of themes for my films reflects above all else my fundamental desire to rationalise, to gain knowledge [of a particular subject].”

Salvatore Giuliano (1962)

After 1959’s I Magliari – about a group of Italian workers living in Germany – Rosi made two of his most celebrated film d’inchiesta (cine-investigations). Although Salvatore Giuliano (1962) bore the name of the infamous Sicilian bandit (born just 24 hours after Rosi), it was by no means a traditional biopic. Giuliano is absent for most of the film and Rosi instead explores the forces on both sides of the law that made possible Giuliano’s bloody seven-year reign on the island. “I’ve always thought that if you want to look at problems and their dynamics in the social, economic and political context of a country, one of the ways is to look at characters that have represented that particular world, those that have actually determined it, or maybe they have been expelled from it,” the director told Tassone.

Rosi moved to the Italian mainland for his next picture, remaining in the meridione to address the problem of high-level corruption in Naples. The film featured American actor Rod Steiger as a property developer with political ambitions, but Hands Over the City (1963), like Salvatore Giuliano, is less a psychological study of one particular character and more an examination of the wider forces at play. Rosi would use a similar approach in The Mattei Affair (1972) and Lucky Luciano (1973) – both featuring regular collaborator Gian-Maria Volontè.

Rosi made historical films (More than a Miracle, 1967), war pictures (Many Wars Ago, 1970; The Truce, 1996) and family dramas (Three Brothers, 1980) in a directorial career that spanned almost four decades, but he will be remembered above all as the master of the ‘cine-investigation’ and an influence on several generations of artists, including the likes of Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Roberto Saviano and Paolo Sorrentino.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.