Web exclusive

James Bond tours Istanbul in Skyfall (2012)

In politics, as in cinema, representation is everything. In Istanbul’s Gezi Park, where thousands of protestors spent the first week of June trying to save a public park from destruction, this was also the case. During the protests Gezi resembled a film set. People on their way to the park dressed up for the occasion. They wore gas masks, goggles, Guy Fawkes masks. On YouTube I watched the video of a protestor in full Darth Vader costume. He marched forward with a flag at hand. Some conspiracy theorists said the events were orchestrated by a single mind, as if a film director was behind all that had happened. To me this sounded like a version of the auteur theory.

Scenes around Taksim Square were frequently violent. They were also cinematic, albeit hard to see because of the media blackout. Images posted on Twitter showed trucks and cranes making their way to the Prime Minister’s offices. The violence produced sublime images: a massive fog of tear gas; burning trees glowing in the dark; buses set aflame.

For some protestors at the beginning it was all pretense. They have acted out their roles and returned home afterwards. The events provided them with an opportunity to represent their reality, their essence the way they wanted. The result was very different from the representation offered by news bulletins and films.

The Turkish Film Critics Association was quick to draw a parallel between the events and their beloved art form. The headline of their press release was ecstatic: “We love this film that we’re in!” Critics are used to spending long hours in dimmed cinemas; now they were happy to hit the road and support the protestors. “We are not just the spectators here, we act together,” their statement read. “We take part in and fully support the process that has begun with the struggle for the historic Emek theatre.”

For Turkey’s film community, Emek was much more than a theatre. One can argue that protests began a month earlier when people marched on the street to save Emek. People objected to its transformation into a shopping mall. But their message went unheard. The theatre was demolished in May, a week before the events in Gezi begun.

Authorities responsible for those demolitions said their actions were legitimate: they took their legitimacy from existing laws. Film critics said it was the actions of the protesters that were legitimate: they took their legitimacy from films. “We know this to be the absolute reality, even if only from the history of cinema,” they argued.

Film history offers no absolute realities and Istanbul’s image in that history has changed frequently over the years. Contemporary directors like Nuri Bilge Ceylan and Zeki Demirkubuz make extremely personal films set in Istanbul. But those are often received with indifference among audiences. The arthouse audience is 50,000-strong, even for films that win major awards at European festivals.

There is another strain of filmmaking: more popular Turkish films set in Istanbul. Their directors do better at the box office but critics don’t like them as much. Those films portray the city as a paradise, focusing on the lives of the privileged. Popular columnists who had made a habit of urging arthouse directors to make more accessible films enjoy the happy-go-lucky aesthetics of those films. They accuse film critics of being elitist socialists out of touch with society.

For those who enjoy Hollywood films more than European ones, Turkey had become an interesting place. Big-budget films like Skyfall or Argo not only did well at the Turkish box-office, they were partly made here, with many of their scenes shot on location in Istanbul.

The local media coverage of their productions creates big buzz. More than 600,000 people saw Skyfall in Turkish cinemas since its release last November; dozens worked on its shoot in Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar, where Sam Mendes set its opening sequence.

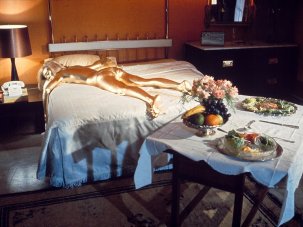

Tatiana Romanova (Daniela Bianchi) traipses Istanbul in From Russia with Love (1963)

Walking around Gezi Park last week, the contrast with the Bond films’ touristic image of Istanbul was stark. I remembered how Sean Connery in From Russia with Love, made 50 years ago, had also visited the Grand Bazaar, the Spice Market and other popular sights. He was courted by belly dancers before taking refuge in the Basilica Cistern. His journey in Istanbul was touristic from beginning to end.

Setting aside the belly dancers, Mendes’s film was comparable to its orientalist ancestor, though its cars are faster and the chase scenes more aggressively edited. The film was applauded in the multiplex where I saw it but there was some criticism in the press of Istanbul’s depiction as an oriental city.

It is not only the critics who are interested in Istanbul’s representation. The city had become an attractive filming location for a number of British and American producers. A group of local film crews are taking advantage of the opportunities on offer. Ben Affleck’s Argo, which overshadowed Skyfall with its Oscar success, is a case in point. Most of Argo’s scenes were shot in Karaköy, the centre of Istanbul’s touristic attractions, a few minutes walk from my apartment and about a kilometre away from the filming location of another British film, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.

Unlike the John le Carré adaptation, where the city poses as its historic self, Argo is part of a new genre where Istanbul masquerades as a different city. During the shooting of The Two Faces of January, a new Patricia Highsmith adaptation due out later this year, a Turkish journalist asked the film’s location manager if “Istanbul would pose as Tehran?” No, came the reply. This time it would become Greece.

“Turkey’s varied looks allow it to double for most Mediterranean and Eastern countries,” said Alex Sutherland, the line producer of both films, speaking to The Location Guide website back in 2011. Istanbul is morphing into other spaces not only geographically but chronologically as well. Sutherland said 2013’s Istanbul is ideal to shoot scenes taking place in the 1960s and 70s.

His is not the only company that takes advantage of this new filmic trend. The line producers of Skyfall worked for Anka Film, which also line produced the 1999 Bond instalment The World Is Not Enough. Sutherland’s venture, Az Celtic Films, is more prolific. He founded it with his Turkish wife Zeynep Santiroglu in 2010. As well as The Two Faces of January, Argo and Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, Az Celtic’s credits include a number of Channel Four and BBC productions, including Top Gear specials and Andrew Marr’s History of the World. His crews are currently producing Our Men, BBC’s new comedy series, starring David Mitchell and Robert Webb. Not surprisingly the series is set in a fictional country (“Tazbekistan”) rather than the city of Bursa, its actual shooting location.

One Sunday evening last February I met Sutherland in Kuşadası, a holiday town on Turkey’s Aegean coast where his crew worked on an adaption of Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio for the German television channel ZDF. The son of the British film producer Muir Sutherland, he had made Turkey his home in 2009. After Argo’s night of triumph at the Oscars he happily announced receiving an email from Ben Affleck about the prospect of shooting another film in Istanbul.

His success is part of a bigger shift in the film industry: in Ankara and Los Angeles ambitious plans about cooperation between Turkish and American filmmakers are being discussed. A few weeks after I met Sutherland, newspapers reported Universal Studios’ plans to build a film studio and theme park in Istanbul. Universal executives and Turkey’s Economy Minister had met in Los Angeles. They plan to christen the facility ‘Hollywood on the Bosphorus’. Universal intends to make an investment of around $3 billion for the new facility.

Oh Beautiful Istanbul (1960)

Although it is an exciting time to work in the film industry in Istanbul, the producers’ interest may quickly shift elsewhere, leaving Turkish crews with illusions perdues. In Kuşadası producers showed me a marionette of Pinocchio’s eponymous hero and said they would get rid of it once the shoot came to an end (during post-production the marionette is be replaced by its CGI-animated double). Looking at Pinocchio’s sad wooden face I was reminded of how appropriate a metaphor it has become for Turkey’s new role as a film set for Hollywood’s latest productions. Istanbul presents itself in many disguises, telling stories that are rarely about its real life.

The events at Gezi Park could be the material for a very interesting film. Although the park currently lacks the discipline of a Mendes or Affleck film set, its energy is inspiring and more exciting than a Bond movie.

Walking around the park last Thursday I came across Senem Aytac, the deputy editor of Altyazi film magazine. I suggested to her that they could edit their new issue at the park. She said it was an interesting idea. She was on her way to a tent pitched by fellow critics. That evening the Turkish Film Critics Association screened a Turkish classic which represents the city in all its glory and sadness. Atif Yilmaz’s film is called Oh Beautiful Istanbul.

And in the June 2013 issue of Sight & Sound

Let battle commence

When developers attempted to demolish Turkey’s oldest cinema, which opened in 1924, it prompted a groundswell of popular protest. By Kaya Genç.