Web exclusive

Tres D (2014)

An international film festival’s national selection is often among its weakest groups of films. Happily, the 16th BAFICI (Buenos Aires International Festival of Independent Cinema), Latin America’s largest film festival with 469 films in this year’s programme, bucked this trend with several good-to-great new Argentine works, each distinct from its peers – and did so even despite substantial budget cuts and the absence of at least three new Argentine films held out in anticipation of higher-profile world premieres.

Buenos Aires International Festival of Independent Cinema

2-13 April 2014 | Argentina

The top prize in the Argentine Official Competition went to Alejo Moguillansky and Fia-Stina Sandlund’s shaggy-dog tale The Gold Bug (made for Copenhagen’s DOX:LAB project), a self-reflexive movie that spins self-bemused circles as it follows members of a film crew conniving a location shoot in order to hunt for buried treasure.

A meatier (and more straightforward) work about cinema proved to be Rosendo Ruiz’s debut feature Tres D, a useful primer to the contemporary Argentine film scene which conducts documentary interviews with several local personalities within the context of a fictional love story that unfolds at a film festival in the province of Córdoba. The agitating filmmaker-critic Nicolás Prividera appears at one point, arms folded and fingers pointing, to explain that there has almost always been a ‘new’ Argentine cinema, and that the national scene has moved from a low period in the 1990s to a current prolific and diverse moment.

The Face (El Rostro, 2014)

One of the working filmmakers he cites is Gustavo Fontán, a focused experimental director who also appears in Tres D explaining his practice in ways relevant to his latest, The Face (El Rostro), also in BAFICI’s national competition. The 53-year-old Fontán propounds a kind of filmmaking that assembles fictional elements “while still holding a conversation with reality,” ideally in seamless union, and gives much to the viewer while leaving “blank spaces in which we find ourselves,” from within which we can reflect upon what we are experiencing.

The largely wordless, oft-elliptical The Face presents a middle-aged man (played by Gustavo Hennekens) and some of his family members as they explore the shores of a clearing by the Paraná River. The black-and-white film shifts between tracking the people in close handheld shots and rendering nature as they might see it. We watch skeletal trees quiver as though responding to visitors, and look out from land onto strong splashes of water, all captured by Fontán and his two cinematographers with a mixture of Super 8 and 16mm film and digital video, the different registers of which are cut together flowingly.

The film’s soundtrack enriches the journey with sharp exaggerations of natural noise. The frame will show a man’s upper body as he walks, while we hear leaves crunching beneath his feet; cows moo, ducks quack and flies buzz while they pass by human figures, or as people wander past them. The Face offers an immersive experience through which viewers can float while feeling tethered to concrete space.

Letter to a Father (2013)

The Argentine competition film Letter to a Father (Carta a un padre) quests at a calmer remove, the better with which its director Edgardo Cozarinsky can view fragments of his life. The 75-year-old author and film essayist has made a longtime practice out of what could be called speculative autobiographies, imagining recent history from a lucidly fictionalised first-person perspective. His great One Man’s War (1982), for instance, details the German writer Ernst Jünger’s experience of World War II through an elegant interweaving of Jünger’s wartime diaries and Occupied-French propaganda newsreel films from the period. His recent trilogy of self-termed “chamber films” that ends with Letter to a Father (the first two films being 2010’s Notes for an Imaginary Biography and 2011’s Nocturnos) assembles people and objects associated with Cozarinsky’s own past, which he contemplates from offscreen.

Letter begins in Entre Ríos, a central province historically home to a population of rural Argentine Jews where the Jewish Cozarinsky’s father grew up, yet a place never visited by Cozarinsky himself, a cultivated world traveller. Initially, the film’s trajectory seems simply that of Cozarinsky finally making that trip and interviewing residents about a parent who died when he was 20 and whose absence he still feels.

The people with whom he speaks, though, come to reverberate with mysterious weight, as do the traces that both father and son have left behind for others in seeming efforts towards self-preservation. A knife that the elder Cozarinsky brought back from a trip to Japan rests in his son’s hands, its engraved inscription left untranslated for fear that the message be banal; the son offers clips from some of his previous films, a ceremonial gesture of unearthing his former selves. “I’ve often wondered what makes us keep things we know are bound to disappear,” Cozarinsky’s Proustian detective of a narrator muses in voiceover. He searches Entre Ríos for an answer, looking outwards in order to learn about himself.

Intervened Events (Sucesos Intervenidos, 2014)

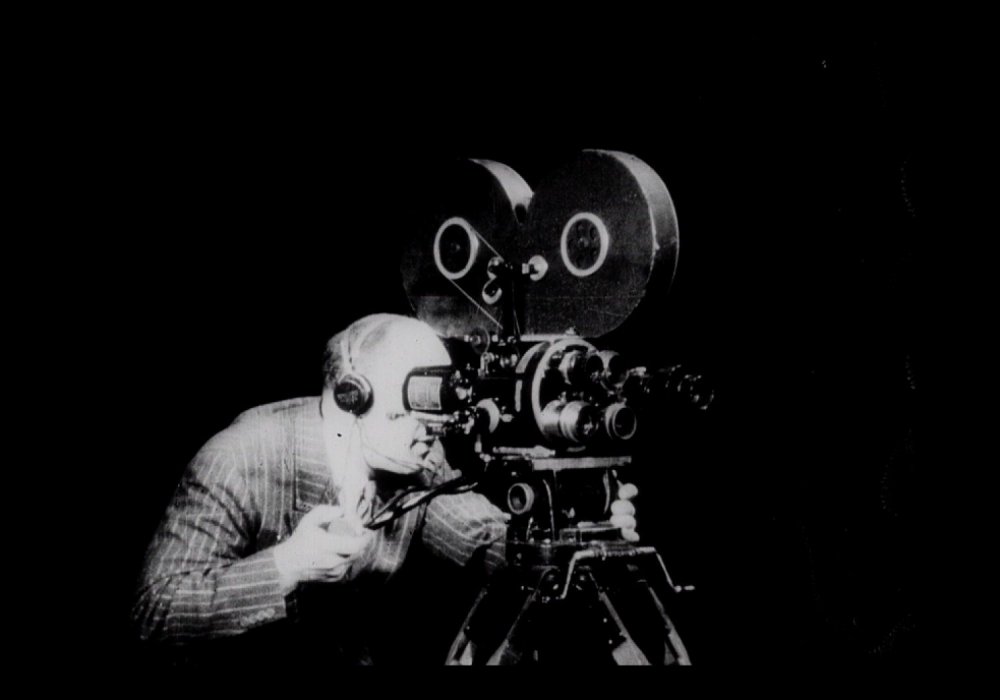

BAFICI’s other competition strands included a variety of attention-catching new local works, such as the minimalist drama Mauro and the musical Living Stars. Two of the festival’s most compelling national films however screened outside of any competition. The first, the omnibus feature Intervened Events (Sucesos Intervenidos), consisted of shorts by a who’s who of Argentine documentary and experimental-film giants, including Cozarinsky and Fontán but also Claudio Caldini, Andrés Di Tella, Gabriela Golder and Hernán Khourian. Each created a piece of a few minutes in length using archival footage from Sucesos Argentinos (Argentine Events), a popular newsreel series from 1938 to 1972 whose episodes have recently begun to be digitised by Buenos Aires’s Pablo C. Ducrós Hicken Film Museum.

Though the filmmakers’ individual styles would have been better showcased with more footage at their disposal, several of the film’s segments still haunt indelibly. Some examples include Di Tella’s chosen slow-motion images of couples dancing (which take on the quality of a resurrected home movie as an older woman’s voice laughs over them), Gabriel Medina’s matches of ghostly echoes to marching soldiers, and Gastón Solnicki’s generation of manic energy through the layering of a Béla Bartók composition over images of children running through snow.

The Colour Out of Space (El color que cayó del cielo)

Intervened Events preserves a series of live acts of processing the past, as does former BAFICI Artistic Director Sergio Wolf’s melancholy and hilarious feature-length documentary The Color Out of Space (El color que cayó del cielo). The film’s main characters are ‘meteor hunters’, a handful of scientists and researchers seeking grounded meteors for whom Wolf searches throughout quick-moving scenes.

Two men in particular emerge game for Wolf’s attentive interviewing. The pensively withdrawn retired geologist William Cassidy preaches caution and responsibility over adventurousness, while his younger former colleague Robert Haag (see meteoriteman.com) bursts with excitement about some of his quests, including one in Argentina 20 years ago.

Haag charms as he recounts his hunt for the large grounded meteor called the ‘Mesón de Fierro’ (Iron Inn), despite local law enforcement’s best efforts to stop him. His stories are illustrated by older photographs showing the areas where they took place, though not the Mesón de Fierro itself, preserved (we’re told) in no audiovisual record.

Then, in a startling moment, we learn from Haag that the contrary might be true. The Color Out of Space exudes constant surprise from everyone involved, building to senses of mutual excitement and relief.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.