At this year’s London Film Festival, a theme of communities and individuals living in more or less isolated conditions were noticeable across the programme of fiction and documentaries, perhaps indicating an interest among filmmakers in lives lived off the digital grid. Dramas such as Stephen Fingleton’s The Survivalist and Tom Geens’ Couple in a Hole looked at characters who have rejected society for reasons of self-preservation, and explored themes of communication, grief and violence. Elsewhere, a variety of approaches to documenting actual struggling populations showed that the consequences of outside help can often be both positive and negative.

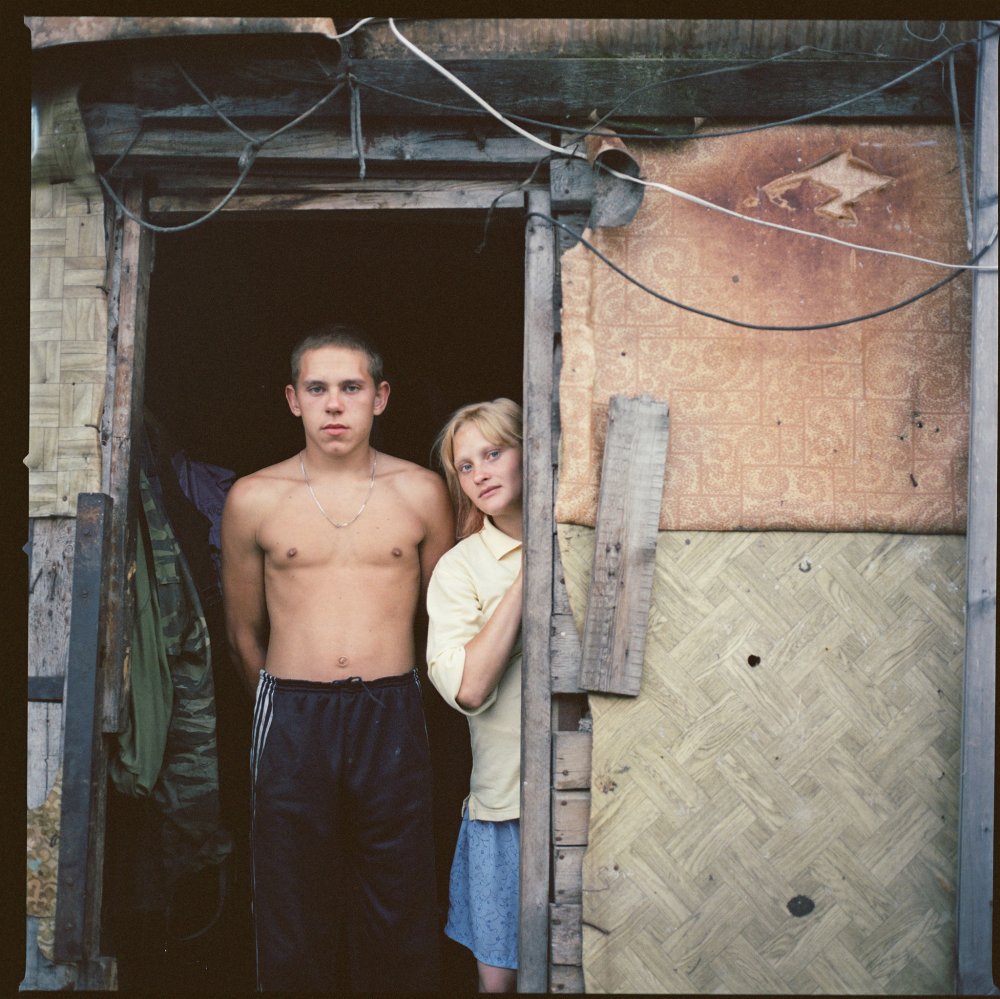

Committing 14 years to her subject, director Hanna Polak was moved to assist in whatever way possible when she discovered people living in the largest junkyard in Europe, known as the Svalka, in Moscow, 13 miles from the Kremlin. The resulting documentary, Something Better to Come, takes its title from a quote by Maxim Gorky (“Everyone, my friend, lives for something better to come”), and looks at the ways adults and children attempt to survive absolute poverty. Polak focuses on Yula who, along with her mother, was evicted from her apartment after her father died and now lives at the Svalka. Introduced at age ten, Yula is shown giving Polak a tour of the cardboard shack she calls her home, and in voiceover declares: “I want a normal life. Not the one I have, which is not even close to normal.”

Something Better to Come (2014)

Over the years we see we see Polak become a welcome presence to the inhabitants of the dump, and an inconvenience to the authorities who are repeatedly shown attempting to stop her filming. Titles indicate the passing of time according to Yula’s advancing years. At 14, a scene at night in the close quarters of her home shows her and her mother drinking ‘unlabelled’ vodka with some friends. One friend challenges Polak (and by implication, the viewer) directly – her camera exposes his troubled life, but could she leave her home comforts to survive as he does? Such raw frustration and directness conveys both the trust built between the director and her subjects, and the tension arising from Polak’s liberties as visitor in a place that traps its permanent residents.

Something Better to Come is remarkable for its commitment to portraying the complexity of the junkyard inhabitants’ lives, and how systematic neglect and learned dependencies prevent the communities that have developed there from moving on. Such systems of oppression were also visible in writer-director Chloé Zhao’s Songs My Brother Taught Me, which takes as its subject the residents of Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Zhao spent four years living and visiting Pine Ridge and the Lakota people who live there, after she read an article about the high suicide rates in the region (over 100 attempted or successful in 2009, numbers that are just as high in 2015). Rather than craft a straight documentary, Zhao instead followed a narrative that would reflect the experiences of those she encountered, incorporating events from their lives throughout the shoot.

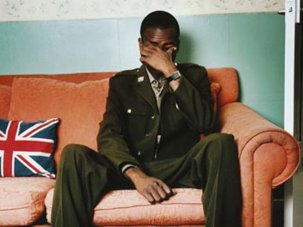

The plot concerns brother and sister Johnny (John Reddy) and Jashaun (Jashaun St. John), who live with their mother Lisa (Irene Bedard). Lisa is shown to be unemployed and suffering from alcohol addiction – a common affliction here. Alcohol is illegal on the reservation, but bootleggers distribute to the many dependent adults and children there, and Zhao’s film shows Johnny slipping into the business too. Whether Johnny will remain a bootlegger, boxer and bull rider in Pine Ridge or escape with his girlfriend Aurelia (Taysha Fuller) to Los Angeles is the question that ostensibly drives the plot forward, but Zhao’s approach is much more impressionistic than such a brief summary suggests.

Songs My Brother Taught Me (2015)

Other characters include Travis (Travis Lone Hill), an illustrator and tattoo artist who sells crafts from his car outside his home, and laments with his buddies the change that occurs in them whenever alcohol is around. Meanwhile Johnny and Jashaun’s older brother Cody, imprisoned for bootlegging, hates Lisa, and is sceptical when she claims to have turned to religion for help (“Just don’t make God another man you abandoned your children for”). Throughout, Zhao keeps her camerawork loose, observing the performances in often tight framing and shooting in a notably Malickian style in mostly natural light. Peter Golub’s mournful score is restrained, punctuating moments of heightened intensity with delicacy, and otherwise allowing natural sound to form the backbone of the film’s aural elements.

Both Something Better to Come and Songs My Brother Taught Me allow their protagonists’ perspective to guide the viewer toward an understanding of their struggle. Where Polak condenses 14 years into 98 minutes, years passing in minutes that show Yula’s developing maturity through her direct testimonial, Zhao’s collective time in Pine Ridge is evident in the compassionate way she creates an atmosphere of home and belonging to the land, despite the suffering each character endures.

Taking a more experimental approach to depicting a community, Olivia Wyatt’s Sailing a Sinking Sea combines non-sync sound and a variety of formats (including Super 8 and GoPro) to provide insight to the lives of the Moken people of Burma and Thailand. Until recently living nomadically around the islands of the Andaman Sea, the Moken survived the 2004 tsunami because their folklore had been predicting it for thousands of years.

Sailing a Sinking Sea (2015)

Wyatt’s film combines stories from the Moken, including fairytales told in voiceover, with footage of the underwater world they inhabit and traditions being passed on. Creating an atmospheric, sensory experience through the distortion of image and sound, she conveys the deep connection the Moken have to nature: “Without the sea, no one on earth could survive – not just the Moken.” Now facing restrictions on movement due to government intervention, the Moken are an example of a community that had thrived in isolation due to their self-sufficiency, and is now in danger of succumbing to the same dependencies as the Lakota, such as alcohol introduced by tourists.

The differing approaches of each filmmaker to their subject seems demonstrable of their intent. Polak’s advancing chapters show with each year the increasing desperation of an unchanging situation – a cry for attention to be paid towards an ignored people. Zhao’s narrativisation of the experience of the Pine Ridge residents speaks to an attempt to elicit an understanding of a community connected deeply to their land, where even the chance to leave seems somehow more threatening than staying put. By creating an immersive, almost tactile cinematic experience, Wyatt’s approach in Sailing a Sinking Sea portrays the essential practicality and beauty of Moken lives lived mostly underwater, advocating for a life free from the cash economy that is slowly creeping in.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.