Web exclusive

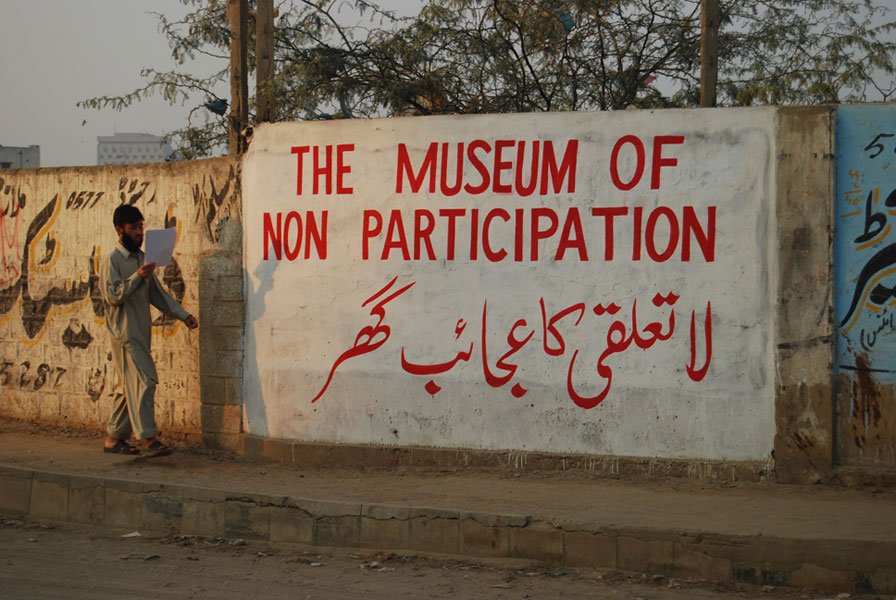

The Museum of Non Participation

“First of all, you’re all going to have to stand up. I’m not going to try to explain. It’s better that we experience it together. We want to open up a festival that has a lot of ventilation to it… a time to reflect.” With these words Barry Esson, co-organiser (with Bryony McIntyre) of Arika, launched ‘A Film is a Statement’, the first of three mini-festival-like ‘episodes’ of experimental film, music and performance to take place in Glasgow in early 2012. Arika has a strong curatorial track record, having previously organised the INSTAL series of music festivals in Glasgow and the Kill Your Timid Notion sound-and-image festivals in Dundee and elsewhere.

Esson’s reluctance to explain, to impose structures on the experience of a work, reflects both the principles of Arika and the adventurousness of its audience. Again and again over the three days (20-22 January) of ‘A Film is a Statement’, Esson, in introducing post-event discussions, went out of his way to make it clear that the person who would lead the discussion was not there in the traditional role of authoritative expert but was simply someone who, having had time to think about a topic, was willing to suggest how the rest of us might get up to speed. Esson also told me of a group of Glaswegians who prepared for the festival by reading and discussing relevant texts. Perhaps this group provided some of the voices that were heard in the often highly sophisticated discussions. Lack of walkouts, even during films that most festivals would consider audience-unfriendly in the extreme, testified to audience interest, and attendance was remarkable: each of the events (most of them held at a gallery space in the Centre for Contemporary Arts) drew, by my estimates, 100 people or more.

What the audience was instructed to stand up for, at the opening event on Friday night, was The Museum of Non Participation, a video-and-performance project conceived by Karen Mirza and Brad Butler in response to the violent state repression of the Lawyers’ Movement in Pakistan in 2007. In this Glasgow incarnation (with the collaboration of Nabil Ahmed), Mirza and Butler read texts, separately or at once, while video images from Pakistan and elsewhere were projected at opposite sides of the room. Making inescapable the choice of where to look at any time, The Museum of Non Participation made the viewer consider if looking has consequences and what they would be. Voices speaking over and speaking for images, viewers not knowing where to place themselves and certain only of the unavailability of an ideal view: these elements of the piece would emerge as themes throughout the weekend.

November (2004)

Two subsequent events were also concerned with driving wedges between the substance of the image and the idealisations of narrative. Philosopher Nina Power’s presentation of Hito Steyerl’s fascinating short film November (2004) focused on how the proliferation of images (of Andrea Wolf, a German internationalist who espoused the Kurdish cause and was murdered in Turkey) entails the loss of content. A video/performance piece by Ayreen Anastas and Rene Gabri called I want to go without you: fiction in the absence of proper names flaunted a certain lack at its origin by returning repeatedly to extended shots of the script pages.

Billed in the catalogue as “recently rediscovered but still pertinent”, Kino Beleške (Film Notes) is a 30-minute film made in Belgrade in 1975. Presumably the pertinence of the film in the Arika context lay in its critique of art-as-self-expression (another recurring theme of the festival). Kept afloat by an austere Godardian playfulness, the film has acquired both historical value and a certain nostalgic tone through its documentation of a little-known underground art scene. One member of this “disorganised group of artists” (as director Lutz Becker, who came for the screening, described them) would achieve fame: performance artist Marina Abramović, seen in one of the film’s characteristic deadpan long takes compulsively combing and recombine her hair while intoning “Art must be beautiful.” The film also contains some charmingly goofy cinephilic moments: a man recounting the plot of King Vidor’s The Crowd while failing to juggle three balls in the air; another man putting on a ‘Montgomery’ raincoat in homage to Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le samurai.

Playfulness is not the strong suit of Arika’s other 70s rediscovery, Anthony McCall and Andrew Tyndall’s Argument (1978), a dour essay in basic media criticism inspired both by Godard and Gorin’s Letter to Jane and Hollis Frampton’s (nostalgia). It was hard, watching Argument, to avoid feeling that this film, even more than Kino Beleške and against the filmmakers’ intentions, is now interesting only because it uses a vocabulary and a tone that have become so dated as to feel quaint. Argument can at least boast of its spoken end-credits sequence, in which a man in profile closeup cites all conceivable entities that contributed directly or indirectly, positively or negatively, to making the film, including the organisations that turned down the filmmakers’ grant applications.

Too Soon, Too Late (1982)

A more welcome revival was Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet’s Too Early, Too Late (Trop tôt, trop hard, 1982), whose lingering astringency pierced the murk of the BFI’s 16mm print and also cut through the haze of an uncharacteristically misguided Arika post-film discussion, at least until the latter was hijacked by a man who denounced the “atrophied formalism” of everyone else who had spoken and sneered at them all for taking part in “this Straub-Huillet Bazinian lovefest.” By then time was about up and we soon were forced, in chastened mood, to abandon the room. One of the problematic aspects of the discussion was the expectation that the Egyptian section of Straub and Huillet’s two-part film should somehow demonstrably connect to the Egyptian revolution of 30 years later, with the implication that the failure to do so was damning for the politics of the film.

The weekend closed with a thud with a video by the Russian collective Chto delat? (‘What is to be done?’). After a long and voluble Skype introduction by one of the members of the group, who promised that we were about to see “a new form of contemporary tragedy” that would reopen the Lukacs-Brecht debates, it was disappointing to encounter in the group’s Songspiels an old-fashioned satirical agitprop opera, performed with monotonous professionalism by a large cast and filmed according to the most starched and trite canned-theatre formulae.

Aluminium: Beauty, Incorruptibility, Lightness and Abundance, the Metal of the Future

Standing apart in radically different ways from the rest of the program were two works by visiting artists. Graham Harwood, who cheerfully introduced himself in a South London accent as “an accidental filmmaker”, generated the eight-minute Aluminium: Beauty, Incorruptibility, Lightness and Abundance, the Metal of the Future (2008) by writing a program that used Internet search-engine results from queries derived from a Futurist manifesto as the basis for altering two industrial films made by the aluminium industry (‘Aluminium on the March’, 1956 and ‘Metal in Harmony, 1962). The striking result materialises cinematic time only to liquefy it, as time subdivides among various forms that mutate across the image track in ways that, in Harwood’s words, show “how the aluminium works its way through us.”

Harwood may be an accidental filmmaker; Hartmut Bitomsky is every inch a filmmaker, and if there is accident in his films, which there is – in B-52 (2001), which he presented in Glasgow, Bitomsky’s on-camera interview subjects are constantly telling him things he clearly hasn’t heard in advance from them – it finds its place within a film form that is excitingly, economically worked through, both in terms of the square, clean 35mm image and in the unsentimental editing. Like the Straub-Huillet film, B-52 (which explores multiple aspects of the history of the USA’s longest-lived bomber) reminded the audience of the existence of a political cinema that knows the need for breathing space.